Ardnacrusha: National Development with Gaelic Character-istics

“It is by no means so easy to forecast the reactions of [Ardnacrusha] upon Irish life as it is lived today. Will it mean in the long run the emergence of a new type of Irishman, alert to apply to his own purpose every modern discovery and every improved method, yet cherishing at the same time the ideals of the legendary past and drawing his mental sustenance from Gaelic culture?. It may be that Gaelic, backed by electrical power, will provide an explosive mixture strong enough to smash the old moulds and radically transform Irish mentality”[1]

Fiat Lux in the Free State

The economic and psychological seeds of Irish globalism were laid in the failure to create a viable decolonised national economy in the early decades of independence.

With the revolutionary potential of a generation splintered into rival camps, with the loadstone of partition, with the morbid drain of emigration, and with dominance of the English market as a roadblock to industrialisation, our fledgling state was left to wither on the proverbial vine of global forces. Reduced to a mere plaything of halfhearted Dublin civil servants, and engrossed faction fighting, the 26 counties fell very far away from the romantic verse of Pearse, the aspirational syndicalism of Connolly, or even the economic assertiveness of Griffith.

Hackneyed as it is, this timeline is not as fatalistic as neoliberal commentators would have us believe. Their version of events ignores the burst of dynamism seen in the early Free State, as well as the positive effect of De Valera’s post-1932 state building, particularly with regards the semi-state sector. The centrepiece for this early magnetism was shown in the Hydroelectric Scheme at Ardnacrusha where the damming of the Shannon River paved the way for the quickfire electrification of the state to the surprise of global commentators.

Born out of the foresight of the high minded engineer Thomas McLaughlin, the parable of Ardnacrusha indicates what even a halfway competent Irish state can do in promoting national self-reliance. Making use of a slight fall of the Shannon near Lough Derg, the scheme was completed between 1925 and 1929 following the cajoling of senior politicians. From the onset Ardnacrusha wasn’t just a standard infrastructure project but a fusionary exploit utilising the best of Gaelic vision with European technical skill.

In short what was to be created was a brand of Gaelic modernism and one which would shoulder a newly liberated people into the 20th century. If Irishmen had asserted their claim to nationality through force of arms, now was the time to forge the economic springboard for that nationhood to flourish against the easy road of economic liberalisation.

Inspired by the post-war recovery efforts of the German state in comparable hydroelectric schemes in Bavaria, the endeavour was sponsored by the Siemens-Schuckert company and led to the eventual birth of the ESB. Chief Engineer to the Irish state McLaughlin first martialled his personal connections with leading members of cabinet (Desmond Fitzgerald and Eoin McNeil) to convince the rather cash strapped state to see the prudence in investing in a viable electrification scheme.

In a nation of damp cottages still watched over by an Anglo-Irish economic oligarchy out of Dublin, such a scheme aimed to shatter notions that Ireland would remain merely a backwater to the modern world.

At the time the Free State was running lower electrification rates than most of war-ravaged Western Europe or even the Orange state. Thus it was judged by McLaughlin that reliance on turf and coal would not be sufficient to safeguard Irish economic advancement. Leading to an tentative White Paper[2] It is unlikely that without McLaughlin’s lobbying the scheme would have transpired at all, given he worked with a state and national leadership more fixated on shooting former comrades and quibbling over the finer constitutional points.

A site upstream on the Liffey was originally conceived as the site for the project, but this notion was eventually ruled out due to size constraints. For McLaughlin it would be the Shannon or bust, and on the River that Fionn mac Cumhaill tasted the Salmon of Knowledge the Irish people would try to enter the modern age on their own terms.

Facing chiding opposition from the Institution of Civil Engineers, agrarian groups, as well as pro-unionist members in the Seanad, the Shannon scheme first broke ground in 1925 regardless of its opposition. In particular, the presence of a German rather than an Anglo-American firm irked pro-British members of the industrial establishment and press[3], such was the colonial hangover among some Irish elites.

Far from being the national state envisioned by Collins[4] when he put pen to paper on the Treaty, or the Catholic theocracy we hear about from RTÉ, the early Free State was still an economic satellite of empire (economic as well as political), with politicians in Leinster House holding on for dear life against the Republican threat. The developers on the Shannon faced a variety of challenges around the project, ranging from industrial disputes, establishing the correct tariff rates, as well as replacing a DC with AC system. Had the planners behaved with the same incompetence as the planners of the National Children’s Hospital have, the early state would have potentially have faced bankruptcy.

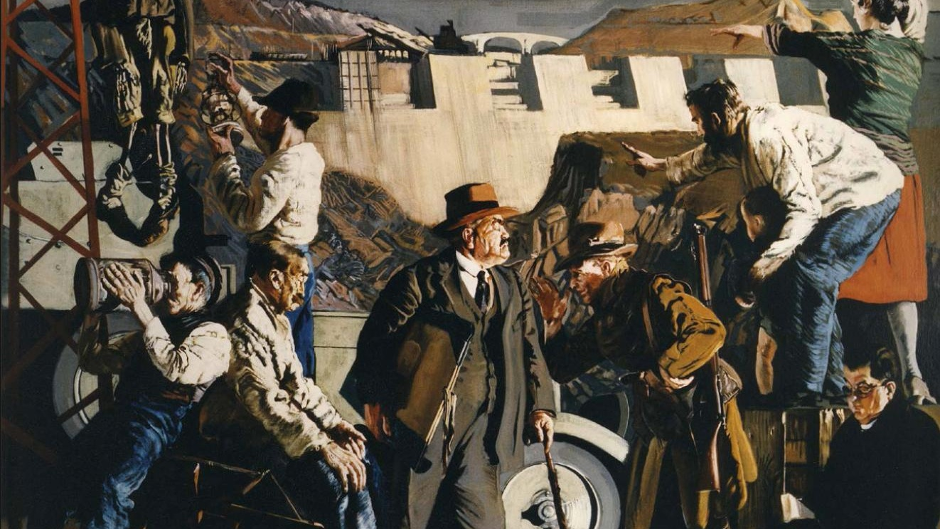

An unlikely feature of the construction was the presence of the painter Sean Keating, whose paintings on the construction typified the larger state-building aesthetic that was occurring at the time. McLaughlin himself features as a sort of Randian hero in a black overcoat in the centre in the now famous ‘When the Candles Are Burnt Out’, a painting meant to represent the modernist thrust of the entire project.

Similar to the new coinage, or the Free State handbook, the early aesthetic of the state indicates the primal yet modern look that was much sought after. An aesthetic that turbocharged the Irish nation into modernity while espousing the same folk prudence which bore the nation in its cradle. Irish economic development was not some statistics game, but an event arising triumphant from an older sense of ethnos which transcended petty ideological squabbles and transient bossman politics.

Assisted by large contingents of German technicians and Connemara labourers, McLaughlin by the end of the scheme found himself installed as the first Managing Director of the ESB.

Today with its turbines still turning, 2% of Irish electrical needs are met by the dam which in subsequent years became a massive propaganda point for the ailing Free State government. For all the failings of the early state they could at least proceed with the knowledge they had a de facto safe power supply and had mitigated the chances of the lights going out on the national project amid a Europe filled with failing states.

Ireland: Globalism When the Lights Go Out

If Ardnacrusha represented a stab at national development, it is downstream from it that we can see an example of the handiwork of Irish neoliberalism at the Aughinish alumina works. Bandied about a variety of foreign owners and currently the private domain of Russian oligarchs, the site has developed a negative reputation for its power use, tax evasion, environmental damage, and general lack of economic worth to the nation beyond a few localised paypackets.

While Ardanacrusha was intended as an intentional loss leader to cater for national electrification, Aughinish typifies the myopic sugar rush of foreign direct investment and the dependency it generates.

While the Irish of the 1920s could be genuinely prideful that their state leapfrogged the world in electrification we ironically face the lights going out over the next decade. Hemmed in by carbon colonialism in the form of Green edicts and the energy demands of a vampiric brand of mordant neoliberalism, Irish capitalism is juggling too many balls to sustain the energy grid for the coming decade.

The geopolitics of Ardnacrusha in particular the turning away from England to Germany shows what an animated Irish state can do if it is brave enough to play larger powers off each other. Imagine if you were an Irish Taoiseach turning down more energy guzzling Amazon data centres in lieu of an agreement with the Chinese or Russians to construct Generation IV nuclear reactors? Ultimately, why must Ireland operate cap in hand to the logic and vicissitudes of international Anglo-Saxon led capitalism? To a system which logically directs us into being a cosmopolitan service economy rather than the economic breadbasket we should be under proper management.

It is likely that such state building efforts like Ardnacrusha gave the Irish state the economic breathing space it needed to avoid being dragged into Churchill’s 1939 war. The recent sublimation of the state into NATO war efforts is in part driven by the interwoven nature of the Irish economy with the fortunes of Western imperialism, and further underlines that true independence occurs only under the rubric of economic freedom.

If the Dutch can boast of polders or the British of the NHS, what can the Irish state gloat about as a consequence of national effort after a century of the green flag flying over state buildings? Ardancrusha was a small change when it came to what the Irish people were and are capable of doing when given the right drive and national Weltanschauung.

Many good faith reactionaries wish to turn away from technological modernity, returning again to a quasi-luddite version of the tried and true ways of faith and fatherland. The end result of this is a half-developed state which can be bowled over by larger liberal and imperial powers. Similarly those on the promethean left envision development by way of eschewing the past and divorcing man from his national character and local soil. The result is communistic abstractionism and Soviet social engineering. It is not a zero sum game and the answer lies at the meeting of the waters between the two. Contra neoliberal pundits, it is their worldview and market mechanism that hobbles true national development, divorcing infrastructure projects from the organic mass of people constituting the Irish nation.

It is high time to switch the table on these economic Pharisees and their smithian truisms, and to display to the world that it is us Old Irelanders who have a better vision of modernity resting closer to our breast. The fight for Irish freedom is not merely reading Peig Sayers in a rain ridden cottage but acting as a beacon for the world in synthesising the best of modernity and tradition. We do not want to dispense with our folkways, but, like Cuchulainn on his chariot, ride them into a future we set the tempo on, one that marches to the rhythm of the Gaelic mind and genius.

Some say that the era of industrial projects has passed, not so with the deglobalising economy in the post-covid era.The Irish state the next decade will be like a Moore Street junkie going cold turkey once the fragile economic ecosystem it created comes tumbling down. List is more relevant than Locke for a small island country with national aspirations, and the Irish must now again begin the trek on a path of national development, tearing up the rotten planks of neoliberalism along the way.

Since the 19th century, liberalism, as it is best represented by the English connection, has marked the gutting of Irish national life. From the well intentioned but doomed petitioning of O’Connell for domestic legislatures, or the tilted stage of laissez-faire neocolonial economics, which assisted the depopulation of the towns and cottages of a mighty Gaelic nation, the game is rigged with liberalism in Ireland.

The Ireland that we dream of today should think long and hard at the lessons and the alternative future presented by the dam builders on the Shannon. Once the lights begin to go out in globalist Ireland, therein lies the crisis which could see the rejuvenation of the national spirit. Ardanacrusa was what the Irish can do with their political hands behind their back and only an entrée to our true potential.

‘It is not to see our country covered with smoking chimneys and factories. It is not to show a great national balance-sheet, nor to point to a people producing wealth with the self-obliteration of a hive of bees. The real riches of the Irish nation will be the men and women of the Irish nation, the extent to which they are rich in body and mind and character”

[1] The New York Times Magazine, 12/1/1930

[2] The electrification of the Irish Free State : the Shannon Scheme developed by Siemens-Schuckert Oireachtas Historical Collections

[3] The Shannon Scheme and the Electrification of the Free State: Andy Bielenberg 2002

[4] Path to Freedom; Building Up Ireland Michael Collins 1922