A Brief History of the British Subversion of Irish Resistance Movements

The following first appeared on the Substack ‘Creeve Rua’ and is syndicated with the permission of the author.

‘Now I am dying, my body all holes

I think of those traitors who bargained and sold

I'm sorry my rifle has not done the same

For the Quislings who sold out the patriot game’ - The Patriot Game.

The eternal struggle against British meddling

From false alliances and deceptive treaties to intentional sabotage and false flags, Britain’s (continuing) occupation of Ireland has always required the subverting of Irish resistance movements. This article is simply a brief refresher of the numerous times Britain has used its extensive web of subversive tactics to mislead and dislodge burgeoning nationalist sentiment in this land.

While it is important to not slip into paranoia and despondency — where one accuses every instance of effective Irish resistance of being under British control due to cowardice or personal animus against those involved — it is instrumental that younger or newer Irish-Irelanders and Gaelic dissidents are aware of the threat, tactical idiocy and the fundamental betrayal of our ancestors and patriot dead it would to ever collaborate or unite with British interlopers.

While there is always room for dialogue, negotiation and respecting points of agreement, we must say we shall never sully our flag and our ancestor’s name by allying with our people’s most eternal enemy — Never!

Subversion and the Anglo-Normans

Right at the inception of the British occupation of this country, the Normans conquered through subversion — particularly by way of exploiting the narrow-minded intentions of Diarmaid Mac Murchadha.

As a perfectly indicative figure of the original seonín, Mac Murchadha felt that his alliance with Strongbow, through the marriage of his daughter Aoife, was a tactical arrangement based on the ‘enemy of my enemy is friend’ logic. It is undeniable that Mac Murchadha had logical short-term motivations for marching with apparent national foes. He was a great Irish patriot and Lord, and his Uí Ceinnselaig (Kinsella) clan had been humiliated by the ard-rí Toirdhealbhach Mór, of the Ó Conchobhair (O’Connor) house. Considering the foreign Lochlannaigh (Vikings) had already been replacing Irish lords — why not march with the British to reclaim Irish land? — thought Mac Murchadha.

Unfortunately, the small issue with this short-term thinking is that it was perhaps the instrumental event which insured the past near-millennium of continued British occupation of (at least) some part of this country. With the arrival of Strongbow, his troops and merchant’s money into this country, our sovereignty became a property dispute between Mac Murchadha's new military allies -- so much so that the British King was forced to supplant his will over his underlings.

After the insuing struggle, the Normans came to the Treaty of Windsor, which established the now age-old British tradition of deception through false promises. Insuring the Gaels a significant cease in the occupation of the country, gullible Irish leaders trusted their word and signed the treaty — only to be shocked by the total betrayal of its terms by the Anglo-Norman elite. With Mac Murchadha dying several years into this occupation, one wondered if he regretted his ‘strategic union'.

A continuing theme in Irish history, that of the false and unfaithful peace treaty by the British, it also mirrors the assurances and promises the British made to the Arabs of Palestine in more recent years — only to renege on these and wholly transfer the land over to the Zionist militias.

Divide and conquer during the plantations

Following on into the early modern period, the British tactic of stoking division and disloyalty in the Irish resistance really came to the fore. With the Bolshevik-style reorientation of English society through the Reformation, a grand bureaucracy of intelligence and espionage was required to surveil, control and subvert the mostly Catholic English peasantry. Led by Francis Walshingham, Francis Bacon among others, the British mastered the art of winning wars and establishing power by psychological deception. A practice which was naturally applied to suppress and distort the potential for Irish resistance during the plantations.

Really coming to the fore with the Nine Years' War (1594-1603), the British realised the necessity of employing psychological subversion with the Gaelic alliance of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O'Donnell, of Tyrconnell. With the marriage of Róisín Dubh to Tyrconnell, immortalised in the eponymous amhrán, the stage was set for a revitalised Gaelic Caesarism, striking panic and the urgent need for British solutions.

Led by Sir Henry Bagenal, but truly masterminded by the master of subversion, Sir Robert Cecil, the occupying regime promoted a mass propaganda campaign of deception, spreading false information and alliances to divide the recently united Gaels. Offering vast pardons and assurances, many fell to the pressure, most famously Niall Garve O'Donnell. By the Treaty of Mellifont, the rebellion was crushed and the Gaels were divided by way of those who marched with our enemy.

The Irish Confederate wars of the 1640s saw a continuation of this tactic, most strikingly in the case of the originally norman Butler family. While the Owen Roe O'Neill-led Papal alliance was built on potentially unstable conditions, the old-English and protestant contingents were particularly vulnerable to subversion. With James Butler and the House of Ormond, their supposed insecurity in southern Leinster meant that negotatiang and confiding in both Royalists and Parliamentarians was the only strategic approach feasible.

Despite this cleverness, their betrayal of the Irish nation not only contributed to the supremacy of Cromwellian expansion, but also to the eventual collapse of the Butler's own property of Cill Chais (the basis of another classic sean nós tune). Much like Mac Murchadha, the Butler's ‘savvy’ open-mindedness betrayed the Irish nation for nothing.

The infiltration of the Fenians

Entering the radical Fenian period of the late 18th and 19th centuries, successive British governments began to more successively, in part due to to the increasing influence of the English language, employ explicitly recognisable forms of infiltration, with the use of informers, plants and spies.

These skills were naturally harnessed by the implementation of the Penal Laws, where priest hunters would infiltrate and surveil underground Catholic worshippers, in a eerily similar sense to the Red Terror or Maoist struggle sessions of yesteryear, creating a surveillance state to rout out those loyal to the ‘counter-revolutionary' traditional faith of Christendom.

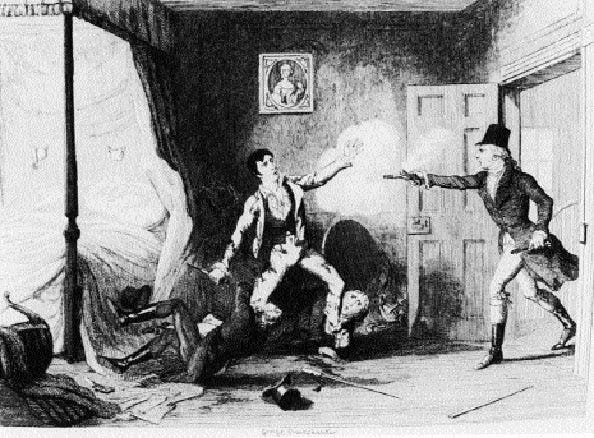

Beyond this, the Fenian era allowed the British to employ rather direct espionage with the English-speaking revolutionaries of the post-Enlightenment. The most prominent example would of course be Thomas Reynolds, who betrayed the mostly Protestant revolutionaries of the United Irishmen. Into the 19th Century, the name of Pierce Nagle is similar yet less known example which reminds one of those who nformed on and betrayed the Fenian movement at the peak of British exploitation.

The use of shock and scandal was certainly applied in various instances, in a way to curtail the momentum of agrarian movements, particularly during the land war with the case of Charles Stewart Parnell. An educated Protestant, with close ties to English radicals and Whigs, Parnell must have seemed to be a supremely effective bludgeon for the Gaelic Catholic majority. He even seemed to appeal to and persuade the British prime minister, Gladstone. With all of these English connections, the three ‘F’s and Home Rule must have appeared to have serious political potential.

But all that clout and respectability vanished once an embarrassing scandal about Parnell’s infidelity was revealed to the British press — proving all the English alliances in the world are meaningless once a personal crisis develops.

False promises in the Revolutionary Period

While not mirroring the explicitly subversive activity of previous generations so much, the revolutionary period also contained numerous instances of false British promises, and attempts to neuter the National movement from its radical form to be yet another instrument of Anglicised control.

One classic case of this is that of the contingent led by John Redmond, who sincerely believed the British’ promises of Home Rule would be fulfilled so long as tens of thousands of Irishmen died in the service of the British Empire’s colonial ambitions in World War 1.

The famous woodenbridge speech of Redmond echoes out into the historical memory of the Gael, everytime an Irish man or woman comes to think that we should ally with our ancient enemy. It echoes, as a very similar speech at the same period of time, at the funeral of the great patriot O'Donovan Rossa, suggests an alternative philosophy toward marching in the subservience and comradeship of those who subvert and sabotage our independence every generation.

It could be said, that we may never fully know what would have come of their promise, due to the stubbornness of a minority of Volunteers in the IRB during one fateful Easter Week. However, based on the track record of British alliances and promises over the years, I believe one would have to be remarkably intransigent to the wisdom of our forefathers to think marching and dying under subservience to those who hate us would lead to any greater independence.

When one ponders the many well-intentioned Irishmen who went out to die under the flag of their occupation, in order to establish some imagined independence, the tremendous sense of tragedy is palpable. More than melancholy however, is the righteous indignation toward those who sullied the image of the many well-intentioned Irish men women who fought and dreamt of a Gaelic and Free country.

The necessity of Irish nationalism being Irish

Whether it be in the case of the dangerous naivety of Mac Murchadha and Redmond, or the treacherous cowardice of Garve O'Donnell and Thomas Reynolds -- it is paramount that the cause of Ireland is fully independent from the corrosive influence of British subversion. Every successful movement will have its infultrators, subversives, naive fools - the history of Republicanism assures one of that - but it is paramount that the intellectual rearguard of any movement clearly delineate the atrocity of encouraging collaboration with one's ancient historic enemy. It has been tried before, it will be tried again, and it has never and will never end in anything but the miserable setting back of Irish independence. Never!