A History of Ireland in a Church Door [Part 1]

An important architectural feat of the Romans was the mastering of the Arch. In the evolution of Irish Church doorways, you can see their design started as a Trabeate (post and lintel) - basically a flat horizontal doorway. [See the Trabeate doorway which has a Greek cross carved in - said to have been raised by St Féchín's prayers.] You can see this in the likes of Stonehenge (an example of Neolithic post & lintel construction) or the Parthenon in ancient Greece - the Greeks mastering the art of the Column which are essentially more refined Posts the hold up the horizontal Lintel (the Greeks always refining this with beautiful artwork etc).

Before the Romans, other civilizations particularly in Mesopotamia had used Arches in construction, but only for drainage systems and rarely for outdoor buildings. The ancient Romans learned the arch from the Etruscans and refined it. The Romans then became the first builders in Europe, perhaps the first in the world, to fully appreciate the advantages of the Arch, the Vault and the Dome. If you look at a Roman Aqueducts - its just a repeated series of Arches. Roman arched bridges from 150 BC still stand today.

If we put ourselves in the shoes of someone living in 500+ BC - the idea of forming stone into an incredibly large archway for a building or bridge probably seemed like magic. There were attempts at it but only on small scales as noted above (drainages etc). It must have seemed impossible. Timber and such made sense since material can be light enough, but incredibly heavy stone?

However when one looks at nature, for example the Green Bridge of Wales or Pont d'Arc in France - Nature shows us examples that such arches are possible. If I were to guess, they must have been inspired seeing formations like this in nature and made it reality.

When studying architecture of Europe, it’s important to remember that Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia were never conquered by the Romans. Thus, a lot of stone building techniques were never imported until much later. So a lot of native architecture in non-Roman parts involved some stone but the vast majority was wood/timber. Irish stone structures did exist like the Portal Dolmens, Newgrange, Dún Aonghasa etc. However, stone building didn't kick in extensively until Christianity arrived, as is the case in Scandinavia too. Christianity brought more contact with the Continent, and with Irish missionaries and pilgrims going to Europe, ideas came back and we saw stone Churches popping up in the 500-700s.

In Ireland, the 6th century had been the heroic age of the monasteries, the time of the great founders whose names were afterwards held in reverence by the Early Christian Irish, but the art/architecture remained native and simple. This was the time for the early Irish Saints Christianizing Ireland like the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. To judge the surviving material remains, the monastic culture of the period, in rudeness and simplicity, reflected the monastic ideal of living a simple life, embracing pure asceticism - Green Martyrdom (glasmartre). Scelig Michael and the Beehive huts are examples.

But when the 7th century was well advanced, when the monasteries had grown in size and wealth, the demand arose for liturgical vessels, for reliquaries, for Gospel books fit to grace the altar. It was then that suddenly a mature and masterly art style, based on supreme excellence of craftsmanship, in book painting, in metal and enamel working, and in stone carving, came into being to meet the demand. This is where we see more advanced early High Crosses, The Book of Durrow, Ardagh Chalice etc.

Ireland can be quite unique in Western Europe during this period for the stone structures it produced as they were of a pure native and non-Roman design. They were simple but again fairly alien to what one would see elsewhere in Europe - example being the Irish round towers. This period is normally referred to as the Golden Age of Irish monasticism and was also met with the numerous missions around Europe during the Heroic Age of Irish Missionaries.

The Vikings appearing in the late 9th century began to disrupt this artistic and architectural expansion of the Irish. Irish High King Brian Boru stated it best in his speech at Clontarf in 1014:

“They have razed our proudest castles — spoiled the Temples of the Lord — Burned to dust the sacred relics — put the Peaceful to the sword — Desecrated all things holy — as they soon may do again, If their power to-day we smite not — if to-day we be not men!”

Once the Viking Wars were over after King Boru's victory at Clontarf, kings competing for the High Kingship commissioned more Church building and artwork to stamp their legacy and legitimacy for High Kingship. Boru himself had already at the turn of the 11th Century begun building Churches along the Shannon, which was used as a highway for the Viking marauders who he had just tamed. These Churches slowly began to take more rounded arches on their doorways, instead of the simple lintel in early Churches.

St. Cronan’s Church, Tuamgraney, Co. Clare, built in 980s under King Brian Boru, is a good example of this. The outside door is an adaptation to the previous doors seen in early Churches, with a better shaped lintel made of more refined stone rather than piles of stones stacked on one another, while inside the Church there is a basic arch splitting the nave from the chancel. Chancels also started appearing in this 10-11th century period in Irish Church architecture.

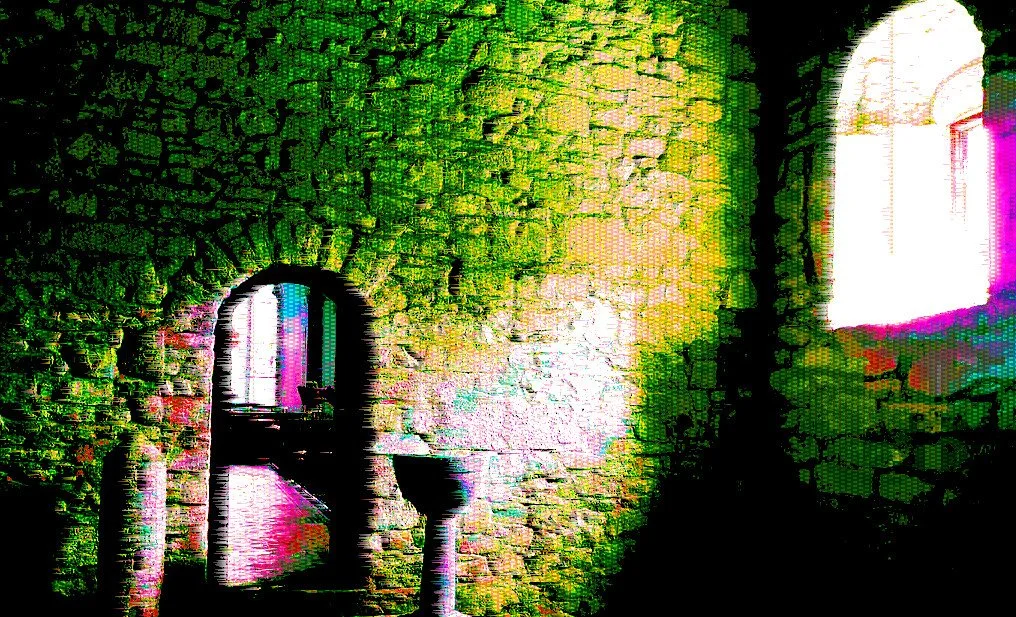

As we advance into the 11th Century, we get more of these additions with examples being Trinity Church and Reefert Church, both in Glendalough. Again, they are simple nave and chancel churches with round arches splitting the nave from chancel.

You can see what I'm getting at — the Gael is learning to appreciate the Arch — just like the Roman. The Gael went from a basic Post and Lintel and is now adding the Arch to stone buildings.

In Europe between the 6th - 11th Century, this process was ongoing in the emerging Christian nations — the style being referred to as 'Romanesque'. Essentially, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a lot of the techniques in stone building were lost due to the chaos of the times. But the Roman structures remained. This led people to try and imitate what the Romans had built. This resulted in all sorts of native degenerations of the original architecture as they didn't fully understand how to imitate the Romans.

This is why people try to refer to this time as a Dark Age, but really it ended up being an age of native innovation. We get all sorts of styles in this period with each emerging nation producing their own blends on the Roman style - hence the term 'Romanesque'.

At the turn of the 12th Century, we start seeing more of this Romanesque influence. St Flannan's Oratory (c. 1100 AD) is the first example which shows the first signs of the Romanesque style which was spread around the continent. You can see the Door has a lot more detail looking like a portal. Being the earliest surviving example of a Romanesque doorway in Ireland, so a first of its kind, it is a very basic example of the style. As will be discussed next, this will soon be greatly expanded upon, blending with the native Gael mind to form a Hiberno-Romanesque style.

This was the same period stone Church building entered Scandinavian countries like Norway, where it was introduced there under the influence of Norman/Anglo-Saxon missionaries, particularly bishop Nicholas Breakspear (Pope Adrian IV, 1100 - 1159) - these places were just reaching full Christianisation around this point. Stone Churches entered Norway mostly during this Romanesque phase in the 12th Century. Before this they normally built stave/log Churches. These wooden stave/log Norwegian Churches & other ones in Scandinavia are beautiful in their own right, but before this there isn't a Non-Roman influenced Native Stone Church building as seen with Ireland.

Scandinavia was warped sped to straight to the contemporary continental style of architecture via Norman-Anglo missionaries, whereas Ireland had a varying evolution over time for its stone Churches that had no Roman input before adopting continental styles.

Before we continue into 12th Century Irish Architecture & see the emergence of Hiberno-Romanesque styles, it's important to delve into the political and social landscape of 12th Century Ireland as there are many misconceptions - thanks to the Norman invasion of 1169 & the propaganda spewed by the likes of Giraldus Cambrensis.

The organisation of Churches in Ireland in the 11th Century were still the same as those in the 7th Century - mostly run under the Rule of Saint Columbanus. However, in the Continent they had been under run under Benedictine monastic rule since Charlemagne in the 800s (Charlemagne had to choose between Columban or Benedictine for a standard and choose the latter).

This is why you see stuff on Ireland 'not being part of the Roman Church' - which isn't true. They saw Rome as the Holy See but followed a different monastic system that was laid out by Irish Saint Columbanus - many places in Europe still had or maintained remnants of Columban rule due to Irish missionaries (St Columbanus is buried in Bobbio, Italy)

In Ireland too, there was a blend of the monastic rule with society. The monasteries at this point in the 11th century were rich. The rule & land was administered by ancient customs (Brehon Law) as well as being ruled by the Comharba (successors) of the founders, i.e control of the monasteries was hereditary.

In Ireland during the Viking wars, a few ethnic changes occurred. There were now Hiberno-Norse communities in Limerick, Waterford and Dublin. Because these families could never be Comharba, it meant they could never gain control of monasteries as monastic rule via Comharba was only transmitted by natural or nepotic descent within ecclesiastical families, which were often the politically displaced branches of royal Gaelic dynasties. This led to these Hiberno-Norse communities to begin sending their Bishops to be consecrated in Canterbury. Dublin first sent their Bishops there followed by Waterford and Limerick — we can now see where this is leading.

Let's now look at England in this period.

A reminder that Canterbury post-1066 was under Norman control as the Normans conquered Anglo-Saxon England and filled up their elite and ecclesiastical classes with Normans. Some of the Anglo-Saxon nobility like King Harold Godwinson's family had even taken refuge in Ireland to use it as a base to retake England (lol...repeats with Jacobites eh?). Harold's sons, who had taken refuge in Ireland, raided Somerset, Devon and Cornwall from the sea. Harold's sons launched a second raid from Ireland and were defeated at the Battle of Northam in Devon by Norman forces

The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the Byzantine Empire, with many joining the Varangian Guardsmen where Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus is meant to have given them land known as 'New England'.

The Anglo-Saxons at this time had their own 'Flight of the Earls' in 1075, known has the 'Revolt of the Earls', which was the last serious act of resistance against William in the Norman Conquest. William the Conqueror, due to the bloodshed he had brought upon the Christian Anglo-Saxon peoples, requested that his coffin be placed under the eaves of a chapel so that “the drippings of the rain from the roof may wash my bones as I lie and cleanse them from the impurity contracted in my sinful and negligent life.”

Returning to late 1000s Ireland — specifically when these Hiberno-Norse Bishops began to flock over to Canterbury to be consecrated — the Archbishop of Canterbury now took more of an interest in the Irish Church, even claiming jurisdiction over it. In 1093 and 1103, St Anselm of Canterbury wrote to Muirchertach Ua Briain, King of Munster and High King of Ireland from 1101. St Anselm addressed him as 'Glorious King of Ireland' urging him to reform Church affairs with the following abuses listed:

— dissolution of marriages

— irregular consecration of Bishops

— consecration of Bishops without fixed sees ( no Diocese system)

—

As a side note on the dissolution of marriages — this one point is almost seen as a full justification for the Norman invasion (as I'll get into later) but it wasn't an issue unique to Ireland. Many families before the Gregorian Reforms were abusing marriage laws, mostly royal dynasties, and as we're about to see, this issue was being addressed in Ireland as early as 1103 —- over 60 years before the Norman invasion in 1169.

A reminder of it was that St Columbanus was involved in a marriage dispute with members of the Burgundian dynasty. Theuderic II King of Burgundy "very often visited" Columbanus, but when Columbanus rebuked him for having a concubine, the Burgundian dynasty including Brunhilda of Austrasia incited the court & Catholic bishops against Columbanus. Theuderic II confronted Columbanus at Luxeuil, accusing him of violating the "common customs" and "not allowing all Christians" in the monastery. Columbanus asserted his independence to run the monastery without interference and was imprisoned at Besançon for execution.

St Columbanus escaped and returned to Luxeuil. When the king and his grandmother found out, they sent soldiers to drive him back to Ireland by force, separating him from his monks by insisting that only those from Ireland could accompany him into exile. Columbanus was taken to Nevers, then travelled by boat down the Loire river to the coast. At Tours he visited the tomb of Martin of Tours, and sent a message to Theuderic II indicating that within three years he and his children would perish. He found sanctuary with Chlothar II, King of Franks at Soissons, who gave him an escort to the court of King Theudebert II of Austrasia. War then broke out between King Theudebert II and King Theuderic II, with Theuderic winning and murdering Columbanus' students in the woods, and with Columbanus then deciding to cross the Alps into Lombardy.

This is an example of the of the seriousness the question of marriage could invoke in the mediaeval world.

—

In 12th Century Ireland High King Muirchertach Ua Briain was at constant war and under threat of a Norwegian invasion. Let's set the scene:

The Irish had removed Viking influence from Ireland with Clontarf in 1014, and from Irish seas fully by 1052. High King Diarmait mac Máel na mBó (died 1072) who was the King of Leinster also became King of the Isles — the Isles being the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the Western Isles around Scotland. Later, High King Muirchertach Ua Briain strengthened this tie to the isles via political marriage into Manx Royalty, who had requested a king from the Irish royal bloodline. This attracted the attention of the King of Norway, Magnus III, better known as Magnus Barefoot, who wanted to retain Norwegian power. With a fleet of around sixty ships and several thousand men, he re-established Norse power in the area, garrisoning the islands of Orkney and Man.

Magnus then attempted an invasion of Ireland, however his ships were sunk by the Ulaid (who were under Muirchertach's overlordship). Magnus then planned a full assault on Ireland, but the Irish gathered a large army on the coast, and Magnus did not attack. Around this time too, Muirchertach had sent a fleet to Wales to help the Welsh fight the Normans, who were encroaching on their territory on the island of Anglesey. However, the Normans were able to buy off the Irish ships to their side, and the Welsh were defeated.

The English victory celebrations were interrupted by Magnus, however, who landed and routed the Norman army, reputedly shooting Hugh de Montgomery (brother of Arnulf de Montgomery) through the eye, before capturing the island of Anglesey for themselves. Later, when the Irish fleet returned home, they were punished by Muirchertach for their treachery.

Much like his great-grandfather Brian Boru, Muirchertach Ua Briain's High Kingship was continually contested by the Kingdoms of Ulaid and the Northern Uí Néill. Around the same time Magnus Barefoot of Norway had returned with a larger force than his first, possibly with the intention of invading Ireland. Magnus had earlier raided Inis Cathaigh (Scattery Island) at the Shannon estuary in 1101, possibly testing the situation and defences of Ireland.

Muirchertach negotiated with Magnus and agreed to marry his daughter Bjaðmunjo (or Blathmuine), to Magnus's son, Sigurd (the first European king to personally participate in a crusade) in exchange for Magnus's aid in his campaign against Ulster. Muirchertach also recognised Norwegian control over Dublin and Fingal, with the western lands of the Kingdom of Norway under the control of Sigurd, who was announced as co-king alongside Magnus on the day of his wedding.

Muirchertach and Magnus campaigned together in Ulster throughout late 1102 and early the next year. Contrary to the Norse sagas, the Irish Annals describe the campaigns as largely unsuccessful. Not long into this alliance, with the campaigns against Ulster being unsuccessful, Muirchertach wanted the alliance off. Norwegian sources say Muirchertach was supposed to bring Magnus provisions for his return to Norway. When Muirchertach did not show up at the agreed time, Magnus became suspicious the Irish were going to attack. On 24 August 1103, St. Bartholomew's Day — or the day before, according to one source — Magnus gathered his army & landed on the coast of northeastern Ireland. As Magnus landed on the shore, a large Irish force emerged from the thick bush. In the ensuing battle, Magnus was killed, & the Norwegian force was destroyed. His son Sigurd returned to Ireland without his Irish wife Bjaðmunjo & Norwegian influence was removed from the isles for 150 years until the Norwegian-Scottish Wars of 1266.

Following the death of Magnus Barefoot in 1103 and the withdrawal of Norwegian military forces from the Irish Sea area, Muirchertach successfully resumed his attempts to expand Irish power in the region at the expense of the Norse. He was able to re-install his nephew Diarmuit as King of the Isle of Man in the year 1111. With direct control of the Isle of Man, he also exercised control over the other Islands close to the Scottish mainland. At the time, Scotland was ruled by King Edgar . In 1105, Muirchertach received the gift of a camel from Edgar. Some say it was an elephant too.

However it was another challenge which approached Muirchertach's reign — during this time of war with the Norwegians, campaigns in Ulster, and aiding the Welsh against the Normans — which was to be his undoing.