An Appeal for a Gaelic Academy

Word count: 5,950 words

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

Summary: Dr. Kuno Meyer’s 1904 lecture urges the creation of a Gaelic National Academy in Dublin, inspired by Hungary’s language revival. He highlights Hungary’s success in standardising language, fostering literature, and restoring national identity. Meyer believes Ireland must adopt a similar scholarly approach to preserve and revitalise the Irish language.

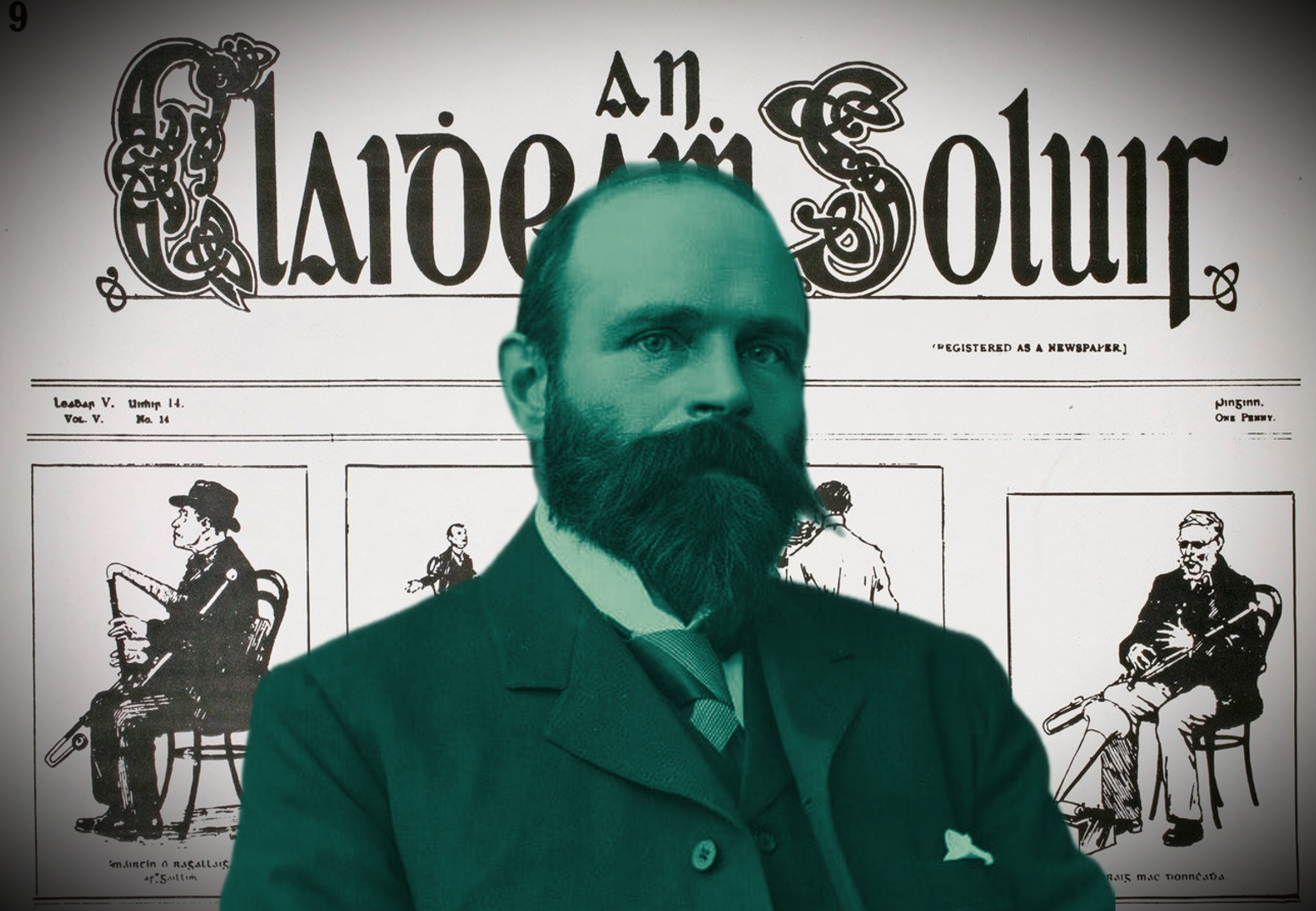

The following lecture was given by Dr. Kuno Meyer in Liverpool, on October 26th, 1904. Dr. Meyer was a renowned German scholar of Celtic studies and an active participant in the Gaelic Revival. This lecture was serialised in An Claidheamh Soluis from the 3rd to the 31st of December 1904. The full lecture has been transcribed and annotated for modern readership.

Note that spelling and punctuation have been altered where required for contemporary publication. In particular, Hungarian town and people names have been reverted to their original form. For example, “Alexander Petofi” has been rendered in this publication as “Sándor Petőfi.” The lecture has separately been titled “The Need for an Irish Academy” or “A Plea for a Gaelic Academy”, in other writings or serialisations. The lecture appears here under its original title “An Appeal for a Gaelic Academy.”

For further research into the Hungarian authors referred to in Dr. Meyer’s lecture, readers are recommended this index.

An Appeal for a Gaelic Academy

Being an Address delivered to the Liverpool Branch of the Gaelic League on October 26th, 1904.

When I received the invitation of your Committee to deliver an address before this branch of the Gaelic League, I happened to find myself in Eastern Europe in a country which has often been compared to Ireland, and has sometimes been held up to her as a model and example to follow—the Kingdom of Hungary. Indeed, the fate of the two countries has been in many respects so similar that the student of their history or the traveller visiting them is constantly reminded by one of the other. Nor can it be denied that the victorious struggle of the Hungarians for their national existence affords many lessons which may usefully serve the cause of an Irish Ireland. A series of brilliantly written and instructive articles on the recent history of Hungary in the columns of the United Irishman has but lately drawn the attention of its readers to the subject. These articles dwelt almost exclusively on the political aspect of the development of Hungary, and drew numerous parallels between Hungarian history and Irish politics. As a student of languages and as one who wishes well to the Gaelic movement, I was even more interested in the story of the revival of the Hungarian language and literature; and during a stay of several months I began to study the history of that movement, and to note the various steps and stages which led to the rehabilitation of Magyar, or Hungarian, as the national language of the country in which I found myself.

Here again comparisons with the Gaelic movement forced themselves upon me at every turn. The more I read and the more I saw and heard what was going on around me, the more I became convinced that the successful career of Hungary contained some fruitful lessons for the Irish to follow, lessons at no moment perhaps more opportune than at the present. So when your summons came, it seemed to me I could hardly do better than to put together some of the facts which I had learnt and to point out their bearing upon the future of the Irish language and literature. In laying these remarks before you tonight, I desire most earnestly to promote the cause of the Gaelic movement which, from its inception, has had my heartfelt sympathy, and, so far as I have been enabled to give it, my co-operation.

Of course, in the short time at my disposal, I cannot give you more than a rapid and meagre sketch. It would be a most useful task if one thoroughly acquainted with the present state and the needs of the Gaelic movement were to find leisure and opportunity to study the Hungarian revival on the spot, and to report on it to the League.

One of the first things that struck me in studying the history of the national development of Hungary was the remarkable fact that the language movement has preceded by half a century the political struggle which brought about autonomy. It seems as if the Hungarian people had first intended to establish their claim to be considered “a nation once again.” It was a period of preparation of rallying their strength and forces, a period during which they became thoroughly imbued with the national idea, while in the process they acquired that unity and solidity, that fusion of hitherto discordant elements which, when the great struggle for national independence arrived, found them united to a man and ready for any sacrifice.

The eighteenth century saw the deepest decay of the national spirit in Hungary. The nation which had so often victoriously withstood foreign invaders had lost its independence under Austrian rule. A process of Germanisation was going on apace in all departments of national life. A generation had grown up in degeneracy brought about by apathy or despair. It had allowed the language and literature to decay, so that for a time a revival seemed almost as hopeless as it did in Ireland a few years ago. Yet the situation was not quite the same as in Ireland before the Gaelic League began its work. In some aspects it was perhaps worse, but in others far better. While the Irish language, e.g., has always had one rival only, viz., English, Hungarian had three, German, French, and Latin. On the whole, this proved to be an advantage when Hungarian began to assert itself, for none of the three languages had obtained such firm root on the soil of Hungary as English had obtained in Ireland, and the enemy’s forces, so to speak, were divided, and could be the more easily attacked and beaten separately.

By the middle of the eighteenth century the neglect of Hungarian as a spoken language had reached its lowest level. It had fallen into general disuse among the upper classes, and all those who laid claim to education and culture. Left to the lower orders, it threatened to degenerate into a mere patois. Latin was the language used in the schools, in all public business, and in the county courts, while German or French had become the language of the home, society at large, and of the stage. There was no living literature in Hungarian, so that in 1764 the patriotic Jesuit, Illei, could write: “Our language has indeed been carried to its grave, though it is not yet wholly dead.” (1)

In spite, however, of this almost general neglect, Hungarian has never come so near extinction as Irish had through such successive calamities as the settlement of foreigners throughout the country, the dispossession of the native land owners, the penal laws, the famine, and the constant drain of emigration. In Hungary, the upper classes, though they disdained to employ their native language, could yet understand it, much as Frederick the Great could speak and write German after a barbarous fashion, though he preferred to use French.

On the whole, then, the difficulties of reviving the language were not nearly so great as they are in Ireland at present.

The first indications of a coming change are found towards the end of the eighteenth century. A reaction set in which first showed itself in the homes and private life of patriotic citizens of all classes, more especially among the nobility, students, and the priesthood, a number of whom began once more to cultivate the native language. There was in this no political object. These men were simply filled with shame and regret that such a fine language should sink to the level of a mere spoke jargon and be left to die out in a few generations.

They realised that Hungarian had all the possibilities of becoming the medium and vehicle of a great modern literature, as it had already in the past produced some fine prose and poetry. But to achieve this the language had first to be cultivated, and many branches of literary expression had to be created. Its claim to be considered one of the civilised languages of Europe had first to be made good. Here indeed their task was much more difficult than that which lies before the Gaelic League. You know that the Hungarian language was a late arrival among the great civilised languages of Europe, with which it was not connected.

No written records exist of it before the 12th century (a time when the Irish language and literature had already had their golden age). It swarmed with foreign words mostly taken from Latin, German, or the surrounding Slavonic languages, which threatened to choke the native element more and more. So little was Hungarian as it then stood adapted to be used, e.g., for purposes of scientific expression in writing or teaching, that as late as 1847 physics, logic, astronomy, and most other sciences had to be taught in the schools through the medium of Latin. But the men who started the movement did not lose heart. They knew that other national languages also had been in the same state, and had equally to fight their way against Latin and other foreign tongues. Had not the development of German been delayed for centuries by the predominance first of Latin, then of French? Why should it not be possible to do in a small country like Hungary what had been done throughout the length and breath of a huge country like Germany, with its numberless dialects, its Universities, and learned men biased in favour of Latin, its courts and society equally prejudiced for French language and literature?

I will now shortly sketch the history of the movement from the first separate efforts of individual reformers to the triumphant re-establishment of the national language, and you will note for yourselves how almost each initial step and phase through which the movement passed closely resembles what has been going on under our eyes in Ireland for the last ten years.

There is, however, one marked difference at the outset. In Hungary the desire to reinstate the old language remained for a long time confined to a few enthusiasts, who worked on in isolation or in small groups before they arrived at any concerted action. No such large and popular body as the Gaelic League came to their help. Perhaps the earliest outward sign of a coming change was the foundation in 1780 of the first newspaper in Hungarian, which was published by one Mátyás Rát, in the town of Pressburg, or Pozsony, as the Hungarians call it.(2) This was the “Fáinne an Lae” of Hungary.(3) As it proved an unexpected success, it was soon followed by a number of non-political papers which opened their columns to literature and poetry, and every interest of national life.

The smaller groups of enthusiastic young men now began to form into societies for the purpose of cultivating the language, studying the older literature and the history of their country. Under the leadership of János Kis in Sopron(4), Anton Cziráky in Pest(5), and George Aranka in Transylvania (6), they gradually obtained a wider influence, especially among the aristocracy of the country.

The period from 1807-1830 in Hungary bears in many respects a striking resemblance to the present state of the Gaelic movement. It was a period of preparation, of laying the foundations, of learning and of criticism. But the most gifted among the groups which I have mentioned began also to write and publish, and to show by example what the language was capable of achieving in literature.

Some translated and adapted the masterpieces of ancient and modern literature, others took for their model the old native songs and epics, others again more boldly struck out new lines and enriched Hungarian literature by original compositions.

You can almost in reading the history of this period single out individual writers and compare them to men now working on similar lines in Ireland. There was, e.g., the Hungarian Æsop, as he was popularly called, one Andrew Fáy(7), who, like Father Peter O’Leary(8), reproduced the Fables of Æsop in the native language. But perhaps the closest parallel is to be found in the first attempts made to found a national drama. Up to this time there had been no national stage. Only French or German plays were performed. But now a large number of plays were written in Hungarian and on Hungarian subjects; travelling companies of amateur and professional actors were formed and set up their stage in many towns of the country. A rich repertoire of native dramatic literature gradually arose. Apart from all other advantages, this migratory theatre had the effect of setting a model of correct pronunciation before the people. But all these efforts, much good as they did in some ways, were still felt to fall short of their aim. They did not lay hold of the younger generation that was growing up; nor did they work for unification, but rather for separation. For the disintegrating effect of the dialects began to show itself. The need of a centre to organise and direct the necessary work, the creation of a standard language, and the introduction of the movement into the schools and colleges, were now felt to be the most urgent needs. Two proposals which had already been made at an earlier stage, though they had not then been acted upon, now took effect.

As early as 1793, at a literary soirée, József Kármán had pointed out to his fellow-workers the necessity of making the capital of Pest the centre of the movement.(9) Some remarks of his are worth quoting literally. After having mentioned what their cause owed to patriotic men in Vienna, Komárom, Kassa, Debrecen (10), Transylvania, and other places, he proceeded as follows: “Unless a common centre is now created to unite all those local efforts, the dialects will never merge into a universal, uniform standard language; nor will these isolated provincial efforts produce a national literature which alone is able to level and harmonise the differences of language, taste, and individualism.” He then pointed out the claims which Pest possessed in its society, its libraries, its printing presses, etc, for becoming such a centre. But how exactly this centralisation was to be carried out by Kármán did not in detail put forth. In any case a whole generation passed before his dream was realised. It was only when a new item was realised. It was only when a new item in the programme began to be coupled with the idea of making Pest the headquarters of the movement that it was carried out. This new idea was the foundation of a national academy in Pest. The finest intellects of the nation, the most distinguished writers, the best trained scholars, the most expert workers were to unite to organise the movement on educational and scholarly lines, to set the necessary standard in language and literature, to create a national Press, in short to do not only what the Gaelic League has endeavoured to do, for Ireland, but to do systematically and methodically what is now left to the efforts of individual writers and scholars.

Strengthened as the men who undertook this work were by the implicit trust of the nation that had committed their task to them, they achieved it triumphantly within the incredibly short period of one generation. The academy was founded in 1825, but did not set to work properly before 1830. In 1865 its members considered their task done, dissolved and reconstituted themselves into an ordinary Academy of Sciences such as most capitals of Europe possess.

Now to anyone who studies the various phases of the language revival in Hungary, it will become apparent that the chief reason of its unparalleled success is to be sought in the foundation of this academy. Indeed the Hungarians themselves regard it as the turning point in the movement. For the results now attained in quick succession surpassed the hopes of the founders themselves. Let me read to you what a cool chronicles of the movement, Mr. Butler of the British Museum, who wrote the article on Hungary in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, says on his head:

“The establishment of the Hungarian Academy (1830) marks the commencement of a new period, in the first eighteen years of which gigantic exertions were made as regards the literary and intellectual life of the nation. The language, nursed by the Academy, developed rapidly, and showed its capacity for giving expression to almost every form of scientific knowledge. By offering rewards for the best original dramatic productions, the academy provided that the national theatre should not suffer from a lack of classical dramas. During the earlier part of its existence the Academy devoted itself mainly to the scientific development of the language and philological research.” (11)

It was in the year 1825 that the Academy was founded by the generosity of a patriotic nobleman, Count Széchenyi, who devoted his whole income for one year to the purpose, about £6,000. (12) Very soon, however, the new institution was supported by contributions from all quarters, except the Government, and was thereby enabled to carry out its many-sided and difficult task,

Let me quite briefly enumerate the chief items of the work accomplished by the academy during the thirty-five years of its existence.

One of the first cares of the Hungarian Academy was to fix the orthography of the language: they set a standard of a uniform literary language by checking on the one hand the encroachments of the dialects and on the other those of foreign idiom and vocabulary, and by developing the inherent powers of the language; they brought out standard dictionaries, grammars, books on the philology and history of the language: they printed the older literature in accurate scholarly editions, and supported the best contemporary writers by every means in their power; they organised and directed the teaching of the language in the schools, and thus brought up a new generation proud to be Hungarians and fully conscious of the possession of a fine and cultivated language and of a noble national literature.

There are now followed such an outburst of literature as had not been witnessed before, Masterpieces of prose and poetry appeared which for the first time drew the attention of the world upon Hungarian literature. I refer, e.g., to such writers as Mór Jókai, (13) the great novelist of Hungary, whose works have been translated into every European language; and to the poet Sándor Petőfi, (14) the Burns of Hungary (15), best known to English readers by the translations of Sir John Bowring (16). There can be no doubt that it was in the first instance the work achieved by the academy which rendered such immediate results possible.

From what I have said you will readily understand that I have come here tonight to plead before you, and through you before the Gaelic League throughout the world, for the speedy establishment of a Gaelic National Academy in Dublin on the lines of the old Hungarian Academy at Pest. I can do no more than throw out this idea, trusting that it will fall on fertile ground, that men and money will be found to carry it out, so that it may become a potent factor in the progress of the Gaelic movement.

If it were said that the existence of the Gaelic League makes such an institutions unnecessary, my answer would be that the League is far too large and popular a body to deal efficiently with such work as would fall within the province of an academy; that indeed it has so much to do already that a partial devolution of its work on to the shoulders of such an institution might be welcome to it. Moreover, much of the work that has to be done and can no longer be delayed is of such a nature that it can only be carried out in academic leisure and by comparatively few men.

It is only the best writers, the best trained scholars in the land who are competent to deal with it. There is no lack of such men and women in Ireland now. Many names will occur at once to everyone. Douglas Hyde (17), Father P. O’Leary (18), Dr. O’Hickey (19), Father Dinneen (20), Eoin MacNeill (21), Miss O’Farrelly (22), and others who have done such splendid work already, might constitute themselves as the first members of an academy. An appeal to the nation at large would raise the necessary money, or perhaps some Irish or American Széchenyi will be found to set apart funds for such a purpose.

As for the programme of work to be carried out by our Irish Academicians, or under their direction, I think they could not do better than follow point for point the programme of their elder brethren of Hungary. Perhaps you will bear with me a little longer while I sketch in greater detail one or two of the most urgent needs which I think should be committed to the care of an academy.

In the first place they would have to fix the orthography of Irish, which is now in a more chaotic state than it has probably ever been before. Some people may be included to regard a spelling reform as a trifle. It is essentially a task that can no longer be safely deferred or left to chance and caprice. I would ask them to remember how much depends on the ease and rapidity with which a child or beginner can learn to read and spell a language. It is one of the great advantages of modern Welsh, and one of the reasons why the language has retained a firmer hold of the people than any other Celtic language, that its spelling is so perfect, so consistent and easy to grasp, so that a child when it has but mastered the forms of the letters can learn to read and write correctly in a short time. A spelling reform, then, a rigorous standard, is urgently needed.

Next comes the even more important question of the dialects and the standard language. This, you will remember, was one of the points not settled in Hungary until the academy took it in hand. Indeed it cannot be settled by individuals, though naturally the best writers will always exercise a deep and lasting influence upon the literary language. If the problem is left to itself, it will take many generations before a standard national language will develop. Without such a standard, however, the beginner is sadly bewildered. He looks in vain for a pattern upon which to mould his language. It will not do in the 20th century to set up the model of a writer of the 17th, such as Keating.(23) The national language of every country is based upon an adaptation and compromise between living dialects. It incorporates what is either common to all, or so widespread that it is intelligible, or can easily become so, to the greater part of the people. It avoids all localisms or solecisms.

Another task awaiting our academical dictators is to free the language more and more from a slavish imitation of English idiom which now disfigures so many pages of Irish writing and makes it often impossible for the student to understand some of the Irish now written without first translating it into English, such phrases I mean as fághail amach, (24) déanamh amach, (25) deanamh suas na meanman, (26) teacht suas le, (27) etc. The best and standard Irish should draw instead upon the racy and unadulterated idiom of the best native speakers and scholars, as well as upon the inexhaustible store of genuine Gaelic preserved in the literature of the past. The reformers should next stem the tide and influx of load words from English and other sources, reduce it within proper limits and revive and reintroduce many an ancient Gaelic word, so that, e.g., instead of pósaidh (28) or plúr (29) the old word sgoth (30) may be heard once more.

It should not be forgotten that the Irish being the first Western nation to cultivate classical learning long ago developed expressive native terms of its own for every scientific term of Greek or Latin.

In mathematics and medicine, in astronomy and grammar, they had a perfect native terminology, including words for such terms as sodiac, superlunar, horoscopist, septentrio, etc.; and in grammar for denominative, hiatus, patronymic synaeresis, etc.

Among the minor points to which the academy should turn its attention is the restoration of the old native place-names of Ireland. Here, again, Hungary may serve as a model. Every town and village in Hungary has now its old native name restored to it. In Ireland, English pronunciation, the most rigid and unadaptive in the world, has sadly disfigured and vulgarised many fine old Irish names. Such caricatures as Shankill (31), Adavoyle, (32) Annalong, (33) and many others, should disappear from Irish topography.

But, indeed, it would take me far too long, and would weary you, if I were to go at the same length through all the problems and tasks which await out academy. Let me therefore conclude by pointing out the great need there is of books, good books and cheap. The workers of the League know how the lack of good Irish libraries hamper their efforts. The older books are all too rare and expensive now; and for lack of support or enterprise Irish publishers still allow much Irish literature to be published abroad. Is it not an anomaly that O’Donnell’s Life of St. Columcille should first appear in a German periodical?(34) Or that a scholarly edition and translation of the Midnight Court should be brought out in the same periodical rather than in Ireland? But indeed the books that are needed are so varied and numerous that one does not know where to begin in enumerating them. (35)

Dictionaries, English-Irish and Irish-English, etymological dictionaries of synonyms and phrases, grammars of the spoken and written language, histories of the language, text-books of all kinds, readers of older and modern prose and poetry, translations of the masterpieces of the older literature into modern Irish, editions of the literature buried in countless manuscripts, collections of folklore, Irish histories compiled from the best sources—these are but some of the most pressing needs of an Irish library. I am, of course, aware that in all these matters a beginning and a good beginning has already been made by the enterprise and energy of private scholars and societies. But they need support and encouragement, and a great deal remains to be done on a much larger scale. We have all welcomed the appearance of Father Dinneen’s Dictionary, and too much praise cannot be given to his scholarly and painstaking performance. But what is it but the first attempt to gather the modern Irish vocabulary, briefly and for immediate practical purposes? How far removed is it from a thesaurus of the living language with all its varieties and idioms, or of the whole Gaelic vocabulary, an Irish dictionary, which could take its place worthily by the side of the monumental dictionaries of other languages! Do what you will in the vast domain of Irish language and literature, for a long time to come there is no fear of exhausting it easily, or of interfering or overlapping with the work of others. But there is a well-grounded fear of urgent and necessary work being delayed, of other work being never done at all, of energies and talents being wasted because they are left unsupported or uncultivated, and of the progress of the great cause which we have all at heart being thus retarded.

Footnotes

János Illei (1725—1794) was a Hungarian Jesuit priest. Illei’s writing ought to be considered within the context of the Germanisation policies of Empress Maria Theresa (1717—1780) across Habsburg territories.

Mátyás Rát (1749—1810) founded the first Hungarian language newspaper, Magyar Hírmondó. The city of Pozsony, now called Bratislava, is the capital of modern Slovakia. It was previously the capital of Hungary from 1536—1783.

Fáinne an Lae, meaning, Daybreak, was the first bilingual Irish-English newspaper. Published from 1898—1900 under the editorship of Bernard Doyle, the paper was later controlled by the Gaelic League.

János Kis (1770—1846) was a Hungarian poet and founder of the Soproni Magyar Társaságot, or Sopron Hungarian Society. In the original printing, Dr. Meyer refers to Sopron by its German name, Ödenburg.

Count Antal Cziráky (1772—1852) was a Hungarian judge and politician. He was a founding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

György Aranka (1737—1817) was a Hungarian writer and lawyer. His poems were published in Magyar Hírmondó.

András Fáy (1786—1864) was a Hungarian poet, novelist, and playwright. He was a founder of the Hungarian National Theatre

Father Peter O’Leary (1839—1920) was an Irish Catholic priest. Father O’Leary was a key figure in the revival of Irish-language literature through the serialisation of his novel, Séadna.

József Kármán (1769—1795) was a Hungarian author and lawyer. He created the Hungarian literary journal Uránia.

The cities of Komárom and Kassa are now part of Slovakia, known by the names Komárno, and Košice respectively. Situated in the east of Hungary, Debrecen is the second-largest city in the country.

Samuel Butler (1774—1839) was an English scholar, and Anglican Bishop.

Count István Széchenyi (1791—1860) was one of Hungary’s most important statesmen. He is considered by some to be the greatest Hungarian to have ever lived.

Mór Jókai (1825—1904) was a romantic novelist who wrote numerous works in the Hungarian language.

Sándor Petőfi (1823—1849) is considered the national poet of Hungary.

Robert Burns (1759—1796) is considered the national poet of Scotland.

Sir John Bowring (1792—1872) was a British diplomat and literary figure

Sándor Petőfi (1823—1849) is considered the national poet of Hungary.

Douglas Hyde (1860—1949) was co-founder and first president of the Gaelic League and later the first President of Ireland. Hyde’s Irish penname was An Craoibhín Aoibhinn, meaning, the pleasant little branch.

Father Dr. Michael O’Hickey (1860—1916) was an Irish Catholic priest and Professor of Irish at Maynooth College. O’Hickey served as vice president of the Gaelic League, and was a member of the Royal Irish Academy

Father Patrick Dinneen (1860—1934) was an Irish Catholic priest and leading figure of the Gaelic Revival, through his work for the Irish Texts Society and the publication of his 1904 Irish-English Dictionary.

Eoin MacNeill (1867—1945) was an Irish scholar and Cumann na nGaedheal politician. MacNeill was a co-founder of the Gaelic League, and leader of the Irish Volunteers. Dr. Meyer renders MacNeill’s first name as John in the original printing.

Agnes O’Farrelly (1874—1951) was a Professor of Irish at University College Dublin and founding member of Cumann na mBan.

Geoffrey Keating (1569—1644) known in Irish as Seathrún Céitinn, was an Irish historian and Catholic priest. Keating’s Foras Feasa ar Éirinn—translated as Foundation of Knowledge on Ireland, or The History of Ireland, remains one of Ireland’s most significant historical texts.

The phrase "fághail amach" translates to “leave out” or “work out” however it is ambiguous without context. The participle “fághail” should be rendered as “fág amach” in isolation, or as “a fhágail amach” with context.

The phrase "déanamh amach" translates to “work it out.” It can be rendered in modern Irish as “leagan amach.”

The phrase "déanamh suas na meanman" translates to “lift your spirits.” In modern Irish this may be presented as “cinneadh a dhéanamh” or as “ordú meanman.”

The phrase "teacht suas le" translates as “to devise.” A modern variation of this phrase would be “seift a cumadh.”

The term "pósaidh" refers in modern Gaeilge to the simple word “pósta,” the genitive singular of “pósadh”, meaning marriage.

The word "plúr" refers to the word for “flour” or “blossom.”

The word "sgoth" here is an outdated spelling of "scoth" in modern Gaeilge, which also translates to blossom.

Shankill, spelled by Dr. Meyer originally as “Shankhill” or in Irish Seanchill, meaning Old Church, is a town in County Dublin.

Adavoyle, or Achadh an Dá Mhaoil, meaning Meadow of the Two Knolls, is a rural townland in County Armagh.

Annalong, or Áth na Long, meaning ford of the ships, is a seaside town in County Down.

Manus O'Donnell (1490–1563) was the King of Tyrconnell. O’Donnell was responsible for commissioning the Life of St. Colmcille—in Irish Beatha Cholm Cille—which he partly wrote.

Brian Merriman (1747—1805) was an aisling poet. Merriman wrote the Midnight Court, known in Irish as Cúirt an Mheán Oíche.