Assimilating Others and the End of History

This article was originally published on the Substack ‘maoltuile’

We thank Gearóid Maoltuile for permitting its syndication on MEON.

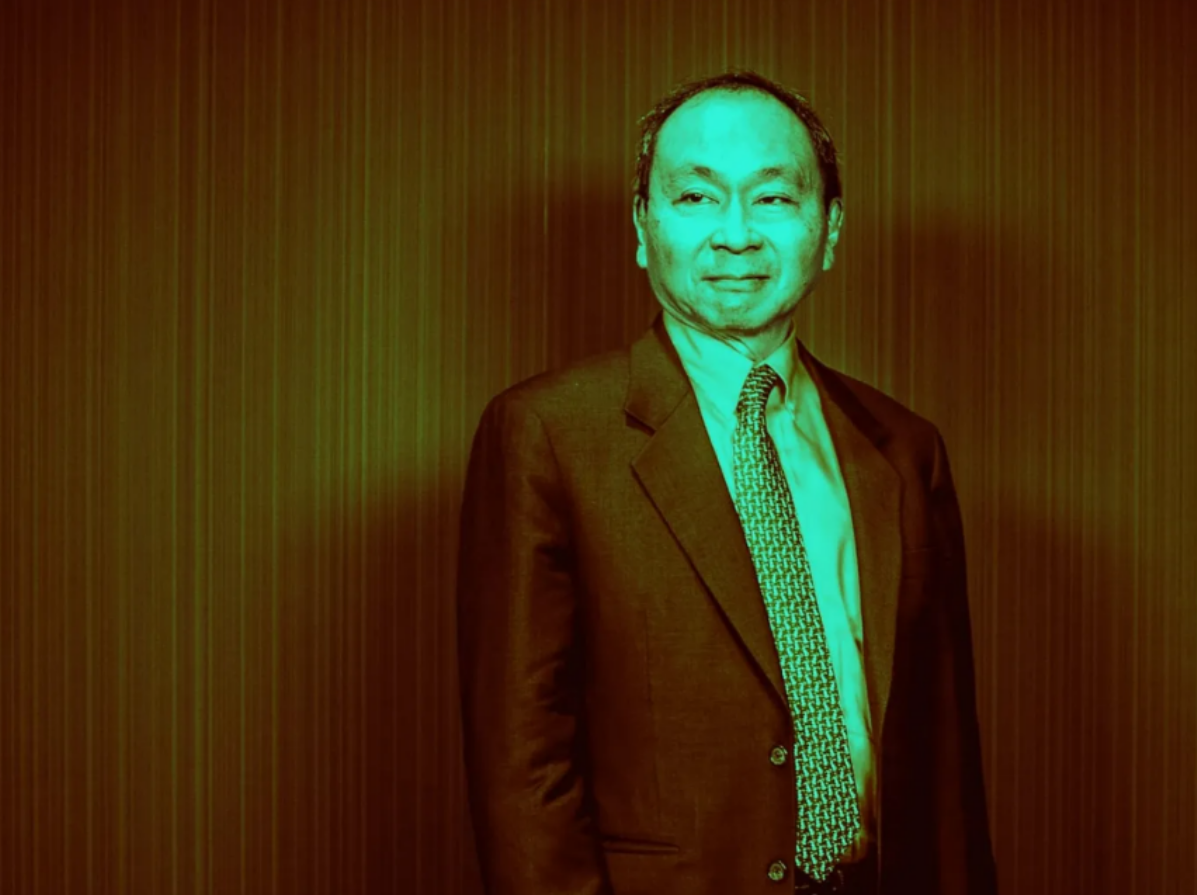

Yoshio Fukuyama was born in the United States of America in 1921, son of Japanese Christian immigrants. Shortly after the Second World War, he married Kyoto born Toshiko Kawata. In 1952, their first and only child was born, Francis Fukuyama. Yoshio Fukuyama received a degree in sociology from the University of Chicago, an institution that was soon to gain global recognition for it’s defence of capitalism and the promotion of free-market economics. Yoshio went on to become a Christian scholar and theologian, developing the 5-D thesis, a scientific method for measuring religiosity.

“In its economic manifestation, liberalism is the recognition of the right of free economic activity and economic exchange based on private property and markets. Since the term "capitalism" has acquired so many pejorative connotations over the years, it has recently become a fashion to speak of "free-market economics" instead; both are acceptable alternative terms for economic liberalism” - Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man

From the year of Francis’ birth to the fall of the Berlin wall in ‘89, the young Fukuyama had a solid system of values and national mythology to help graft his identity to the White American society that surrounded him, Christianity and capitalism. A clear sense that he was running with the pack would be easy to come by, conflict between Japan and America had ended with no return on the horizon and both nations stood in opposition to Soviet Russia and Mao’s communist China.

America’s liberal utopianism shared it’s youth with Francis, it’s inception coming in the interwar period with the implementation of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal but coming into full bloom in the post-war era. The Black Civil Rights movement was centre stage in American politics during Francis’ childhood. His father Yoshio became a Director of Research at the United Church of Christ, a liberal Christian denomination, which played an active role in the promotion of Martin Luther King and the censorship of his opponents, often taking broadcasters to court on behalf of the Civil Rights movement, having broadcast licences removed from political opponents on the grounds of racial or religious discrimination.

The implementation of liberal utopianism had since it’s beginning been a response to, rejection of, and to certain extent a copy of the other great utopian revolutions of Western civilisation in the 20th century, which appeared most dramatically in Germany and Russia, and also in Ireland. The grand narrative was clear, America was not in a simple struggle for power with competing empires but was fighting for the soul of the West, which in the eyes of Westerners represents all of humanity.

As the Soviet empire collapsed in the late 80’s and early 90’s, the story of European civilisation opened itself to reassessment again. It is easy to imagine an elder Anglo-American breathing a sigh of relief as the struggles 20th century came to an end, life might just be normal again, their descendants would be free from these great dramas. But not so for the Fukuyama family, reliant as they were on ideological alignment with their neighbours, unable to default to ancient kinship ties and with little family history in the West predating the New Deal’s liberal revolution.

What remained to align the Fukuyama family politically with their White American neighbours now that the threats to capitalism and Christianity had subsided? How fervently would the United States of America pursue it’s liberal revolution now that the soul of the West had been saved from communist Atheism? The United States, which had comfortably assimilated the Fukuyamas along ideological lines, was due an update for this new world order, a revision of it’s narrative, history and ideas, an update that Francis Fukuyama was keen to delay indefinitely. In 1992, Francis Fukuyama released the book that made him famous, “The End of History and the Last Man”.

“What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” - Francis Fukuyama, the End of History and the Last Man.

Throughout the text, Fukuyama concerns himself with universalist political concepts, seeing the only threat to universal liberalism coming in the form of Islam, which is written off as unappealing to those without Islamic heritage while dismissing the notion that the distinctly European and largely Anglo ideals of liberalism could be unappealing to those without European heritage. His confident statement of fact that Islam has “no resonance for young people in Berlin” has aged terribly and shows us how migration has altered the politics of the West in such a short period of time.

An attempt is made to draft a history of universalism for a new universal community, which reads as a simple European history, Fukuyama plays the role of Whig historian, charting the progress of universalism from Plato through to exclusively European Christian thinkers, with the inclusion of Karl Marx and Henry Kissinger. The only acknowledgement of a world outside of the West comes with a mention that Hegel, Spengler and Toynbee once acknowledged a world outside of the West. The history of Western civilisation for Fukuyama is the history of universalism and exists only to justify his membership of it.

The European Union lists it’s values as human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, rule of law and human rights, a fine summation of liberal values in the West. If one is to become an assimilated European, these are the values that one must adhere to. The European identity of the assimilated other is tied to these values in way that will never be true for native Europeans. The European identity of the native European is never in question, we are free to pick and choose our values, a freedom not afforded to the assimilated other. Hearing Europeans like myself criticise such values is a painful experience for assimilated others who have devoted themselves to what they understand to be my values and I have a great deal of sympathy for them in their strange situation.

Fukuyama is a small but obvious example of the zealous adherence to liberal values and universalism by assimilated others within Western civilisation. We see this in voting patterns across the West and more troublingly, in how the assimilated other perverts our relations with the non-Western world. The universal empire is a world empire in the waiting. For the assimilated other it is a matter of high importance, if the Japanese were to fork off into a particularist future of their own, the Fukuyamas would be viewed with the same suspicion that Chinese people live under in the West.

Organisations like the National Endowment for Democracy and the various front groups of Western imperialism are staffed largely by assimilated others. Any liberal Iranian living in the West will make it clear to you with no sense of shame that they view it as the responsibility of White Western peoples to fight battles to bring liberal utopianism to Iran, presumably while they relax in a Western country and scroll a social media feed watching destiny unfold. The existence of the Islamic Republic is more than a social embarrassment, it’s survival into the future risks breaking the universalist perspective of White Western people. If our perspective were to shift, our assimilated new neighbours will find themselves with different values to our own, unassimilated once again and perhaps unwelcome in the West.

“Instead of being about the future, 21st-century culture is increasingly haunted by the past. The 'futuristic' has been slowly cancelled.” - Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life

Mark Fisher deals extensively with the End of History in his writings. He argues that the future has been cancelled by a pervasive nostalgia, we are cursed to reboot the Star Wars franchise ad infinitum due to a postmodern inclination toward reordering what already was, unable to think new thoughts. He notes an important pattern in our liberal culture but fails to properly understand it. Progress and imagination in European civilisation (the Renaissance and the French revolution are shinning examples) has always been an act of searching through our past and reordering what is old, bringing the old back into fashion, reimagining ourselves as Ancient Romans in new and exciting ways with all of the knowledge that we’ve accumulated since. Returning to an imagined ‘state of nature’ was a fundamental argument employed by visionaries in every European revolution. A revolution in European culture is a return to something that went before and this will continue to be so.

“In ancient Ireland, under the Brehon Laws, the land of Ireland was owned by the people” - James Connolly, Labour in Irish History

The reason for the frustration felt by White Westerners is not that we’re increasingly nostalgic for the past, this behaviour is perfectly ordinary to us. The frustration is that we no longer have much of a past to return to, we are forced to run in small circles from the beginning of the New Deal onwards. Every example cited by Mark Fisher of culture being rehashed is an example of post-war liberal culture. We are unable to reimagine anything that predates that liberal revolution because our assimilated new neighbours do not share our heritage. Fukuyama cannot imagine with us that he is an Ancient Roman, nor does he wish to, another such revolution risks excluding him forever. European history before the liberal revolution exists to justify the universalist and anti-racist positions of liberalism, anything else is uninteresting, offensive and a danger to the assimilated others.

The slow cancellation of the future is the abrupt cancellation of our history. Our liberal revolution appears as the last one possible to us because it was the last time a Western society was homogeneous enough to reimagine itself. Creative reimagining requires vast amounts of shared history, a great heap of old ideas to sort through. Whether Europeans can find the courage speak up and bravely reference our pre-liberal history, reimagining ourselves again as Ancient Romans, or in the Irish case as Breton law abiding clansmen, in the face of the inevitable accusation that our dreams are not inclusive is the challenge facing our generation across the West, failure to meet this challenge will leave us to reimagine that small patch of the 20th century forever.