Governing Without FG or FF: Clann na Poblachta as a Case Study

This essay was originally featured on Cennétig’s Substack and is syndicated with the author’s permission.

Want to write for MEON?

Get in touch: meonjournal@mailfence.com

It has been remarked by many commentators that the ‘potential does now exist for a government without either FG or FF for the first time in the history of the State.’ However, this isn’t entirely accurate. Reading into the history of Irish elections, we see parallels of contemporary times in the run up to the 1948 general election.

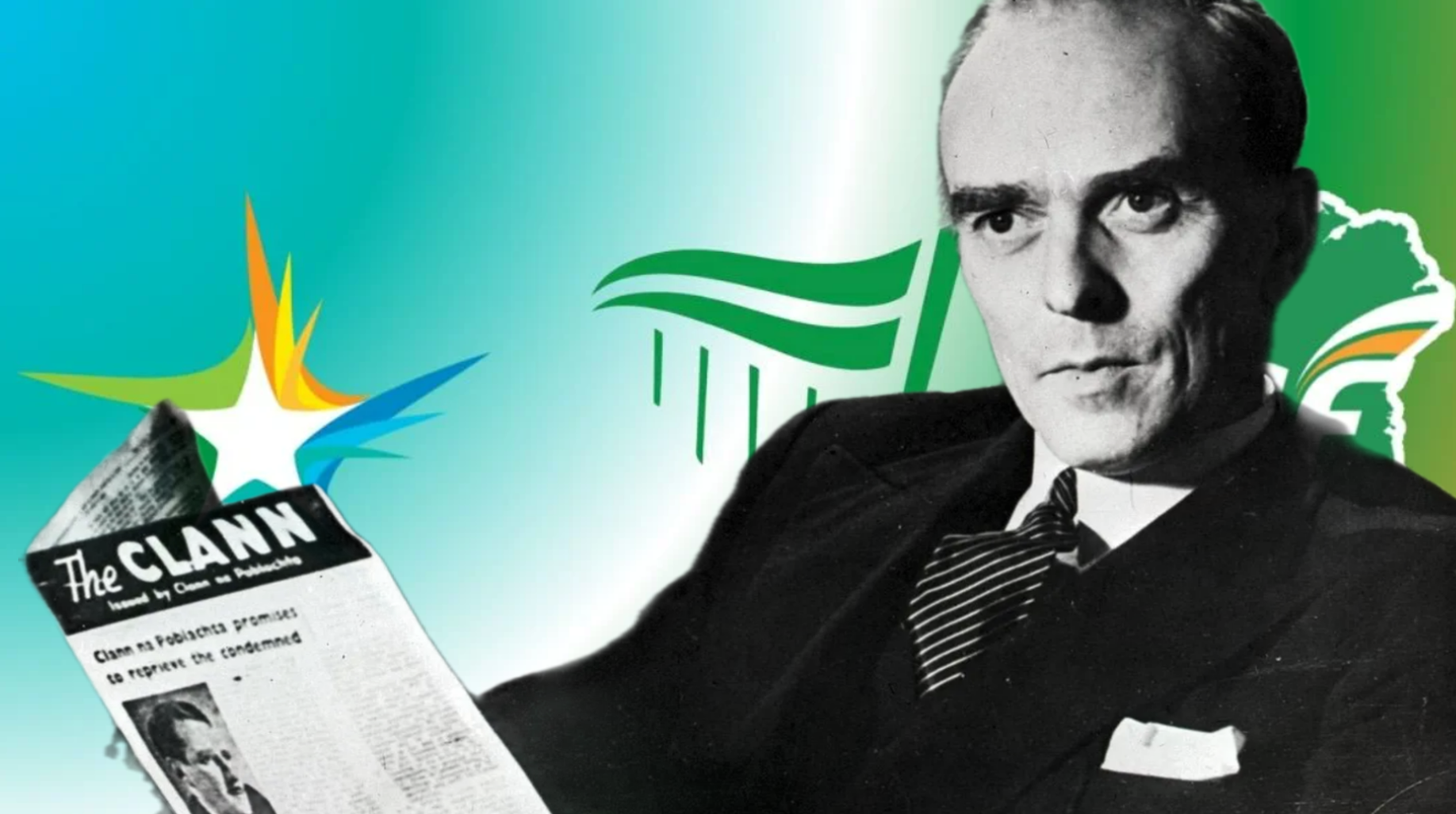

The party with the potential to oust both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil was Clann na Poblachta, led by republican veteran and Amnesty International co-founder Seán MacBride. The election of 1948 would be the first general election that Clann na Poblachta would contest, and their hopes were high—and not without reason.

Doubts emerge about Fianna Fáil’s republican credentials

As the 1940s wore on, Fianna Fáil's republican credentials begun to be questioned for the first time in their history. Keeping in the tradition of hypocrisy that Free Staters have become known for, having condemned Cumann na nGaedheal from the opposition benches for ruthlessly persecuting the IRA in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Fianna Fáil initiated its own ruthless campaign against the IRA from the late 1930s onwards.

As the relatively recent IRA campaign of the 1970–90s still lingers in the consciousness of the Irish people—being within living memory for many—it is often forgotten that the Fianna Fáil governments under de Valera treated IRA members in ways not far removed from how British authorities would treat them during the troubles.

The Gardaí, just like the RUC, had their own Special Branch whose modus operandi was to hunt down the IRA to the extent that they gained a ‘shoot-first-and-ask-questions-later’ reputation. Internment without trial was introduced, military courts where defendants had next to no rights to a fair trial were set up, IRA prisoners’ were treated as criminals rather than political prisoners, the press was censored, executions were carried out, and eventually a showdown between the IRA and the authorities occurred over some prisoners decision to go on hunger strike.

The electoral evidence of a republican backlash against Fianna Fáil can be seen in the 1945 presidential election. The republican dark horse of the race, Patrick McCartan—standing as an independent—surprised the establishment by receiving nearly 20% of the first preference votes. Not only this, the distribution of his transfers flowed more towards the Fine Gael candidate—receiving 55% of these transfers—than to Fianna Fáil—who received only 13%.

The final count saw Fianna Fáil go from just under 50% to 56%, while Fine Gael jumped from 31% to 45%. This worrying trend of republicans preferring the Commonwealth party over the self-described ‘republican party’ could spell disaster for Fianna Fáil’s dominance if this trend continued.

Demise of Fine Gael

Beyond vote transfers from republicans, Fine Gael in the run up to the 1948 general election had had little else to be hopeful for. The party was founded shortly after the defeat of Cumann na nGaedheal in the 1932 election, and was a party that had lost sense in the reality of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 being merely just a stepping stone to greater freedom. It was a party that represented the Anglophile and the wealthier elements in society—a dwindling demographic that would sink the party with it.

Fianna Fáil in power and the new constitution of 1937 meant that Fine Gael framing themselves as the party of the protector of the state and the constitution—or to use their euphemism, the party of ‘law and order’—meant that one of the core reasons for the party’s existence had effectively disappeared.

Fianna Fáil had now become the party of the ‘law and order’—having drafted and enacted the new constitution and persecuted the IRA—and the party of republicans—having abolished the oath of allegiance, reclaimed the Treaty Ports, and done away with the ‘Treaty of Surrender’. Just as Sinn Féin had done to the SDLP post-Good Friday Agreement—by moving towards SDLP’s politics of constitutionalism while still claiming the republican mantle—Fianna Fáil now moved towards Fine Gael’s political sphere of ‘law and order’, while trying to hold on to their traditional republican voting base, thus rendering Fine Gael’s reason for existing null and void.

The 1948 election and the republican threat to Fianna Fáil dominance

With Fine Gael declining into irrelevancy, the prospect of being flanked by a republican party on the other side of political spectrum now became a real worry for Fianna Fáil. The by-elections in the run up to the general election of 1948 would be a litmus test for public opinion, in the same way it was for Sinn Féin in the lead up to the 1918 Westminster election. The defeat of another independent republican candidate, the War of Independence veteran Tom Barry, in the Cork by-election of 1946 was the event that spurred republicans to coalesce days later to establish their own party, Clann na Poblachta.

Like Sinn Féin of the 2000s, Clann na Poblachta drew its candidates from the veterans of the most recent IRA campaign. The provisional executive of Clann na Poblachta ‘sounded like a roll-call of the 1930s IRA,’ with at least twenty-two of the twenty-seven members being volunteers in the IRA at some point in their lives. The three by-elections in 1947 would be the testing ground to see if Clann na Poblachta had the public support they claimed they had. The results were a breakthrough for the party, securing two out of the three seats, with Fianna Fáil maintaining the remaining seat.

With two seats claimed, their hopes for the upcoming 1948 general election were high. On the eve of the election, Clann na Poblachta’s director of elections, Noel Hartnett, declared that the Government was ‘going to get its greatest pasting ever,’ and he expected that his party would secure at least 30% and at most 51% of the seats available.

Failing to secure a majority, Clann na Poblachta members thought that going into a coalition government with the Labour Party, National Labour Party, and Clann na Talmhan would secure the majority they needed. Notably, Fine Gael would hopefully be excluded from this coalition—due to them being unrepentant Free Staters—and Clann na Poblachta would be the undisputed dominant party in the government.

Parallels between contemporary Sinn Féin and Clann na Poblachta

These set of circumstances are very similar to the hopes of contemporary Sinn Féin and the hypothesised ‘left-wing coalition’ that would exclude both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. Both Sinn Féin and Clann na Poblachta would ally themselves with minor parties that stand for minority interests. In the time of Clann na Poblachta, these minority interests were the interests of the urban working-class and the rural farmers. In contemporary times, these minority interests are the politics of sexual hedonism and bohemianism on the one side, and the youth vote disgruntled with the housing crisis on the other.

Both Sinn Féin and Clann na Poblachta had a voting base that leaned more towards the young. And just like in contemporary times, as a Fianna Fáil member in the run up to the 1948 election stated, there was a quarter of a million voters under the age of 25 that ‘do not believe that there is any substantial difference between us [Fianna Fáil] and FG.’

In the run up to the 1948 election, a major theme of Fianna Fáil’s attack on Clann na Poblachta was to associate them with communism and socio-economic radicalism. Ironically enough, the same Red Scare tactics were used on Fianna Fáil by Cumann na nGaedheal only over a decade prior. The Red Scare tactics have become outdated in current times, so contemporary Fianna Fáil portray Sinn Féin as a threat to our ‘enterprise [tax haven] economy.’

With the election results coming out, all eyes were on Clann na Poblachta. Would they come out triumphant and oust Fianna Fáil after 16 years of being in government? Fianna Fáil were ousted from government, but Clann na Poblachta had very little to do with it, achieving only 10 seats in the final count. This low number of seats was partly to do the fact that their 13% of the voting share only translated into 7% of the seats.

After Clann na Poblachta’s successful by-election results of 1947, De Valera called an earlier election than needed in order to reduce the amount of time the new party was given to organise itself. The results show that De Valera’s plan worked as Clann na Poblachta were faced with the onerous task of establishing their party and dislodging the local political hierarchies that had been given the time to entrench themselves for over a quarter of a century.

The online buzz about contemporary Sinn Féin leading a left alliance to oust both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil slightly deluded some social media users to think that this was inevitable. The number of followers that political parties have gives us a crude measurement of the extent of public engagement with each party. Sinn Féin have 186k followers on X, while Fine Gael have only 62k and Fianna Fáil 53k.

In comparison to the minor parties, Labour actually have more than Fianna Fáil at 54k, Greens have 41k, Social Democrats 32k, and People before Profit 28k. These numbers would give us the impression that Sinn Féin would easily lead a left coalition, but public buzz about a party doesn’t necessarily transfer into votes. The silent votes of older conservative voters will inevitably push the balance in favour of the status quo.

Clann na Poblachta in the run up to the 1948 election had a similar inflated attention with the public. In Dundalk more than 4000 people turned out to hear the party leader Sean MacBride speak, while only 2000 votes were secured in the county of Louth come the election. Clann na Poblachta even achieved bigger audiences than Fianna Fáil in De Valera’s home county of Clare, but Fianna Fáil ended up securing more than five times the amount of seats.

Clann na Poblachta’s mistakes and contemporary Sinn Féin

The lessons to be learnt from Clann na Poblachta is in their subsequent demise. The party went into coalition with Fine Gael, the Labour Party, Clann na Talmhan, and the National Labour Party after the 1948 election with Fine Gael playing a leading role. This coalition was a godsend for Fine Gael as it secured for them a reason for existing, which was that they were an alternative government to Fianna Fáil. This was the election that begun the process of the public becoming conditioned to voting for Fine Gael if they didn’t like Fianna Fáil and started the seesawing between the two parties for the next 70 years.

By going into coalition, Clann na Poblachta kept Fine Gael alive and discredited themselves in the face of the public who saw them as just another political party. Parties grow in opposition and tend to decline in government, and the decline is especially severe when its a small party in government. Going into government on their first election stifled any chance for Clann na Poblachta to grow, and becoming a junior partner in a coalition, solidified their status as a minor party. The Labour Party was also victim to this as there was a possibility of them becoming one of the two duopoly parties of Ireland with the decline of Fine Gael.

Sinn Féin haven’t made the first error by going into government too early—although Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael took that choice away from them anyway by shutting them out of any government formation. The second mistake that Clann na Poblachta made that Sinn Féin could avoid is going into government as a junior partner. If Sinn Féin hold out until a left alliance is possible with them in the lead, their solidification as Ireland’s premier party will be secure.

Further Reading / Source:

Ó Beacháin, Donnacha. The Destiny of the Soldiers: Fianna Fáil, Irish Republicanism and the IRA, 1926–1973.