The Curious Case of the Corrib Gas Field: Corruption, Capture, and the Cost of Sovereignty

The Corrib gas field, discovered off the coast of County Mayo in 1996, was hailed as one of the most significant energy finds in Irish history. At its production peak, it was estimated to meet over half of the country’s gas demand. Corrib should have been a flagship project in national resource management. Instead, it became one of the most contentious developments in modern Irish politics, marked by protests, secrecy, and systemic failure in public oversight.

This is not just a story of a botched energy project. Corrib is a case study of how a state can lose control over strategic assets through policy drift, inadequate institutional safeguards, and opaque relationships between public authorities and powerful corporate actors. It remains a cautionary tale of how the promise of energy security can be undermined by poor governance and the silent encroachment of foreign interests.

Corrib’s Origins: A Resource Mismanaged

From the outset, Corrib was developed under licensing terms that were curiously generous to private interests. Under regulatory changes introduced during the 1980s and 1990s, the Irish government offered developers 100% ownership of extracted gas, with no royalties and deferred tax liabilities. These terms, which were far more favourable than those in other gas-rich European countries, were quietly maintained as Corrib passed through planning and permitting stages.

Shell E&P Ireland led the project, which was later joined by Norway’s Statoil and Canada’s Vermilion Energy. From an operational standpoint, Corrib was a high-stakes engineering effort, requiring an undersea pipeline, an onshore refinery in Bellanaboy, and significant land acquisition. However, the project’s technical complexity paled in comparison to the political and social controversy it generated.

Public Backlash and Policing the Pipeline

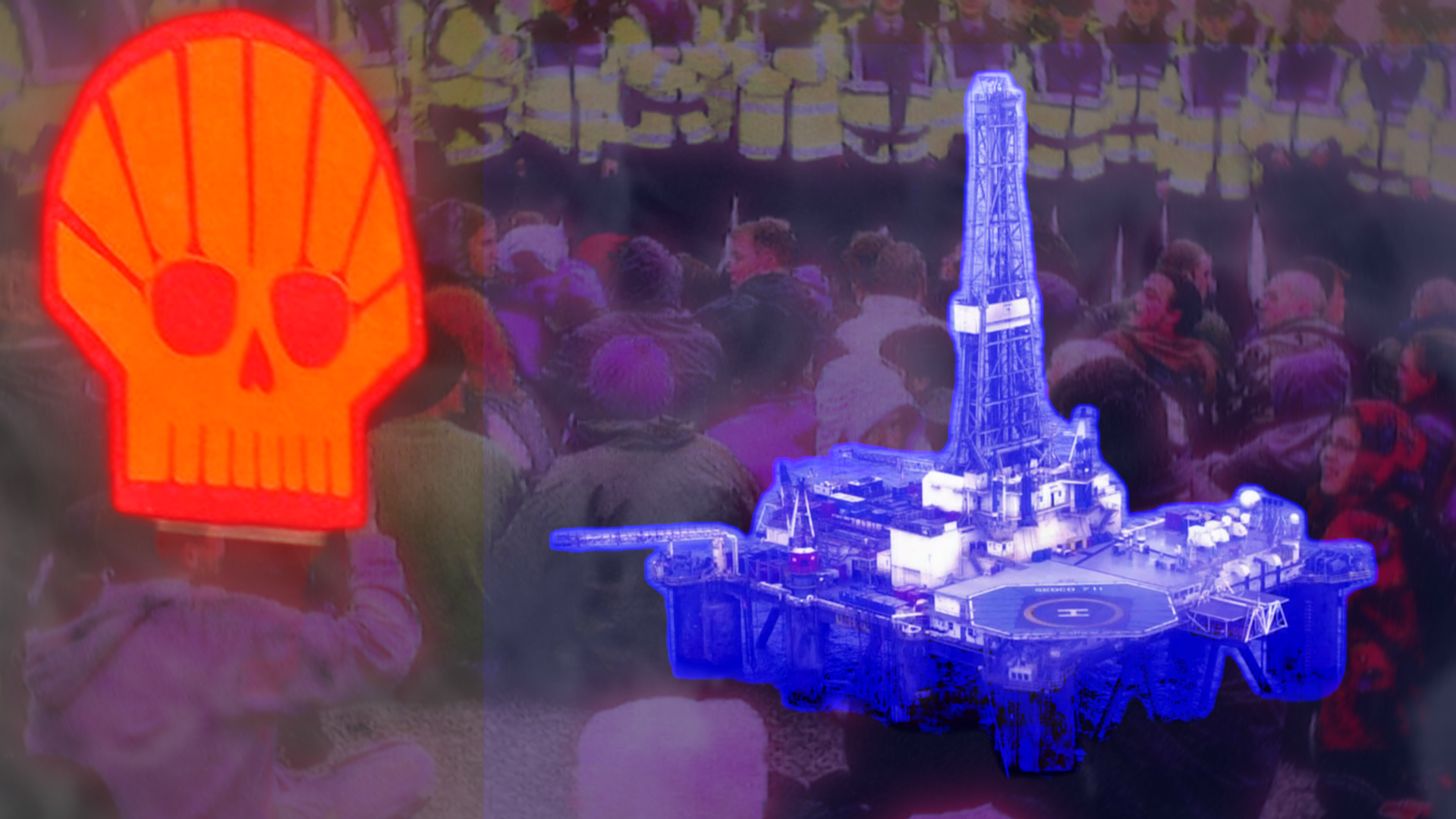

What followed was two decades of grassroots resistance. Local communities, particularly in Erris and Rossport, objected to the environmental risks posed by the high-pressure pipeline and to the broader implications of ceding control over a vital resource to foreign corporations. The protests escalated after the so-called “Rossport Five” imprisonment in 2005, which galvanised national and international attention.

What began as a local environmental struggle evolved into a much larger critique of how the Irish state handled corporate accountability, planning permissions, and public safety. Protesters were met with heavy policing, surveillance, and even private security operations — all too common occurrences in contemporary Irish civil strife, often appearing disproportionate to the stated threat, and heavy-handed in violence to instil fear and dissuade civic momentum. For many observers, it felt like the state had sided unequivocally with the corporate consortium against its citizens.

Tribunal inquiries and parliamentary questions followed, but no substantive reform of Ireland’s energy licensing regime occurred. Nor was any credible investigation launched into how decisions around Corrib were made, or who profited from its facilitation.

The Veil of Secrecy

Despite the national importance of the Corrib field, the process by which Shell and its partners gained access, approvals, and legal support was never subjected to robust democratic scrutiny. Planning permissions were granted through segmented applications that evaded holistic environmental assessments. The state vigorously fought legal challenges on the consortium’s behalf. State institutions, including An Garda Síochána, were repeatedly criticised for their handling of protests, with allegations of excessive force and interference surfacing in multiple independent reports. Interference at the behest of foreign capital and greed to the detriment of Irish citizens seems to have crystallised in the culture of policing since the heavy-handed approach towards the local protests in the early 2000s.

Media investigations also revealed a pattern of revolving doors between regulators, policymakers, and industry consultants, suggesting a close-knit ecosystem of mutual benefit and limited transparency. Access to internal communications, particularly those between civil servants and industry representatives, was tightly controlled or redacted. Public confidence eroded further with each revelation.

Foreign Interests and Strategic Blind Spots

Though Corrib was officially developed by Western energy companies, Irish regulatory laxity and the absence of sovereign safeguards raised concerns about strategic vulnerability, at the time of Corrib’s development, Ireland lacked a national energy security strategy, a sovereign wealth mechanism, or any oversight authority dedicated to monitoring foreign influence in critical infrastructure.

This vacuum made Ireland an unusually soft target, not only for private profit but also for geopolitical leverage. While no formal evidence has emerged implicating specific foreign state actors, the precedent established by Corrib, namely, full ownership of national resources by non-Irish companies with minimal state oversight, has implications far beyond economics.

In the years since Corrib’s operationalisation, European energy policy has shifted dramatically. The war in Ukraine, the weaponisation of gas flows, and fears over critical infrastructure sabotage have all forced EU member states to reassess how they protect and govern energy assets. In this context, Corrib now appears not just flawed but dangerously naïve.

Institutional Weakness and Policy Drift

Corrib’s legacy also highlights how policymaking can drift under the weight of inertia, informal influence, and weak institutional design. Ireland’s licensing framework for fossil fuel exploration remains among the most liberal in Europe. No public royalty scheme exists, and no independent strategic infrastructure oversight body is formalised. Planning, environmental, and commercial decisions remain siloed across different departments, committees and agencies.

This fractured architecture enables exactly the piecemeal decision-making that allowed Corrib to pass through multiple approval stages without a national debate on ownership, revenue sharing, or long-term energy planning.

Furthermore, the silence that followed Corrib’s completion, no post-project audit, security review, or forensic accounting, has only deepened suspicion that the system is designed to forget rather than to learn. A precedent felt reverberated through contemporary state expenditures in relation to the new Children's Hospital and various other infrastructure projects. Interestingly enough, the developer of said hospital, BAM Civil Ltd., was also directly involved in the Corrib Project, trading under the name Ascon.

Implications for Ireland’s Energy Future

As Ireland positions itself as a leader in offshore renewables and a potential exporter of green hydrogen, the lessons of Corrib are urgent and unresolved. Without a clear and enforceable framework for safeguarding critical infrastructure from strategic capture, be it corporate, geopolitical, or hybrid, Ireland risks repeating the mistakes of the past on an even larger scale.

There is still no national mechanism to assess the geopolitical risks of infrastructure development. Though a welcome development, the National Security Analysis Centre remains limited in mandate. Meanwhile, the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications has yet to produce a comprehensive review of legacy fossil fuel licensing decisions or to establish a transparent auditing process for past deals.

Towards Democratic and Strategic Clarity

Corrib should have been Ireland’s energy sovereignty success story. Instead, it revealed how easily state interests can be subordinated to opaque decision-making, political convenience, and private gain. The damage was not only financial, but also institutional and an affront to the democratic process for the benefit of foreign capital.

If Ireland is to confidently navigate the next generation of energy investment and infrastructure development, it must start with clarity. That means introducing constitutional protections for critical resources, establishing independent oversight for licensing and infrastructure decisions, and conducting a retrospective investigation into Corrib, not for punishment but for understanding.

The Corrib gas field is no longer just an energy project. It symbolises how a small state can be outmanoeuvred in its own sovereign territory and reminds us that true sovereignty requires more than rhetoric. It demands systems built for transparency, accountability, and resilience in the face of quiet but powerful forces.