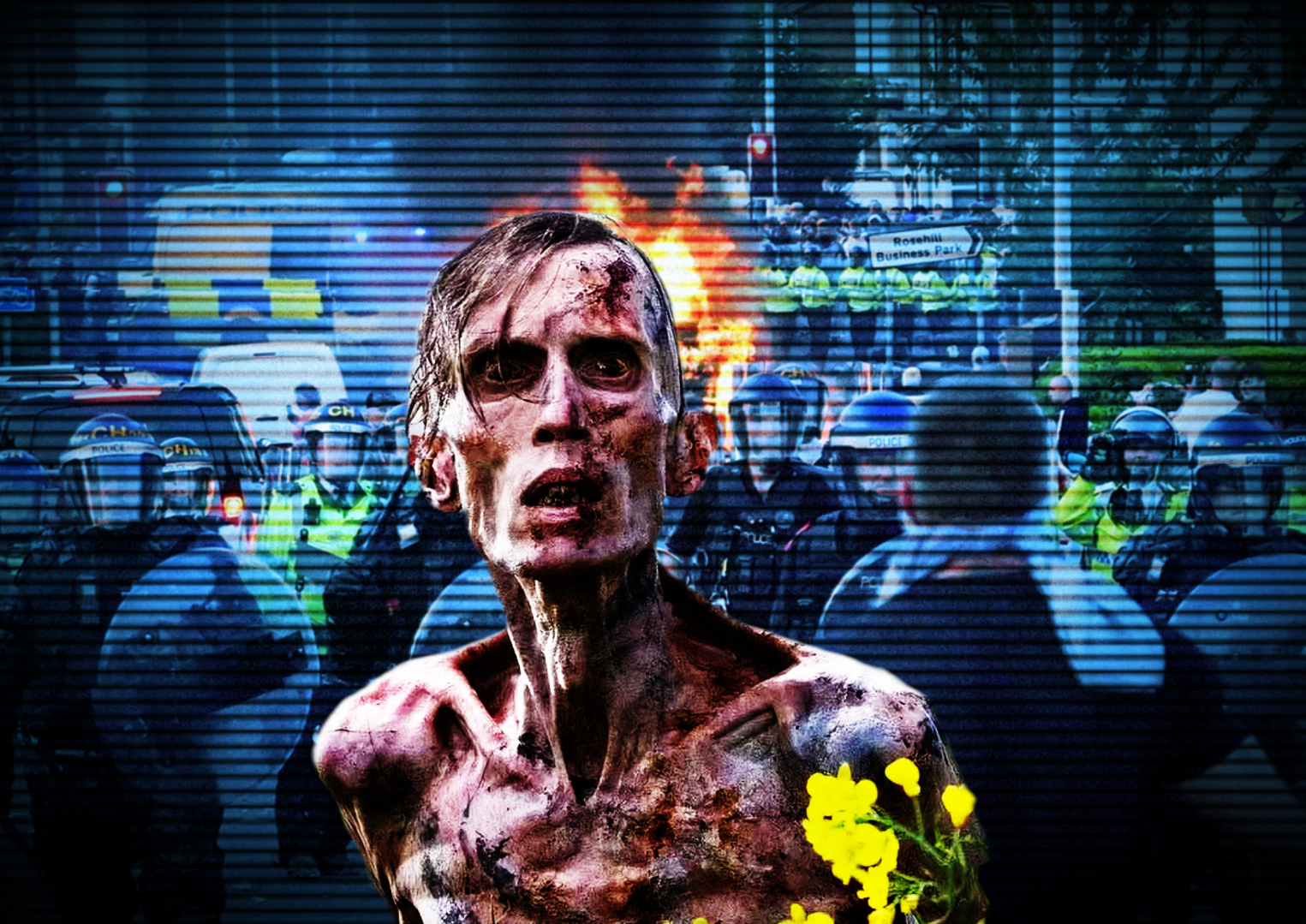

Does 28 Years Later Anticipate England’s Populist Turn?

A revival of a 2000s cult classic has become an unorthodox vehicle for a swipe at post-Brexit Little Englanderism.

The second instalment of 28 Years Later reaches Irish cinemas this week, a full quarter-century after Cillian Murphy first appeared on the silver screen amid a zombified Britain, reeling from the release of a bioweapon known as “Rage.”

Widely credited with helping to reboot the modern zombie genre, the original 28 films were less interested in gore than in atmosphere, channeling post-9/11 Western anxiety. 28 Weeks Later pushed this political subtext further, mounting a full-throated critique of the American occupation of Iraq via the motif of zombies.

Taken together, the 28 Series reads as a sustained critique of reactionary answers to civilisational decline that must be taken on the chin by the right, each instalment targeting a specific reflex of a collapsing order. Misogynistic soldiers sadistically attempting to enslave fertile women in the first; the American military complex managing nations under thinly veiled occupation in the sequel.

The latest instalment offramps from the franchise’s Bush-era critiques of American imperialism and instead centres on post-Brexit anxiety in a post-apocalyptic England. More than a quarter-century on, the English survivors are depicted as having retreated into a conspicuously homogenous Lindisfarne. The film itself is spliced with mockumentary style clips parodying British chauvinism; the film's directors unapologetic about the new instalment serving as an anti-Brexit parable, with both Britain (and Ireland, incidentally) sealed off from a Europe that has moved on.

While audiences fixate on the infected, the film’s messaging is unambiguous. The most obvious takeaway is that the island sanctuary functions as a less than optimal resolution to a long-running English crisis of identity; a crisis that is accentuated by mass migration.

To the point of parody, Brexit-era fantasies of sovereignty and control are pushed to their logical extreme by Boyle. Lindisfarne serves as a technique to demonstrate the consequences of isolation: the perpetuation of the familiar, albeit diminished, at the cost of endemic pettiness. This, for better or worse, is little England.

The second half of the film was released the week that the custodian of milky British conservatism, the Tory Party, received a major symbolic blow from Reform. The film gestures toward the future of Englishness within, and perhaps after, the mollifying civic constraints of the Union. One where Britain’s multinational and potentially multiracial settlement dissolves into ethnic-separatism — a prospect augured by Southport, the rise of Reform, and mass migration.

Danny Boyle appears fully aware that some form of English ethno-national consolidation is coming, not as a fringe BNP-style aberration, but as the path of least resistance once the UK’s post-imperial and post-union framework finishes eroding.

Boyle, more than most on the Right, seems to understand that even if ethno-nationalism becomes inevitable, it will not be exhilarating. For all the film’s unambiguous politics, even right-wing viewers are invited to notice the cost: this is what winning would be like.

Contrary to alt right basement dwellers, Lindisfarne isn’t a mythological ethno-state; it’s more akin to a besieged Belfast housing estate racked by sectarianism and ethnic myths.

While the second offering of 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple diverts its attention away from Englishness to wider meditation on religion and Christology, it drops all pretences in its final five minutes, finishing with a history lesson denouncing populism and the far right. Hardly subtle.

Yet overall 28 Years is honest enough to concede something more uncomfortable. If Britain dissolves as a shared project, if the UK continues to hollow out with migration, and if liberal pluralism loses legitimacy among the native English majority, then this stagnant end state may be the only avenue left for an English nation to persist at all.

For an Irish audience, the warning embedded in 28 Years Later lands closer to home than Boyle likely intends. Ireland is not England, but it is drifting into a structurally similar predicament.

The deeper lesson, then, is not to copy England’s retreat nor to double down on Ireland’s present course into progressive oblivion, but to recognise the shared civilisational bind we, as distinct peoples, find ourselves in.

Nations that refuse to think seriously about national continuity eventually find themselves choosing between bad options under pressure. In a critical, partisan fashion, 28 Years Later effectively imagines a future England selecting ethnic containment as the last workable form of nationhood. Ireland has not yet made such a choice, but the conditions that force it, mass migration being the most glaring, are already visible.

Both islands are running out of time to decide what kind of continuity they are willing to defend before stagnation and the invasive infected hordes make the decision for them.