Ealaín Nua-Aimseartha: Modern Art On Our Own Terms

Maitiú Ó Laoidigh

Believe it or not, I have recently discovered that not all modern art is bad. There are Irish modernists who can inspire the Right and can create a sense of Old Ireland and what it stood for.

Yes, these paintings are in a modern style but their message is not distinctively “modern” in all the worst ways and I think the right needs to get past only liking traditional art as there’s a lot more to them than taping a banana to a wall and calling it art.

Gerard Dillon: (1916-1971)

The first artist in question is Gerard Dillon. He was born in Belfast in 1916 to a strong Catholic and nationalistic family. He left school when he was only fourteen and worked as a painter and decorator for seven years. In 1936, he started out as an artist painting in a surrealistic and primitive style. Dillon was heavily influenced by the lifestyle led by Connemara natives, in particular a small town called Roundstone, enjoying many summers there.

He had his first solo exhibition in 1942 at the Country Shop, St. Stephen’s Green titled “Father, Forgive Them Their Sins”. In 1967, Dillon had a stroke, spending six weeks in hospital. After this, his work took a different path. His art became dream-like with mortality and death being his primary themes.

Two years later, he pulled his artwork from the Irish Exhibition of Living Art in Belfast in protest during the Troubles against the “arrogance of the Unionist mob”. On 14 June 1971, Dillon suffered a second stroke and died, leaving behind an array of interesting artwork which can be seen in many galleries throughout Ireland including the National Art Gallery.

“The Little Green Fields” is a painting I saw upon my first trip to the National Art Gallery a couple of years ago. I too had it in my head that all modern art was bad until I saw this. In such a simple way, Dillon brings together what Old Ireland stands for with its religious symbols, labour of the land, dry-stone walls, the horses, the thatched cottages, a dolmen, a sculpture of a monk, the ruins of an abbey, and a high cross. The style of the painting is similar to how they painted in Early Christian Ireland.

The second painting from Dillon is called “Island People''. This painting is similar to “Little Green Fields'' with its symbols of Old Ireland, again, inspired by the Connemara landscape. The man in the painting, most likely to be Dillon himself, looks like he is leaving the island of Inishlackan, a place where he lived between 1950 and 1951. He has a certain melancholy to him with his hunched posture as if he is sad to be leaving.

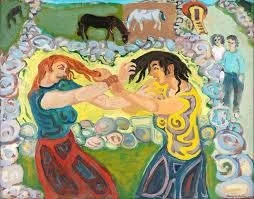

“Tinkers Fighting” is the name of the above painting and is a name that could get you into trouble nowadays (PC gone mad). We see Dillon’s beloved stone walls and horses in the background although this time the painting goes against its peaceful surroundings with two piebalds going at it while a couple feature in the background looking on in horror! The colours used jump out at us and signal a fiery energy between the two lasses.

“Village Church” takes on similar themes to Dillon’s works although it is painted in a darker colour perhaps signalling a funeral taking place inside. This one was not inspired by Connemara as the Church in question is St. Joseph's Church, known today as Hannahstown Parish, outside Belfast. The darker colour could also relate to how Dillon felt about Belfast, in general, compared to the West of Ireland.

I couldn’t find the name of this painting but I’d imagine it’s something like “Woman in Rain'' going by Dillon’s usual artwork titles. If you look closely you can see a pair of legs on either side of the woman taking shelter under her cloak from the downpour. We see more horses and stone walls giving it all the authenticity of the West of Ireland.

“West of Ireland Couple and Horses” does what it says on the tin. It’s a couple on a stroll with two beautiful horses in front of them. This time the horses take front and centre rather than being background LARPers. The colours used to paint the sky stand out with what looks like the sun setting going by the calm mood of the painting.

“Connemara Lovers” gets an honourable mention. This would look good on a St. Valentine’s Day card for all you fakecels out there.

Daniel O’Neill: (1920-1974)

Daniel O’Neill was also born in Belfast a few years after Dillon in 1920. He started off as an electrician and was mostly self-taught when it came to art. He was an expressionist romantic painter focusing on similar themes to Dillon such as religion, rural Ireland and death. He started his painting career as World War II began and after the Belfast Blitz in 1941, he salvaged some wood and experimented with wood carving. In the same year, O’Neill had his first exhibition at the Mol Gallery in Belfast.

An influential Dublin dealer called Victor Waddington spotted O’Neills talent and his support allowed O’Neill to give up his trade so he could focus on his artwork. In 1949, he took a trip to Paris and was hugely influenced by the artists he was introduced to there. During the 1950s, O’Neill moved to Conlig, Co. Down from Belfast where there was a small artist’s colony forming which included Gerard Dillon. After the closure of Victor Waddington’s gallery in Dublin, O’Neill struggled financially. He moved to London in 1958 where his work became bleak and gloomy (the London effect). He moved back to Belfast in 1971 and died in 1974. His art can be seen in the Ulster Museum and the Hugh Lane Gallery amongst others.

The name of this painting is “Gethsemane” which is where Christ went through the agony in the garden and was arrested before his crucifixion. O’Neill does an excellent job of showing the pain in Christ’s face and the sweating of His blood.

This next painting is of St. Joseph and is simply titled as such. It was exhibited at The Ashley Gallery, London in the 1950s, which showed religious works by contemporary artists.

O’Neill was deeply affected by the Belfast Blitz. This painting called “The Storm” shows a young boy with a horse fleeing from a ruined house in a desolate landscape reminding us of O’Neills younger years as an artist when he salvaged timber from bombed houses to experiment with wood carvings. The mood is dark and the red on the horse signals danger.

“Donegal Couple” is a lovely painting of a couple from, you’ll never guess, Donegal wearing traditional Irish garments, something O’Neill was well known for. An art critic called T.P. Flanagan once described them as "those timeless garments the painter created for his characters".

O’Neill visited North Donegal regularly in the late 1940s and early 1950s and even went with Gerard Dillon during the summer of 1947. His favourite part of Donegal was Rathmullen and he painted many views around the area such as a summer and winter view of Knockalla, seen above. The paintings are called “Knockalla Hills” and “Snow Scene at Knockalla”.

In O’Neill’s later years, his paintings became brighter and more vibrant. This one is called “Figure in a Landscape” and I dare say it could be Ireland’s answer to the Mona Lisa. Her smile is quite similar and adds to the mystery of the painting. The garments and landscape remind us of Old Ireland.

Charles Lamb

The next painter I am going to look at is Charles Lamb. He was born in Portadown, County Armagh on 30 August 1983. His father was a painter and decorator with Lamb serving an apprenticeship under him. He studied life drawing at the Belfast School of Art and in 1917, he won a teaching-scholarship for the Dublin Metropolitan School with Seán Keating being his tutor. While studying there, Lamb became friends with the Galway writer, Pádraic Ó Conaire, who persuaded him to visit the West of Ireland and like Dillon, he fell in love with it, in particular a place called Carraroe in the Connemara Gaeltacht.

He first visited here in 1921 and described the place as having a “National essence”. In 1922, he travelled a lot around Ireland to try and finalise his landscape style, going to Kent, Down, Donegal and Waterford and even voyaged to Brittany where he found many similarities to the West of Ireland.

A year later, he had his first solo exhibition at the St. Stephen’s Green Gallery where he presented landscapes from Carraroe and the West of Ireland. From 1926 to 1928, he divided his time between a caravan on the Aran Islands and a house in Brittany. His paintings started to gain attention globally and in 1928, he had an exhibition in Boston then in New York for each of the following two years before exhibiting in London in 1931.

The Summer Olympics of 1932 took place in Los Angeles with Lamb being one of 541 artists from 31 countries competing where he showed “A Galway Fisherman”. He also competed in the 1948 Summer Olympics. Lamb built a house in his beloved Carraroe in 1935. Just before World War II started, he spent the winter of 1938 to 1939 in Germany (make of that what you will). In 1949, Lamb illustrated for Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s book Cre na Cille, often regarded as one of the best Irish language novels. On 15 December 1964, Lamb died at his home in Carraroe. His works can be seen in the Ulster Museum, Hugh Lane Gallery, and the National Art Gallery.

“Bean an Drochshúil” (The Woman with the Evil Eye) is perhaps the Banshee of Carraroe? Whatever you do, do not zoom in on this woman’s eyes. The colours used give it a sinister feel and the atmosphere looks stormy. The woman is also armed with two canes to batter anyone who looks her way.

Boats were a popular object painted by Lamb and “Carrying the Currach” shows a sense of comradeship with a group of lads carrying a boat after a fishing trip. There is a bright, summer feel to this painting with even the men dressed in light colours.

Here we see Lamb painting his cherished Carraroe cottages with the painting simply titled “Cottages Carraroe, County Galway.” The swirls give it that dream-like almost drunk feel or if you’re someone like me who has very bad eyesight, it may remind you of your vision without your glasses. It looks like a calm summer evening going by the colours used.

This one is quite humorous as at first glance it looks like someone riding a horse but it’s actually titled “Old Woman Driving Cow.” There is a gloomy, dark feel to it with Lamb using darker colours, something he didn’t usually do when painting the West of Ireland.

In this painting named “People of the West” we see the faces that let you know this is Lamb’s work. It’s bright and cheerful but at the same time I wouldn’t mess with these women.

Jack Butler Yeats

Last and certainly not least is the most well known artist out of the four I’ve discussed, it’s Jack Butler Yeats, brother of W.B Yeats. He was born on 28 August 1871 in London although he grew up in Sligo living with his grandparents before returning to London in 1887. He studied art at the Chiswick School of Art. He started off as a cartoonist and only began to work with oils in 1906, painting in an expressionist style.

Yeats was profoundly inspired by the Irish Civil War, his biographer, Hilary Pyle wrote “Yeats’s patriotism was intense and of a deeply idealistic nature”. “To him the Free Staters were middle-class, while the Republicans represented all that was noble and free”. Like the other artists mentioned, he enjoyed painting the Irish landscape and in particular, horses, which he believed represented complete freedom. He was the first to sell an Irish painting for over £1 million, the painting in question being “The Whistle of a Jacket”. Similar to O’Neill, Yeats worked with Victor Waddington and he was his sole dealer and business manager. At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Yeats won a silver medal in the arts and culture segment for his painting “The Liffey Swim”. This made him the first Olympic Games Irish medalist since the creation of the Irish Free State. He died in Dubin in 1957, leaving behind many unique paintings which can be seen throughout Ireland in both public and private settings.

First up is “Liffey Swim”, this is the painting that won Yeats and Ireland silver at the 1921 Summer Olympics. It depicts a Dublin annual sporting event that has been running since 1920. Yeats painted himself into the painting and is the man with the brown fedora. There is a feeling of excitement coming from the painting with the spectators trying to get a glimpse of the swimmers going past.

“A Summer Evening, Rosses Point, 1922” depicts a summer evening in Sligo where Yeats spent most of his youth. There is a lucid, carefree element to the painting and it looks like the ladies are having a dance while the men shoot the breeze.

Titled “Early Morning, Glasnevin” and painted in 1923, this was the year Dublin was described as the city of funerals due to the ongoing civil war. It’s not known who the deceased was but given that Michael Collins was shot and buried in Glasnevin a year earlier, it’s possible it’s his funeral being depicted.

Here we see Yeats painting his beloved horses with a man with his hands clasped singing to the heavens. The artwork is appropriately titled “The Singing Horseman”. There’s a wild, radiant energy coming off the painting, almost like the horse is about to throw off its rider. In a letter of 1952, the artist said “I got a thrill out of man and horse when I painted them”.

“The Poetic Morning” is probably the most modernist, for lack of a better description, painting I’ve looked at in this article. It’s rich in colour and the warm reds and yellows reflect the warmth and pleasure of the sunrise. The conical peak visible in the background resembles Croagh Patrick.

I hope you enjoyed the art I’ve shown throughout this article and that it has given some food for thought when it comes to modern art. The right is in need of contemporary artists and the only one I know of is Immanuel Godson. Maybe this article will inspire some of our artists to come out of the woodwork!