How the World Turned Ugly: the Historical Demise of Beauty as a Value

This article was originally published on Red Rose’s Substack and is syndicated with the permission of the author.

Beauty, once held among humanity’s highest values, has been degraded in the modern age to a meaningless concept, resulting in a rather ugly reality. Utilitarian and profit-driven logic have systematically negated aesthetic considerations across all areas of life. Grand cathedrals and ornately decorated buildings have given way to soulless, brutalist constructions governed by purely functionalist principles, while traditional craftsmanship has been replaced by mass-produced, disposable goods. Art, once considered among life's most essential pursuits, has been relegated to a futile hobby. Historically, beauty was understood as a bridge between the transcendental and physical world, a means of drawing humanity closer to truth, goodness and the divine. Over time, however, this understanding gradually faded. Our unsightly modern environment both reflects this spiritual alienation and perpetuates it, signaling a profound philosophical shift in the way beauty has been understood and valued over time.

Beauty as truth, goodness and the divine

Dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica, photo by Harold Wainwright

Throughout most of history, beauty has been pursued as an end in itself (telos), something to emulate in clothing, architecture, art and life and one of the highest goods to attain. The ancient Greeks materialised their regard for beauty (kallos) through complex sculptures and decorative temples, poetry and music. Beauty touched every aspect of life, from politics and religion to personal virtue. To the ancients, beauty surpassed mere aesthetic gratification, and was linked to moral excellence. It was seen as a reflection of the ultimate good and the divine, a link between the physical and the transcendental. Temples were constructed according to the Golden Ratio, reflecting perfect harmony and balance, and sculptures were perfected to the ideal human form.

It was Plato who argued that beauty is intrinsically connected to truth, goodness, and the divine. According to his philosophy, the physical world is merely a shadow of the higher, perfect realm of Forms. Cultivating love of beauty promotes virtue and wisdom as it brings us closer to this ideal, perfect realm. Reason and contemplation are required to discover beauty, and the ultimate good, not just sensory experience. Although Aristotle did not share Plato’s concept of an ideal world of Forms, he nonetheless assigned beauty an equally important role. For Aristotle, beauty is a reflection of harmony, proportion, and order. It plays a vital role in guiding individuals toward the flourishing life or highest human good (eudaimonia). In this sense, beauty is essential to understanding and achieving the ultimate good. The Romans later inherited the Greek aesthetic tradition, which then gave way to Christianity’s view.

Christianity has long held beauty in high regard, viewing it as a means of expressing the divine and drawing the soul closer to God. The beauty of creation was seen not merely as aesthetic but as a reflection of God's glory, order, and infinite wisdom. Just as truth and goodness are considered manifestations of God, so too is beauty. Even in the Middle Ages, often wrongly labeled ‘the Dark Ages’, beauty was of crucial importance to religion. Medieval churches were adorned with intricate frescoes, stained glass windows, illuminated manuscripts, and sculptures, all designed to lift the mind and spirit toward the divine. Christian saints and mystics frequently described beauty as a spiritual force that stirs the soul toward holiness and contemplation of the eternal. This theological understanding of beauty echoes Plato’s conception of the world of Forms, in which earthly beauty is a reflection of a higher, perfect reality. Friedrich Nietzsche captured this connection by describing Christianity as "Platonism for the masses," highlighting its philosophical roots in classical thought.

From sacred ideal to commodity

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, photo by e55evu via CanvaPro

The protestant reformation in the 16th century challenged the importance of beauty in religion. Beauty was condemned as vain, a distraction from the word of God, and a way for the papacy to enrich themselves. Churches were raided, statues demolished, and religious portraits defaced. Large parts of Europe embraced this new form of Christianity, in which aesthetics no longer held a significant place. As a result, beauty ceased to be a shared ideal across the continent. This shift opened the door to religious pluralism and skepticism, developments later amplified by the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. Without a common belief in a transcendent ideal or higher purpose, beauty loses its meaning. The great cathedrals, constructed over generations, stand as monuments to a collective faith in something beyond individual lives. Yet, as belief in the transcendental waned, beauty, nature, and mystery were increasingly supplanted by science, calculation, and measurement.

Inspired by the ideas of the reformation and the ideas of the Enlightenment, beauty increasingly came to be associated with the luxuries of the elite. It was used by the papacy, kings and rulers as a display of wealth and power. Over time, beauty came to symbolise not universal value but social inequality, reflecting the divide between the privileged and the impoverished. As the French Revolution erupted later that century and egalitarian ideals gained momentum, resentment toward such ostentatious luxury grew. While the upper classes indulged in extravagance, many people in the countryside faced starvation. The revolutionaries targeted these symbols of luxury rather than the concept of beauty itself, as it had been understood by the ancient Greeks, Romans, and early Christians. True beauty was historically accessible to all social classes through public spaces, religious art, and skilled craftsmanship, not just luxury goods. The notion that beauty was a value equally accessible and important to all, regardless of social status, had by this time been buried deep in the historical collective unconscious. And so, the rebels stormed the Bastille demanding liberty and equality for all–but forgot to add beauty to the list.

During the Enlightenment, the ideas of moral and aesthetic relativism gained significant traction. David Hume, a central figure in this shift, argued that there are no objective moral or aesthetic values; rather, moral judgments vary across cultures, historical periods, and individuals. In his view, value resides in the eye of the beholder. Immanuel Kant also emphasized the subjective nature of beauty, focusing on personal experience and individual judgment. However, both philosophers acknowledged a challenge: if beauty is understood solely as subjective experience, it loses its capacity to serve as a universal or meaningful value. In this case, beauty risks being reduced to mere amusement or pleasure, lacking the deeper significance associated with truth or goodness. To reconcile this, they suggested that a lasting consensus of taste might provide a foundation for a more objective aesthetic standard. Despite this side note, aesthetic relativism ultimately emerged as the dominant perspective. Without objective beauty and a shared aesthetic ideal, beauty became a private rather than a public concern.

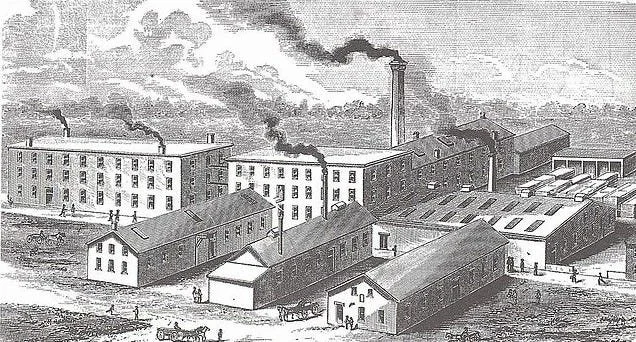

Another blow to beauty came with industrialisation in the 18th century. Until that time, products were the result of skilled craftsmanship. Craftsmen specialised in trades such as furniture-making, tailoring, or metalwork, creating goods that were labor-intensive, crafted with care, and made from high-quality materials often built to last for generations. However, the inventions of the 18th century transformed production methods completely. Handiwork was replaced by machines powered by steam engines. Textiles were no longer woven by hand but produced on spinning jennies and power looms. Goods were manufactured on a scale never seen before, causing many craftsmen, such as weavers and blacksmiths, to lose their livelihoods. High-quality, handmade products gave way to mass-produced items. Industrial processes prioritised efficiency and uniformity at the expense of uniqueness, individual skill, and beauty.

Though capitalism had existed since the 17th century, the Industrial Revolution put it on steroids, massively intensifying its growth and impact. The destructive aesthetic consequences of capitalism became impossible to ignore. Making profit became the main focus. With value being measured solely in economic terms, anything else loses its value. Capitalism transformed cities into functional, aesthetically impoverished environments. Rather than a source of sublime beauty, nature became a resource to be exploited. Under capitalism, “beauty” now merely signified the luxuries that the bourgeois attained through the wealth gained from the system. Beauty was no longer reflective of some higher purpose or moral value, but purely a commodity.

Resistance grew when the destructive aesthetic effects of capitalism became clear. Two notable individuals were John Ruskin and William Morris, who criticised the industrial age for producing ugliness, both in physical environments and in human labor. They argued that mass production destroyed the aesthetic and spiritual value of craftsmanship. Ruskin saw industrialisation as morally and aesthetically corrupting, while Morris, a craftsman himself, saw the degenerating effects that the industrial process had on craftsmanship. Believing that craftsmanship embodied not only aesthetic excellence, but also moral and social value, Morris sought to restore dignity to labour and beauty to everyday life. This conviction led him to found the Arts and Crafts Movement, which aimed to revive traditional techniques, elevate the role of the artisan, and reintroduce beauty into domestic and public spaces.

While John Ruskin and William Morris were articulating their critiques of industrial society and championing a return to craftsmanship and aesthetic integrity, a parallel cultural movement was gaining momentum across Europe: Romanticism. Emerging in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Romantic movement in visual art, literature, and music arose in direct reaction to the values of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution: mechanisation, mass production, the dehumanising effects of capitalism, and the scientific reduction of nature. In contrast to these forces, Romanticism sought to reclaim a sense of beauty, wonder, and spiritual depth in a world increasingly dominated by machines and markets. Central to the movement was the idea that beauty and truth are not solely accessible through reason or science but through emotion, intuition, and a deep connection with nature. Romantics celebrated the sublime: the awe-inspiring, sometimes terrifying power of nature. By elevating individual experience and emotional response, Romanticism offered a powerful counter-narrative to the impersonal rationalism of its time, insisting that the soul, imagination, and aesthetic experience were vital to human flourishing.

Unfortunately, by this stage, beauty was too far gone to be saved, as the ideas of another philosopher gained prominence. Jeremy Bentham introduced the utilitarian theory, which was later expanded by John Stuart Mill. This idea promoted the principle of “the greatest happiness for the greatest number”, which implied that objects and actions should produce utility by maximising benefits in terms of happiness and well-being. To determine what contributes most to overall happiness, actions needed to be measured and made quantifiable. Since beauty is an unquantifiable value, it was largely disregarded within this framework and the primary focus shifted to efficiency.

Modernism and the aesthetic void

The national theatre in London, photo by Altaf Shah

Around the same time as Bentham and Mill published their work on utility, the art world witnessed a profound shift. Up until the 19th century, art was guided by structures, rules and regulations. There were rules guiding perspective, colour theory, realism, and ideas of a higher ideal. Impressionism is often seen as the first modern art movement, which started to play around with the academic rules of art. Rather than depicting scenes as they were, artists like Claude Monet, and later Vincent van Gogh, started to paint scenes as they were perceived. However, although impressionism and later post-impressionism challenged style, they did not challenge form. They continued to paint depictions of the real world, painting landscapes, portraits and everyday things.

A more clear and radical break, and a definite transition into modernism, came in the 20th century with the emergence of Cubism, Expressionism and mostly, Dadaism. These forms of art challenged all traditional rules and abstracted art, focusing on personal experience and emotions over reality. Dadaism was the most extreme form, it was complete anti-art. It challenged the idea that art needs to be beautiful or the artist needs to be skilled. Being disillusioned with industrialisation and the destruction of the first World War, it embraced absurdity and nihilism, and carried a strong anti-bourgeois sentiment.

In architecture, an architectural movement emerged from the same philosophy: Bauhaus, a German art school that focused on function and mass production. Characterised by minimalism, geometrical shapes and the idea that “form follows function”, it became one of the most influential art movements in modern design and architecture. Later in the 20th century, these ideas where echoed in functionalism and brutalism. Dressed under the disguise of “egalitarian ideals”, it was made for the masses by symbolising honesty and transparency. It meant the ultimate death for decoration and aesthetic consideration in architecture. Capitalists and neoliberal governments eagerly embraced these new modernist principles. Buildings could now be constructed as cheaply as possible, without costly decorative elements or even paint. Governments could erect a few bleak concrete blocks and call it a city hall, while real estate developers build grey, soulless apartment blocks under the pretense of cheap housing. The profit-driven capitalist mindset began to permeate every aspect of society, and continues to do so today.

The rise of mass consumption and mass media in the late 20th century replaced high-quality art with mass-produced pop culture. Culture has become a degenerative slop of nothingness as "high" art forms like painting or classical music are dismissed as an elitist business. Teenagers are discouraged from pursuing artistic careers because “it doesn’t pay.” Dress sense has become dominated by mass-produced, cheap, low-quality leisure wear made by children in third-world countries. Hardly anything holds value: products rarely last longer than a year. A Google image search for beauty shows only photoshopped images of women covered in makeup: it seems like in modernity, a Kardashian has replaced Botticelli’s Venus. In the modern age, the concept of beauty has become entirely meaningless – leaving a spiritual void in an increasingly unappealing world.