Ireland’s National Genesis

Ireland hasn’t been the same since the Dublin riots.

All has changed, changed utterly since that fateful night.

But has a terrible beauty been born?

Or have vainglorious louts engaged in a sacrifice too long?

The billowing smoke that engulfed the city that night, with the Great Liberator looking on gallantly, saw the proles of inner-city Dublin express years of frustration and a sense of betrayal, with an assortment of marauding groups desecrating shopfronts and burning public transport.

The casus belli which was the stabbing of three children would do that to people.

If your own kids cannot walk the streets during the day, outside a school no less, without the fear of getting butchered by the sharp edge of a knife - what have you got to lose?

The spectre of a foreign national - his nominal Irishness, courtesy of citizenship granted in 2014, merely adds insult to injury - committing the grievous act only intensified the rage of a forgotten underclass.

When you invite a guest into your home and that guest proceeds to attack members of your household, the homeowner may be liable for negligence resulting from an attack that could have been prevented.

A nation is such a home. And a guest, whose presence owes to the indiscretion of a lackadaisical political class, who proceeds to mercilessly attack a nation’s inhabitants is held to a different standard.

This is not due to a sense of superiority held by those within a household or nation relative to outsiders; rather it’s an acknowledgement of the special bond shared by those within its walls or boundaries.

Following the carnage in central Dublin, a discussion and debate around immigration levels into Ireland, that had been stirring up with the advent of both rural and urban migrant protests in months hitherto, descended into an international discussion on contemporary Irish identity with historical reference.

British Journalist Daisy McAndrew, speaking on Talk TV the day after the riots, said that the headline ‘20 per cent non-native population within Ireland’ was “huge”, adding that the figure is “higher than the immigration into America… when it was a melting pot for immigrants all over the world.”

American political strategist Steven Bannon, appearing on Tucker Carlson’s show on X, stated:

“You're seeing a natural blowback and you're really seeing it among working-class people in the cities, Irish nationals, Irish citizens, whose family have been there for generations and generations and generations and have nothing to show for it.”

Ironically, Comedian Russell Brand added the most depth and nuance to the discussion when he stated that Ireland had a very “particular” history, with “ethno-nationalism a necessary part of their defence against an external oppressor”.

Thus, the lazy invective of racist is not applicable to the Republic’s assertion of autonomy amid detached globalism, Brand asserted.

Far from being the sole view held by a polemical comedian, the renowned Irish economist David McWilliams mentioned years prior in The Generation Game:

“Given that Ireland struggled for independence in order to create self-rule for the Irish, the State’s foundation is ethnocentric.”

Emma Dabiri, in The Guardian, took issue with these sentiments, writing that the attempt to “position Ireland as somehow existing outside of global events” is a “weird flex bro” - prose par excellence.

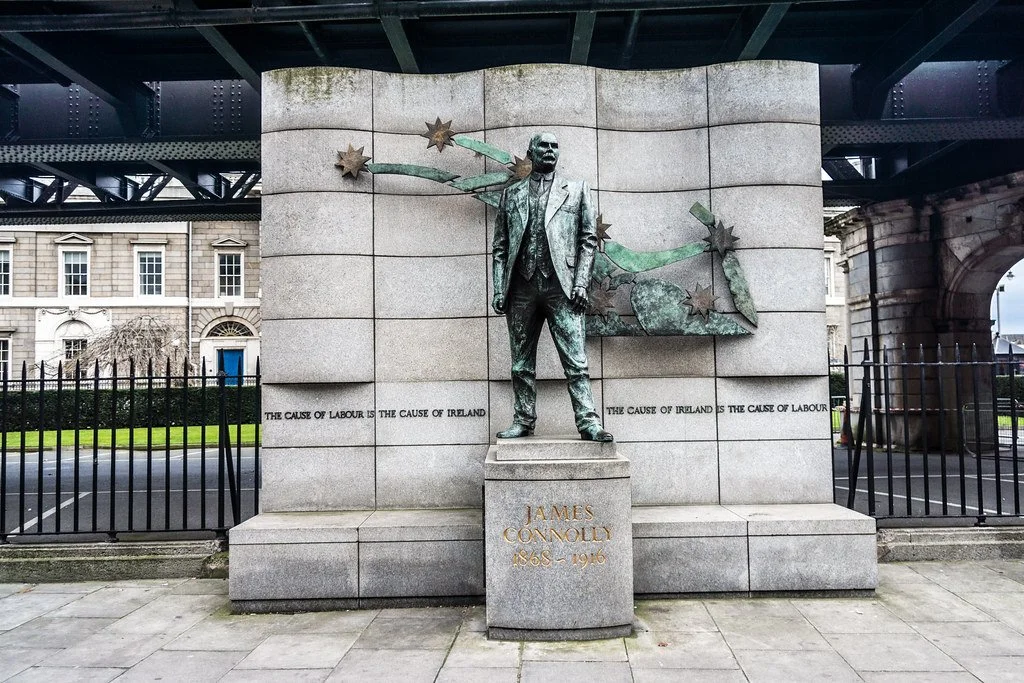

Dabiri attempted to rewrite Irish nationalism, turning it upside down to fit her own twisted ideological frame as “a rejection of ethnicity or blood as the basis for self-determination” - to buttress this contention, Dabiri pointed to the worldview of the United Irishmen of 1798 and the Irish Citizen Army’s James Connolly.

Her perverse interpretation of historic Irish nationalism makes sense if you look at it from a purely egalitarian prism.

Often, left-wing proponents of Ireland’s struggle for nationhood believe such a struggle began in 1798; for the left, the French revolutionary-inspired, Belfast-born movement was the quintessence of our centuries-long fight.

Indeed, from their point of view, the only signatory to the 1916 Proclamation worth remembering and reflecting upon is the Marxist James Connolly - whose ideology was a lot more multifaceted and identarian than contemporary Marxian exponents appreciate.

The valiant struggle of Red Hugh O’Donnell and Patrick Sarsfield, in which Catholicism held a centrality, or Padraig Pearse, whose explicit ethno-nationalism mixed with transcendental belief, are airbrushed away.

The Irish struggle has descended into a petty tug of war between political extremes: Traditional Catholics who assert Jacobite precedence; Marxists, for whom the Starry Plough supersedes; and rightists, whose worldview can be summated by the phrase “Ireland for the Irish”.

The truth is more complicated. Irish nationalism is nuanced, infused with a mixture of belief systems, with the contemporary Americanised culture wars unable to grasp the multifaceted nature of its particularities in resistance to English rule.

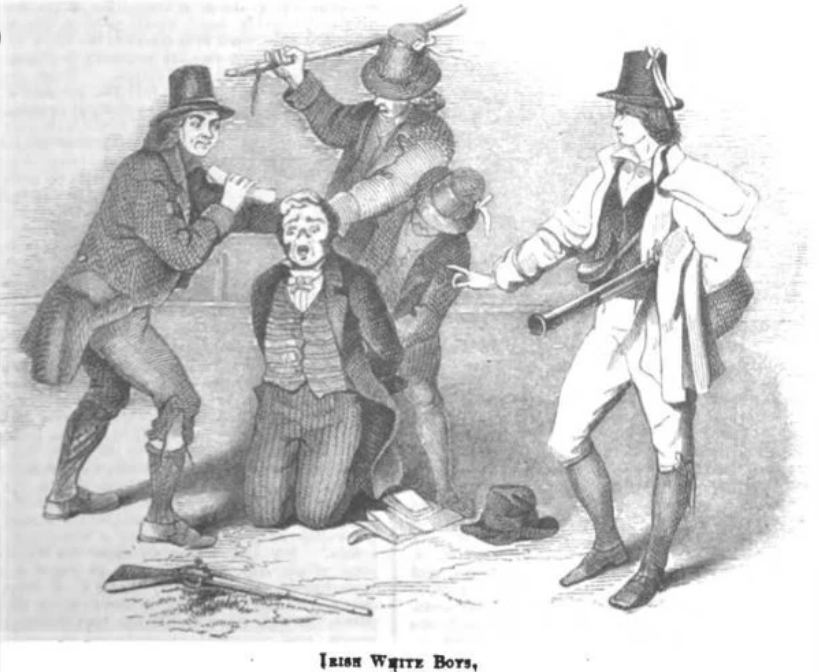

The Irish struggle is a hybrid struggle that involved a synthesis of various ideologies with ethnic assertion, religion, land ownership, and the rights of labour all manifesting into the expression of an Irish identity distinct from England.

In terms of its roots, Irish nationalism is a fusion of the disgruntled Gaelic Chiefains’ defence of their land rights and the ambitions of a Catholic Royal House in Spain and, paradoxically, England, the latter usurped by the Principality of Orange’s coup.

The Gaelic order, which the Earl of Tyrone Hugh O'Neill nearly managed to save, was distinct in a cultural sense and internationalist as it sought an alliance with continental Catholic power centres against English interests.

Ireland's two greatest allies were Catholic Spain and the egalitarian French Directory, with O’Neill and Wolfe Tone, respectively, beginning that Irish nationalist tradition of turning to gallant allies in Europe.

Land and power were the prime vectors of revolutionary zeal with Catholicism providing the glue.

Clerical power was instrumental to both the O'Connell Catholic emancipatory and land league campaigns, respectively. Alas, Puritanical clericalism would result in the coup de grace of the uncrowned king of Ireland, Charles Stewart Parnell, due to his love affair with Kitty O’Shea.

A Catholic middle class birthed by the ultramontanism of Cardinal Paul Cullen, whose idiosyncratic aversion to Fenianism but lust for nationalism, created an army of Christian brothers - a prelude to the young learned soldiers who would play a role in the Easter Rising, educated at Pearse’s Saint Enda’s.

Connolly’s struggle against the capitalist class that subjugated Ireland in general, and the proletariat of Dublin in particular, was a version of nationalism expressed through a workers’ revolt.

Ireland, he said, must be:

“ruled, and owned, by Irish men and women, sovereign and independent from the centre to the sea, and flying its own flag outward over all the oceans.”

This and Pearse’s assertion that “Ireland belongs to the Irish”, an expression atomised in today’s culture wars, were potent expressions that set the stage for the onslaught on April 24 1916.

While Pearse’s ethnic-basis for Irish nationhood derived from an acknowledgement of the existence of the Irish as a distinct and marginalised people, his utter aversion for the mercantilist British empire qua empire, that had in the past raped and pillaged and in the present forced Irishmen to their deaths in the Somme, was omnipresent in his writings.

In the ‘Sovereign People’, Pearse states:

“The nation is the family in large; an empire is a commercial corporation in large. The nation is of God; the empire is of man - if it be not of the devil”

In his essay ‘Ghosts’, he meditates on national freedom:

''Like a divine religion, national freedom bears the marks of unity, of sanctity, of catholicity, of apostolic succession. Of unity, for it contemplates the nation as one; of sanctity, for it is holy in itself and in those who serve it; of catholicity, for it embraces all the men and women of the nation; of apostolic succession, for it, or the aspiration after it, passes down from generation to generation from the nation's fathers'', Pearse eloquently posits in Ghosts.”

Ireland today is anything but the ideals as set out by the Gaelic Chieftains and the men and women of 1916.

Immigration is a symptom of a wider void in contemporary Irish identity.

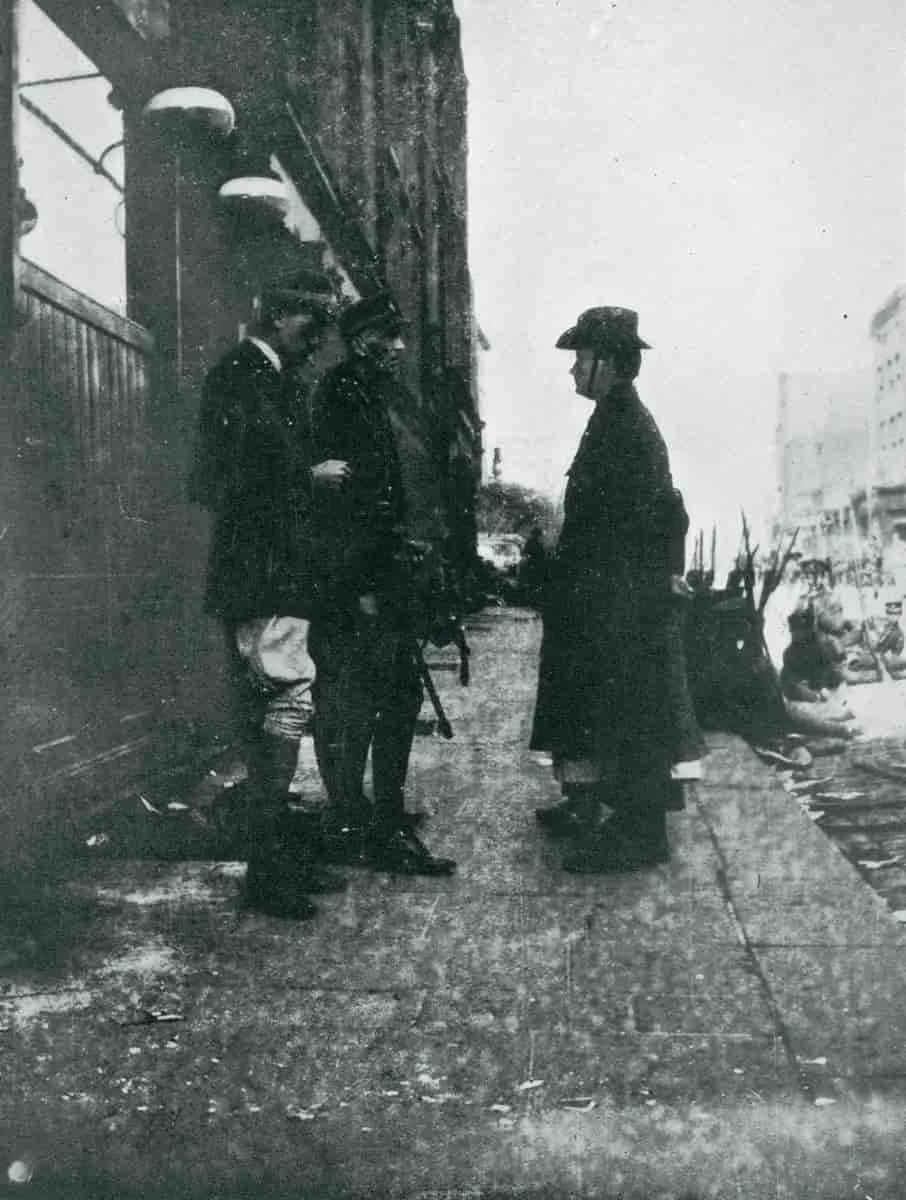

A virulent expression of Irish identity presented itself on the streets of Dublin in April 1916 and October 2023, with the latter being less organised and more sporadic growing out of a sense of desperation.

Despite the opportunistic and gratuitous nature of the riots, it has evoked a conversation on what the Irish nation is or ought to be.

Let us settle that question before society goes awry once more.

Let’s begin by appreciating its diversity of expressions.