Unveiling Louis Ferdinand Celine: Existentialist? - Part 1

This is the first part of a two part essay on the worldview of the French writer Louis Ferdinand Celine - the second part will follow in due course.

“Bonjour, Ferdinand. I don’t hold it my duty any more to run a chronicle of French publications, but I still know a real book when I see one, whatever the contents. Ferdinand has GOT down to reality, Ferdinand is a writer. Next one will be the last one. Gnrr, gnrrn, gnrrn, gnrr. Suicide of the Nation. La prochaine sera la derniere. Gnieres!” - Ezra Pound

“I am the armed wing of the little old ladies,

Of the blond angels with goggles,

Of the producers of wine,

Of the pure products of a common Spring.” - ‘Casse, Pêches, Fractures et Traditions’, Peste Noire“But we knew immediately that we always understand: this book is one of the finest refractory books of our literature. Our writers have always been bourgeois: it was the bourgeois Hugo who wrote Les Misérables. Vallès, the authentic rebel, is nothing next to Céline” - Robert Brasillach

Introduction

“Are you for or against those who are going to hang me?” – Letter to Jean Cocteau, Louis Ferdinand Celine

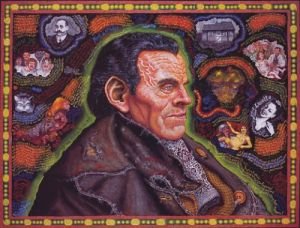

Louis Ferdinand Celine’s oeuvre has engendered manifold interpretations. Critics have profited from proffering their contribution to the on-going inquisition of his legacy. Celine is a succulent choice for the would-be critic to aim his sights at. A giant of French literature in the 20th century, indubitably, Celine was the devil to many, and for a select few a secular prophet.

Beyond the controversy which his name echoes, and in turn the pecuinary reward for his posthumous skewering, for an honest, bona fide critic, Celine’s literary-intellectual-biography offers numerous vantages points from which to tease out fruitful conclusions.

Even to his allies, Celine was enigmatic. The polycentrism of his life and worldview, and the ostensible contradictions therein, compounded with the unexpected virulence, rather than ironic detachment typical of a dallier in ideological extremity, with which he expressed his convictions, spurred jarred and confused reactions amongst erstwhile benefactors.

Celine donned numerous masks: anonymous writer, salacious womaniser, outspoken racialist, critic of French chauvinism, socialist, ardent pacifist, conspiracy-monger, League of Nations surgeon, and proto-existentialist – perhaps his vagrancy should take first place?

To say that Celine donned masks is fitting on more than one level. The name Celine itself is about as inauthentic as the cognomen ‘Ferdinand Bardamu’ – the protagonist of ‘Death on Credit’ and ‘Journey to the End of the Night’. Celine’s real name was Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches; ‘Celine’, the name fated to be his denominator, being the penname ascribed to ‘Journey to the End of the Night’ – the novel that skyrocketed his renown in France.

Given the autobiographical qualities of the above-mentioned works, who can say whether Destouches, the proud veteran and surgeon, Celine, the author and anti-semite, or Bardamu, the itinerant nihilist and coveter of ballerinas’ gams, is the genuine article?

Has anyone ever posited, in good faith, that we approach our mundane 9-5 gig unmediated by convention’s death mask?

Discerning what lay beneath the mask is the task of this essay.

Sartre Was a Garda Rat! Celine: An Existentialist?

“What are you hoping for? That they murder me! It’s obvious! Here! Let me squash you! Yes! . . . I see his photos, those bug eyes . . . that hook . . . that slobbering leech . . . he’s a cestode! What won’t he invent, this monster, so that they assassinate me! Barely out of my caca and he denounces me!” – ‘To the Nutcase’, Louis Ferdinand Celine

Celine is viewed as a progenitor of the existentialist vogue in Western literature. Notwithstanding the innumerable precursors to existentialism, there is weight to this contention.

Journey to the End of the Night is plagued by quips and quotes about death, the prospect (treated as a certitude) of our non-existence, and the fate of our prospective cadaver as maggot food.

In many respects, existentialism signifies the return of the personal to the foreground of western thought. It is truly a mark of the efficacy of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle’s philosophical endeavours, – not to imply that speculative philosophy was without antecedent spokesmen (Parmenides et al. of the Eleatic school) – that speculative philosophy triumphed over practical philosophy – stoicism, for instance – as the West’s dominant philosophical disposition; the millennia reign of Confucianism in China, an outlook that not even Maoism successfully repressed, represents the inverse outcome.

Earlier authors that adumbrate existentialism include: Kierkegaard, Pascal, Nietzsche, and Dostoevsky - 3 Christians, albeit of divergent strands, and an anti-Theist (not to be confused to with Atheism).

In the case of Kierkegaard and Pascal, their world had been unmoored from the unity of Faith and Reason that characterised the purview of the Medieval Church. Both men found themselves aligned with contextually heterodox theological standpoints - Pascal was a Jansenist; Kierkegaard was at odds with the Caesaropapism of the Church of Denmark

Dostoevsky’s ‘Underground Man’ was fashioned in a Russia assailed by social radicalism and atheism; the fathers of the radicals, the liberals, were effete Francophiles. Despite Russia’s otherness vis-à-vis the West, Enlightened Absolute Monarchs, such as Peter the Great and Catherine the Great, emerged, and precipitated the westernisation of Russia.

With an antennae highly attuned to the fate of faiths, Nietzsche diagnosed the prospective nadir of Christianity as the crucible of the future, and predicted that the fate of the ‘last man’ awaited those incapable of rising to the challenge it presented.

Like Aeschylus’ Prometheus, rationality is bound; its parameters determine and constrain our ideas, whether the domain be politics or ethics. The punctuation of the traditional basis of a worldview is a radically traumatic event, affecting not merely its theoretical robustness, but also the institutions which have a superstructual relation to it.

Anxiety is a motif core to all existentialist writers. The writings of the above reflect the anxiety, both intellectual and societal, of the time. Shorn of tradition, man is caught in the freefall of disbelief. Following the fall of an orientating foundation, man desperately attempts to grasp at an anchoring point from which to proceed - for Pascal it is the Wager; for Nietzsche, the Übermensch.

Concomitant with the continued erosion of traditional structures and beliefs, existentialism gained further prominence in the 20th century.

In the tradition of Dostoevsky, the Russian émigré Nikolay Berdyaev brought with him a personalist perspective nourished by the mysticism of his Orthodox faith. Catholic personalism, especially in France, flourished - offering an alternative to atheistic existentialism, marxism, and liberalism.

Famous standard bearers of this position include Emmanuel Mounier and Max Scheler - the latter, during the Catholic (he later professed Pantheism) period of his thought, influenced the theology of Pope John Paul II.

Any discussion of existentialism in the 20th century must acknowledge perhaps the most famous existentialist: Albert Camus, whose novel ‘The Stranger’ ensured the pervasiveness of his philosophy of absurdism for generations to come - the lyrics of the Cure’s ‘Killing an Arab’ pay tribute:

“I can turn and walk away, or I can fire the gun

Staring at the sky, staring at the sun

Whichever I choose, it amounts to the same

Absolutely nothingI'm alive

I'm dead

I'm the stranger

Killing an Arab”

Mentioning Camus inevitably brings us to Sartre. The frog faced standard bearer of existentialism, Sartre, was an epigone of Celine. And a turncoat too! He penned a piece on Celine in Les Temps Modernes, wherein he charged the aforesaid with being an anti-semitic collaborationist. Celine responded with a breathtakingly crude and hilarious riposte entitled ‘To the Nutcase’ – a choice quote for everyone in the audience:

“Based on the weeklies J.B.S. only sees himself in the skin of a genius. For my part and based on his texts, I am forced to see J.B.S. only in the skin of an assassin, and even more, of a fucking police informant, cursed, hideous, a pain in the ass, rumor monger, a donkey in glasses.”

And another one:

“Assassin and brilliant? We’ve seen this before...After all...Maybe that’s the case with Sartre. An assassin he is, he wants to be one, that’s understood, but brilliant? Brilliant tiny turd of my ass ? Hmmm?...That remains to be seen...yes, to be sure, that could blossom...make itself known...but J.B.S.? His embryo eyes? His mean and petty shoulders? That fat little gut... and philosopher!...that add up to a lot of things...”

Strictly speaking, Sartre was right. Celine was a collaborationist; a critic of Vichy France for being insufficiently anti-semitic. But if Celine’s war-record indicates treachery, Sartre’s actions demonstrate cowardice. Celine nods to this fact when he states:

“It seems he freed Paris on bicycle. He played around... at the Theater, the City, with the horrors of the era, the war, torture, irons, fire.”

Despite his professed anti-fascism and, later, Maoism, Sartre spent the war contriving novels, meditating on Heideggerian philosophy, and occupying a university post held previously by a Jewish professor - no wonder Camus, that stalwart of the Resistance, inspired so much envy in him.

Returning to the object of this section: if existentialism is man’s sheer horror when faced with his boundless existence, in turn catalysing the will-to-meaning, then Celine is patently not an existentialist.

Celine’s nihilism sharply contrasts with the existentialist cliché of imputing one’s own subjective meaning onto a Heraclitan universe. Contra the existentialists, he’s averse to contriving a disposition that comports with the life goals of one committed to keeping out of an insane asylum.

Celine is passive before nothingness, with a footpath-derived cig between his lips and a Gallic growl plaguing his face. His disposition is neither a concoction for the masses' sake nor a poise for disciples; he does not rely on narrative to bypass the void.

His attitude is an authentic, uniquely personal expression of being toward an ineluctable and all-consuming fact.

Phrased differently, it is the nullification of Destouches, Celine, and Bardamu, and the unveiling of the naked, authentic ego beneath. No meaning, no beyond - entropy is the rule cosmologically, and likewise, for Celine, in the human realm. So why bother?

One must look elsewhere to unveil the embryo of Celine’s beliefs; his nihilism has an analogue in his conception of the body - his pacificism and racism equally dovetail.

What is the centre that engenders and ties together the whole?