The Damaging Effect that the Television has had on Social Life

This article was originally featured on Cennétig’s Substack and is re-produced with the permission of the author.

If you wish for your work to be featured on MEON Journal, please get in touch via: meonjournal@mailfence.com

I have recently finished the book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community by Robert Putnam. The statistics mentioned in the book are shocking and would make anyone wonder if we need a new era of ludditism to reverse the trend towards societal isolation. Although it’s a study of US rather than Irish society, Ireland has also experienced the damaging effect of the television, albeit on a more delayed schedule.

Although the television has greatly facilitated the introduction of subversive foreign ideas into Irish society, the book mentioned above just focuses on the isolating effect that the television has had on society. What is noteworthy about the book is that it was written in 2000, before the internet and smartphones had any real effect on society. The trends mentioned in the book are the trends that older generations lived through, rather than the phone-addicted youth of today.

Television addiction tends to be overlooked compared to smartphone addiction, largely because it is the technology addiction of choice of the older generation. Since many from that generation hold positions of authority in media and politics, they are often quick to highlight the younger generation’s dependence on phones while ignoring their own dependence on the television.

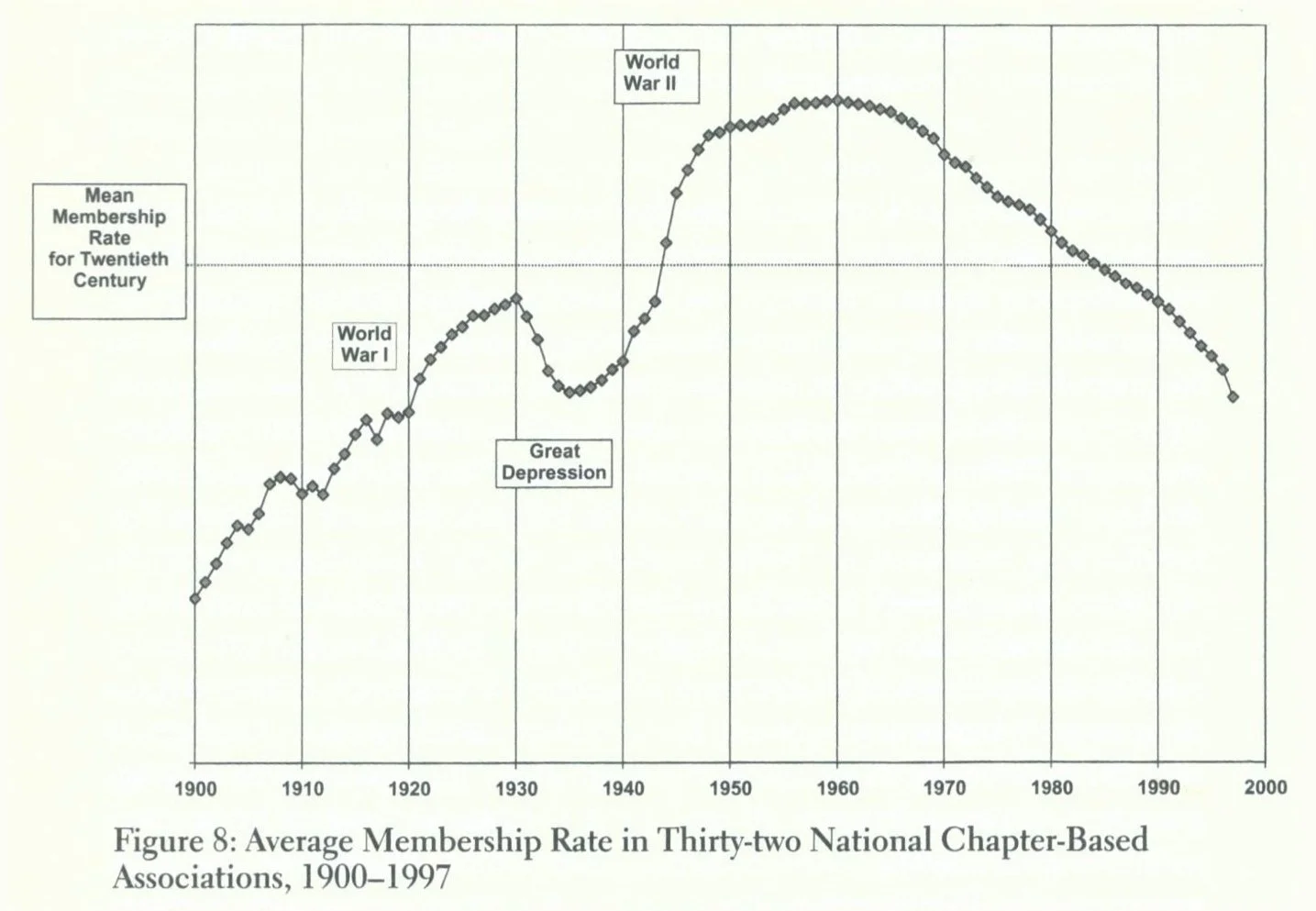

Civic engagement in US society for the first half of the 20th century was on an upward trajectory. This upward trajectory culminated in the revolutionary decade of the 1960s, which saw mass mobilisation of the population on many fronts. Around this time in the decade of the 50s, we see the rapid introduction of television into US households. In that decade, it went from 9% to 87% of households that had a television. Taking 1960 as year zero of the new television era, we can see the first decade of the television era stalling the upward trajectory of civic engagement in US society. Then the 1970s began the long decline of civic engagement that doesn’t show any sign of reversing.

As per the title of the book, ‘Bowling Alone’, the rise and decline of League Bowling is seen as a microcosm of overall trends. A rise in community engagement for the first half of the century, a plateau in the 60s and a decline from the 70s onwards. What is notable about bowling is that the years from 1980 to 1993 saw a 10% increase in the number of bowlers, while league bowlers decreased by 40%. People had begun to bowl alone.

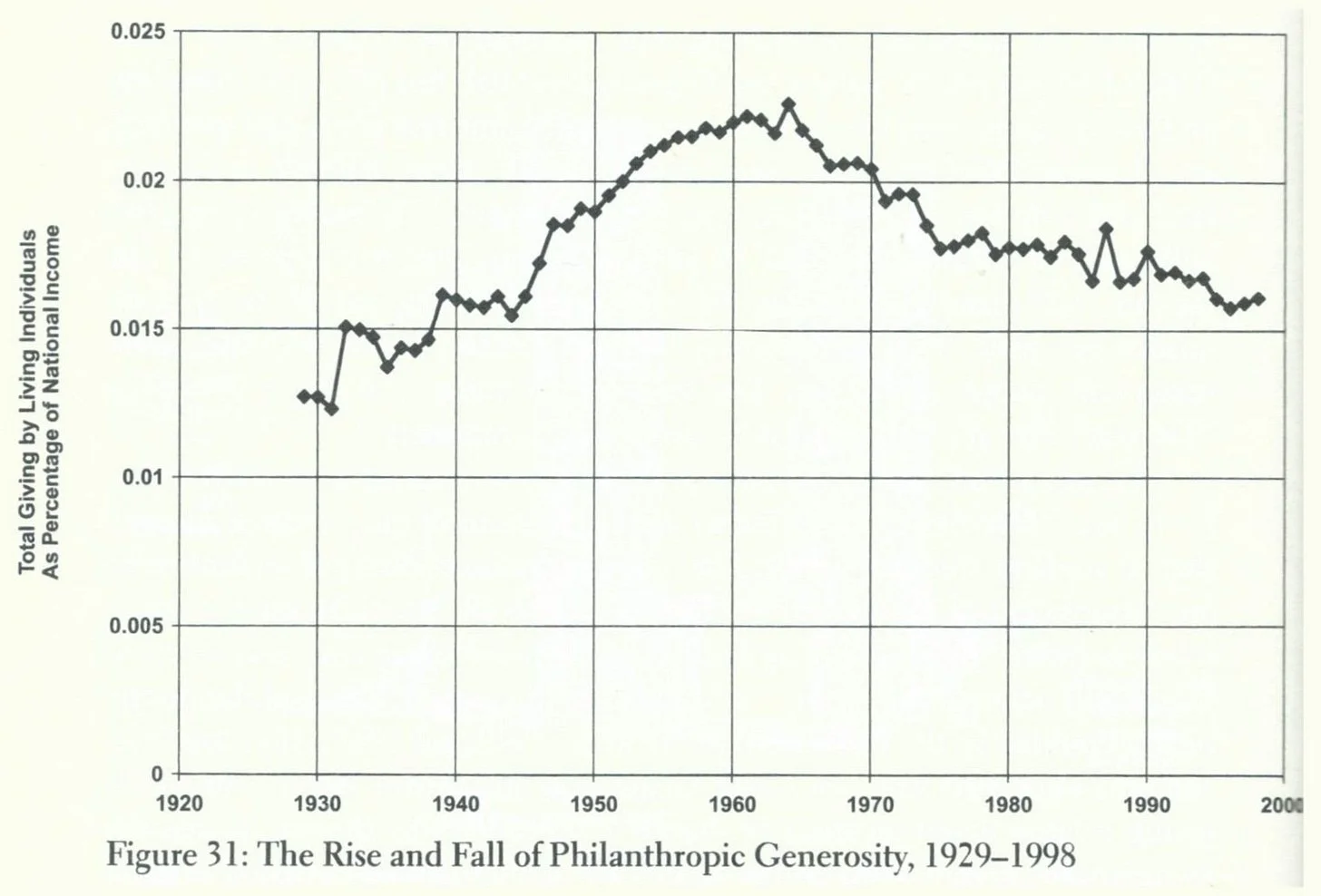

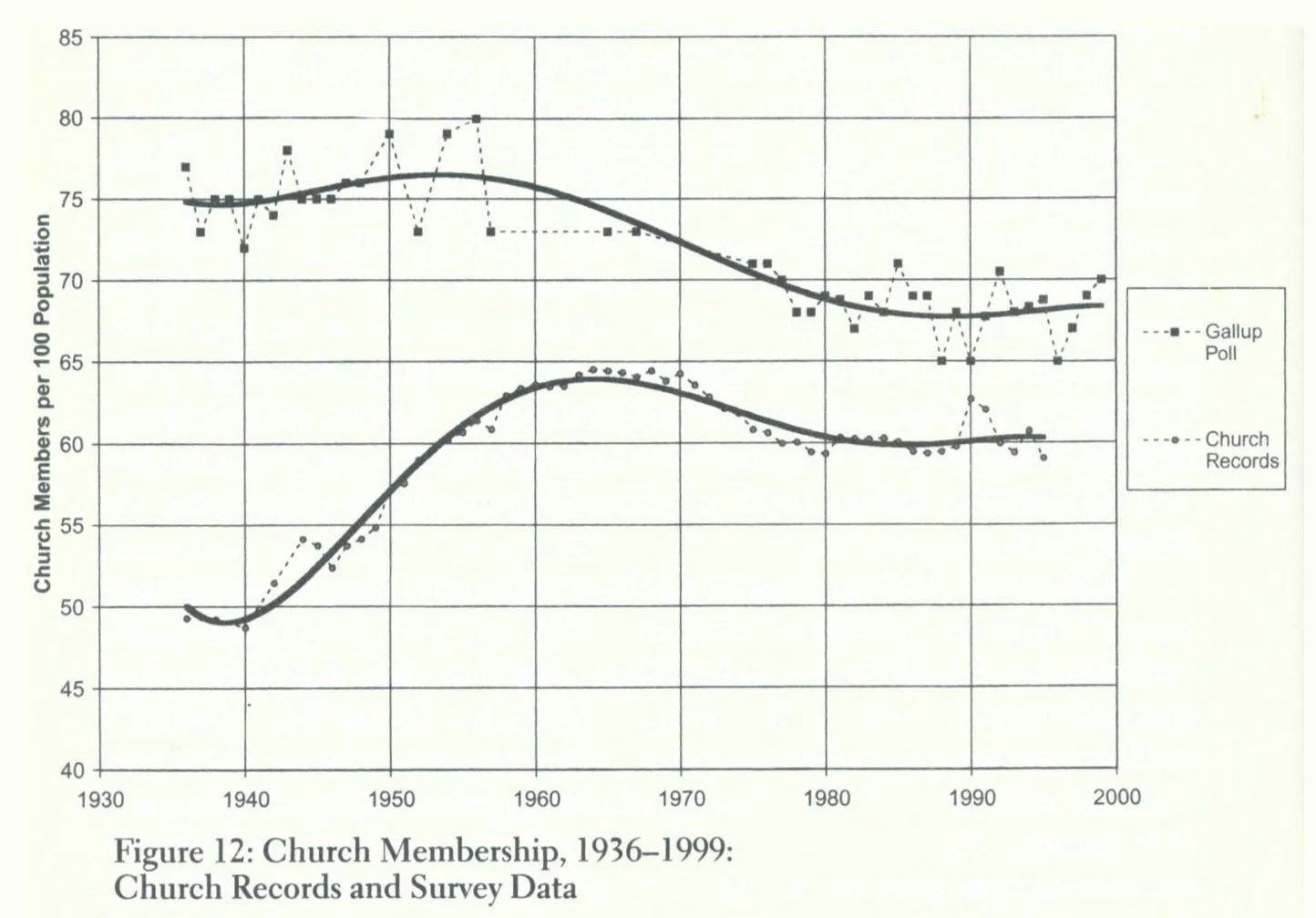

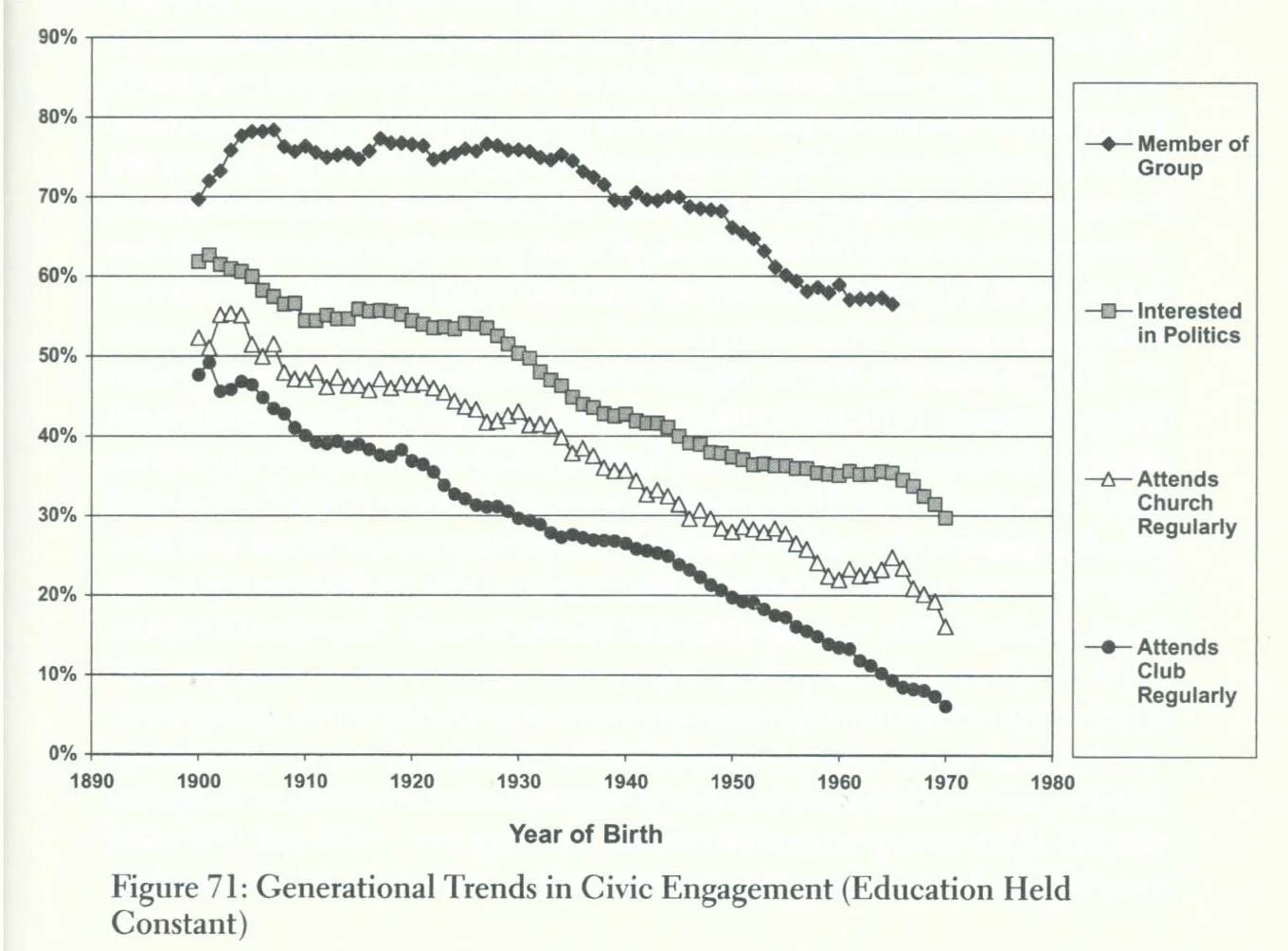

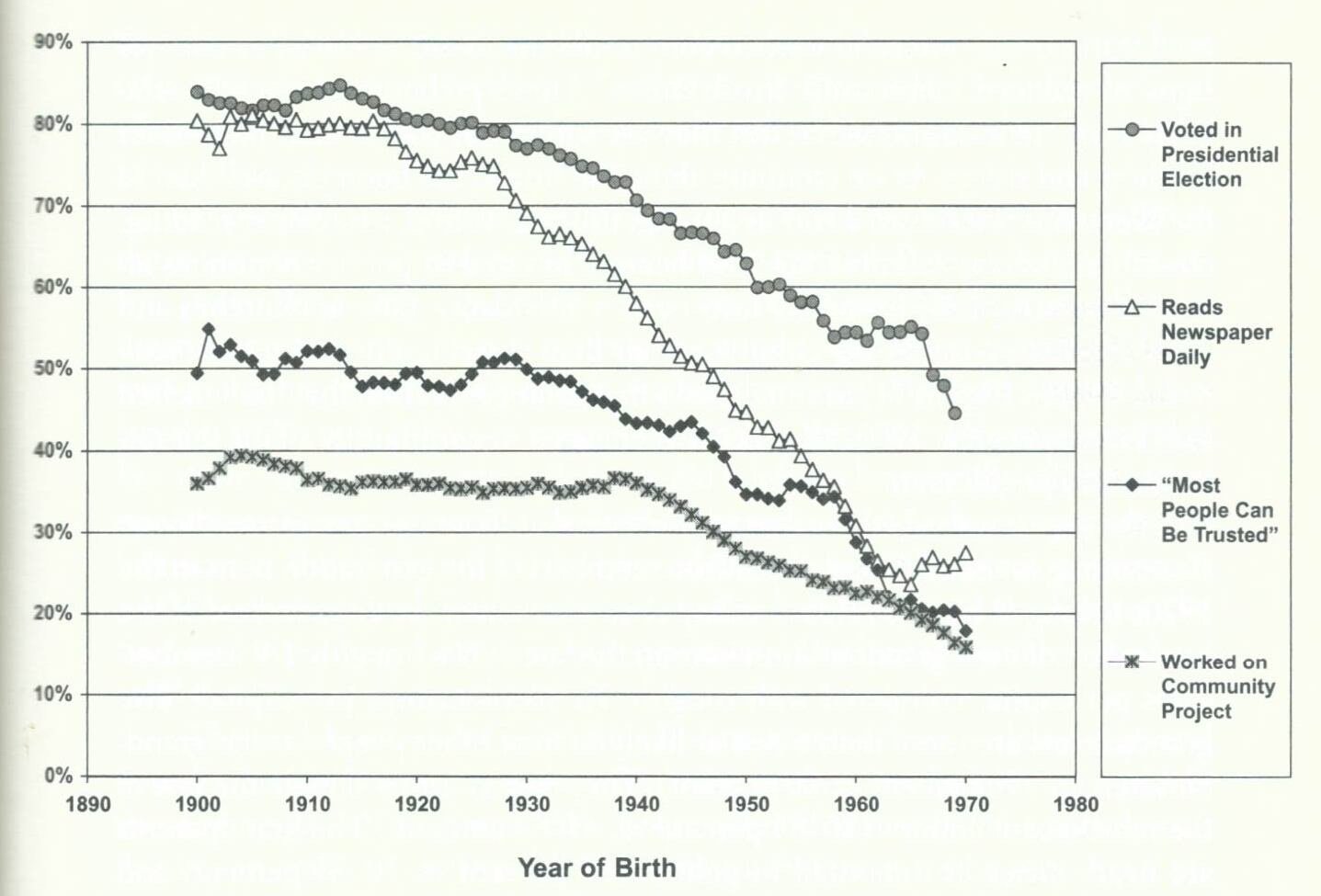

The book is full of statistics and graphs, which makes it an easy read if you are just looking to skim through the book. Mentioned in this article are only a handful of the graphs mentioned in the book. Since year zero (1960) of the new television era, barometers of civic engagement—which is a strong pillar of a socially aware and conscious society—have stalled in their upward trajectory and subsequently declined. In these three graphs below, up until the year 1960 we see an upward trend. From the 1960s onwards we either have a plateau and an eventual decline, or else just an immediate decline.

These trends mentioned above also seem to have correlated with Church membership. Up until year zero of the television being introduced into society, there was a 15% jump in religiosity in two decades. This was during a time when the US economy exploded in growth. The common belief that religiosity and economic growth are inversely correlated doesn’t seem to hold up in this instance. From the 1960s onwards, there is a gradual decline in Church membership.

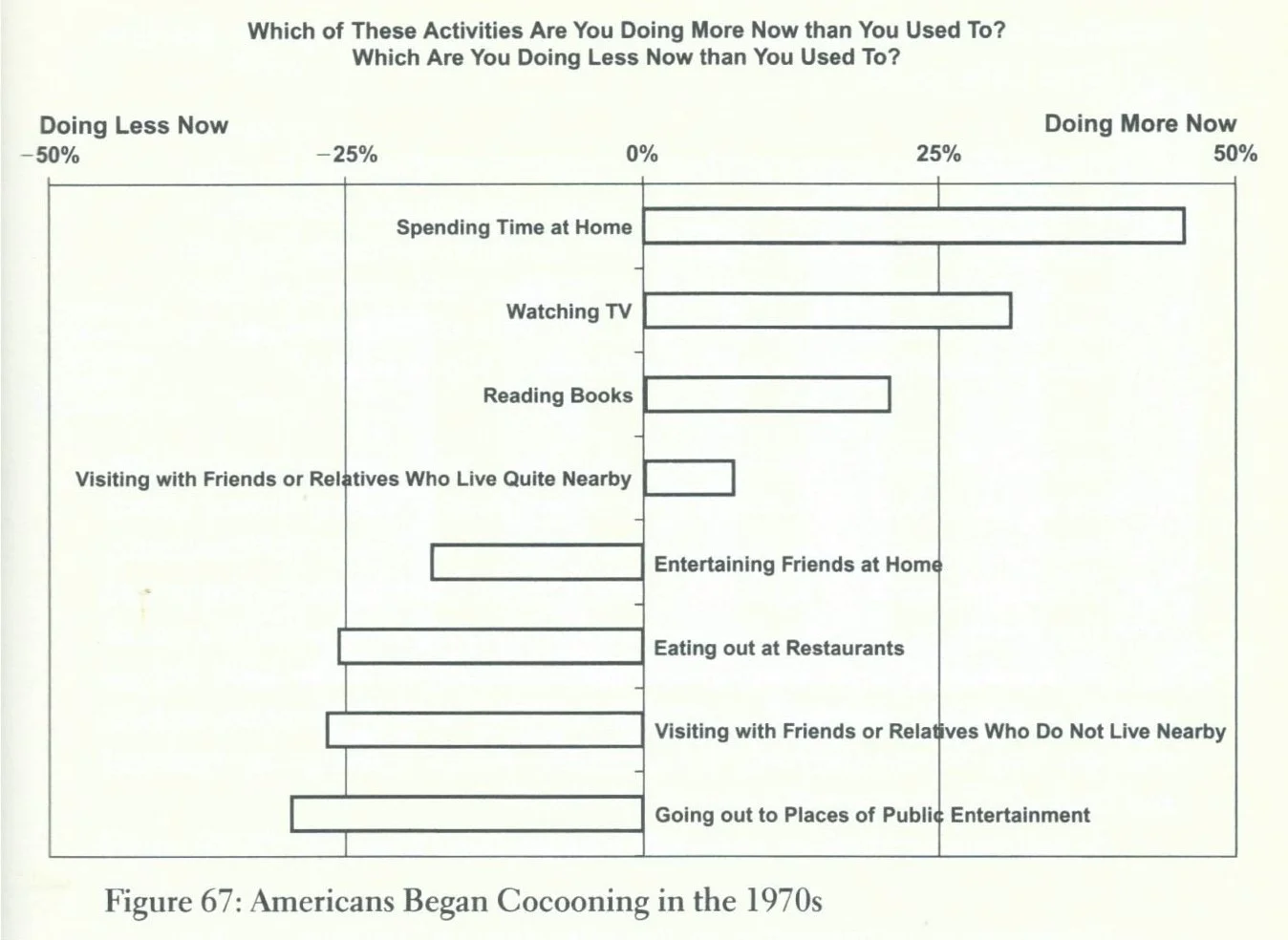

The television totally changed how people spent their free time. Before the television, people had to pick between doing a solo activity—like reading, knitting, going for a walk, etc.—or spending time with friends or family. Many people had a limit to how long they could spend on these solo activities. For the seven or so hours of leisure people had in the evening, spending it with someone else was generally seen as more enjoyable and subsequently took up a greater share of people’s leisure time.

The television suddenly turned this around and solo activities became more enjoyable. Even when television was watched with others, the dynamic of minimal communication between those watching the television and the passive consuming of whatever is shown renders it an activity not far off from other solo activities. The 1970s saw the cocooning of Yanks. As can be seen in the graph below, people used up more of their free time in solo activities at the expense of social activities.

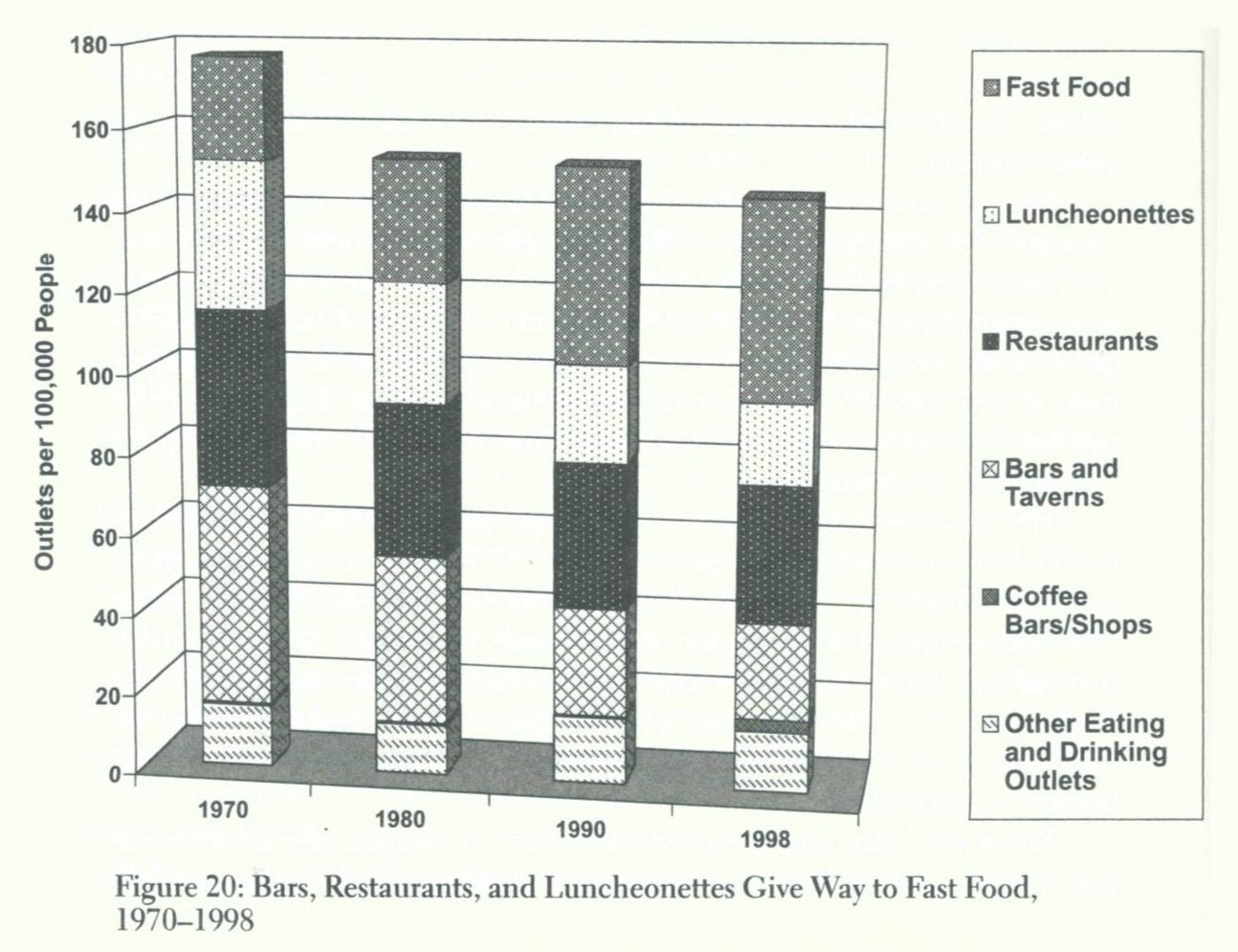

This cocooning also has an effect on our eating and drinking habits. A society that spends hours watching television everyday is a society with less social connections. Mirroring trends shown in the above graph, solo rather than social setting for eating or drinking became more common. Pubs and eating out saw a decline while an activity known for isolated eating, fast food, saw an increase. Sin begets sin. The sin of slothfulness in front of the television is a gateway to the sin of gluttony.

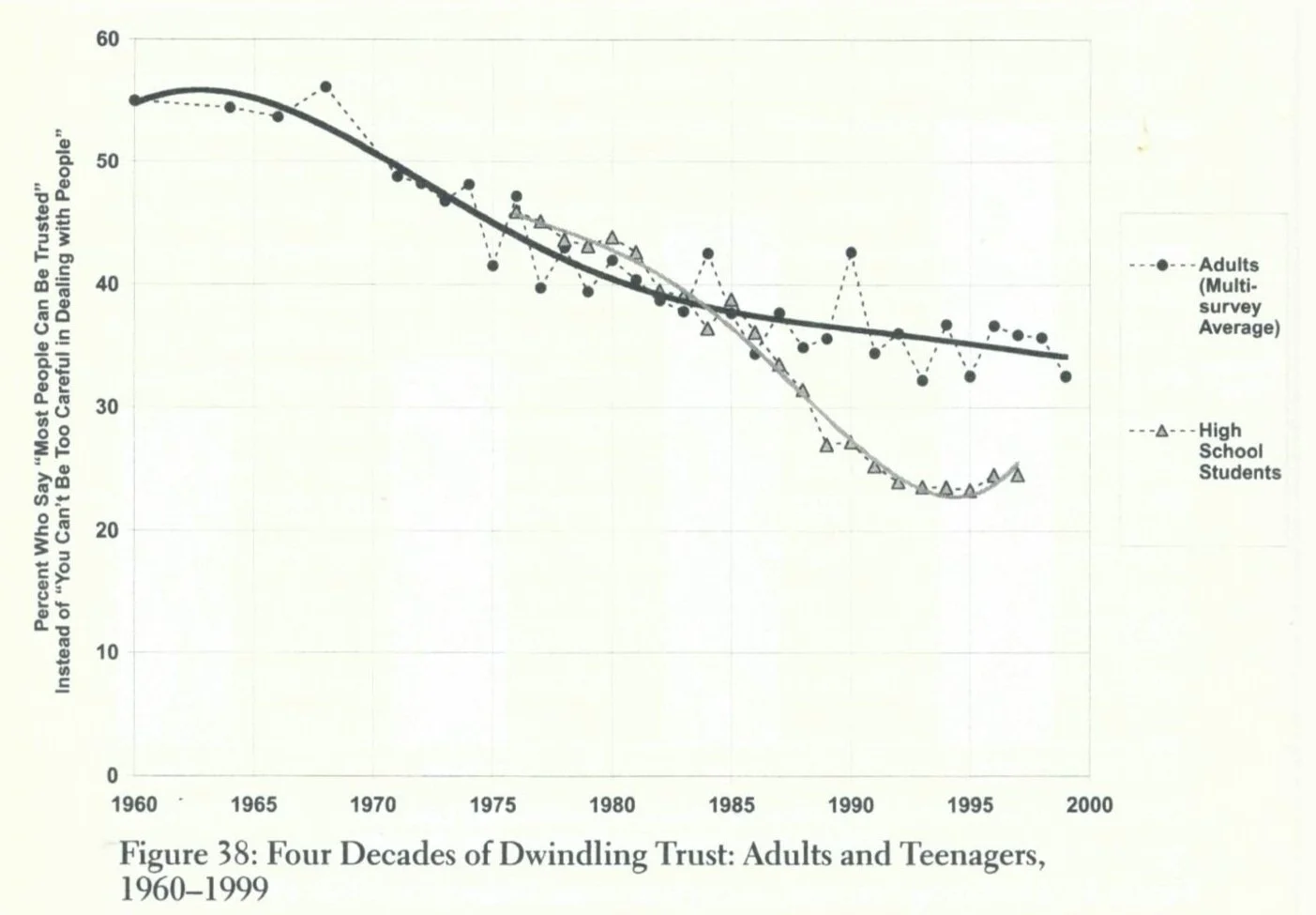

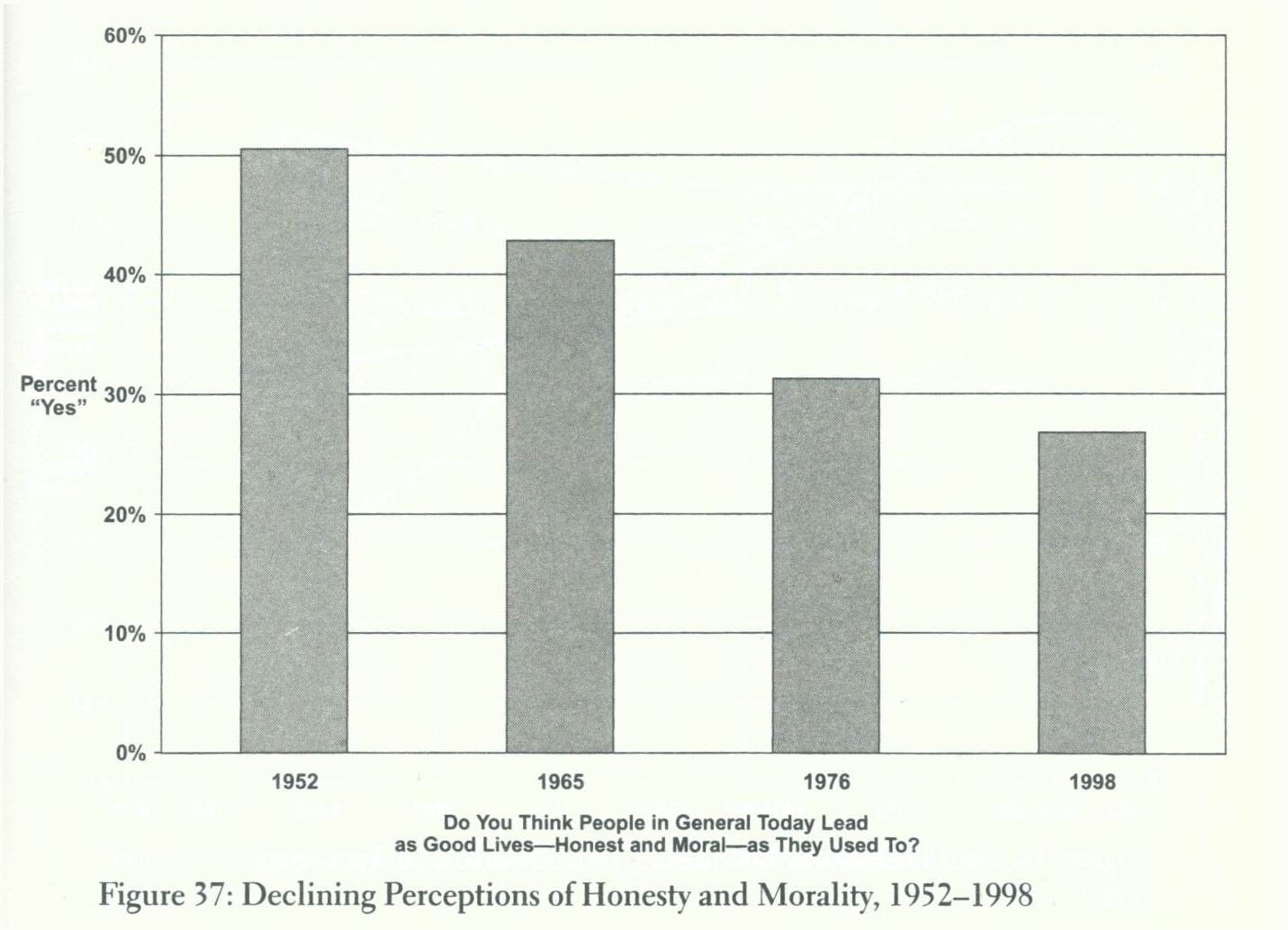

The veering towards a more asocial society leads people to lose trust in one another. If people are atomised by the television, they interact with each other less. The social connections people make with their community increases the sense of trust people have in society. If these social connections dwindle, how can people trust what they don’t personally know? The graph below begins at year zero and has the typical 1960s plateau and the subsequent multi-decade long decline.

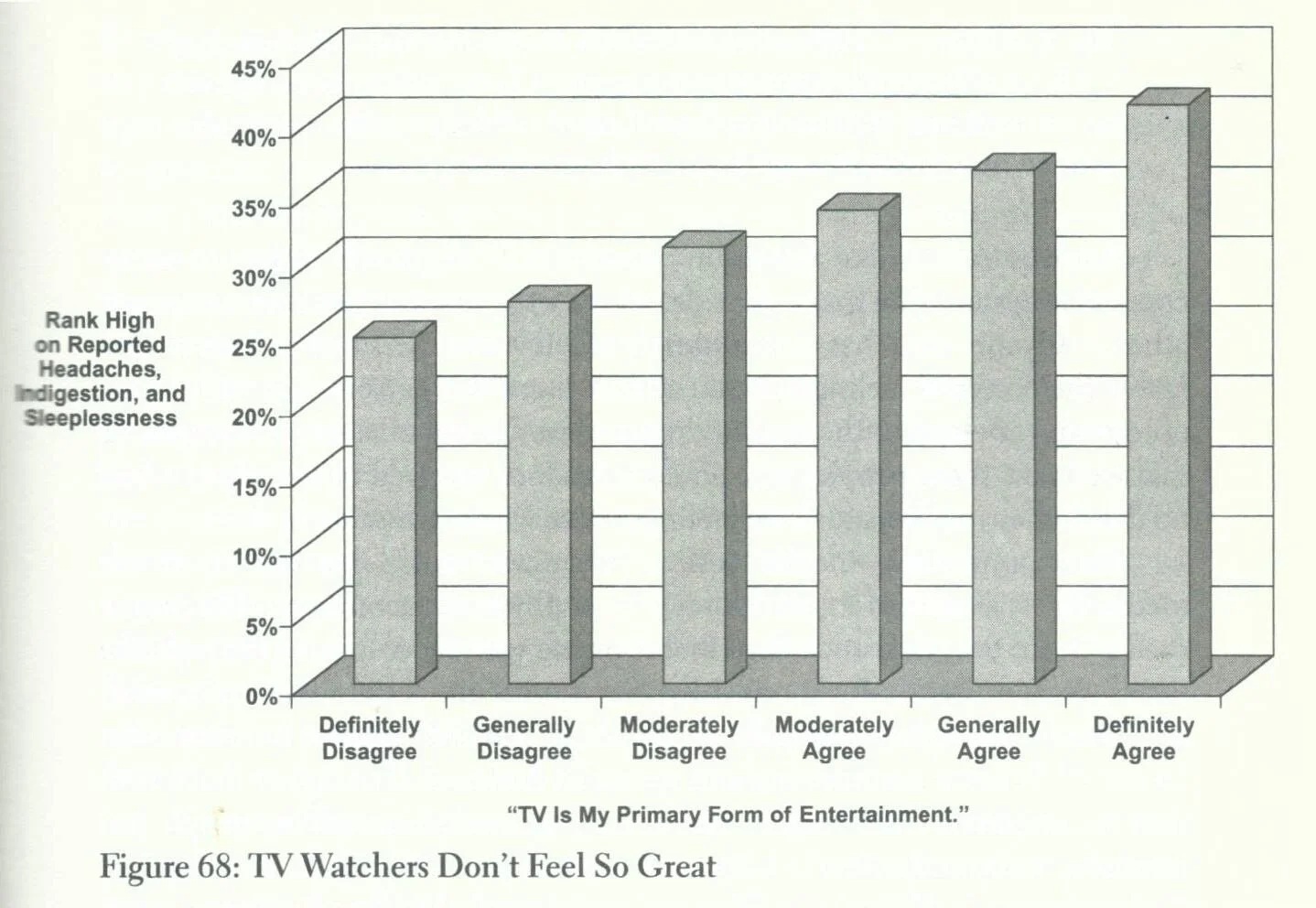

Worryingly, the correlation between the amount of television you watch and the rates of common minor illnesses like headaches, indigestion, and sleeplessness are positively correlated. These illnesses could potentially be your body’s natural response to watching too much television. Exercising, socialising, and having a sense that you are helping others are all linked to better mental health. Watching the television does the opposite of these.

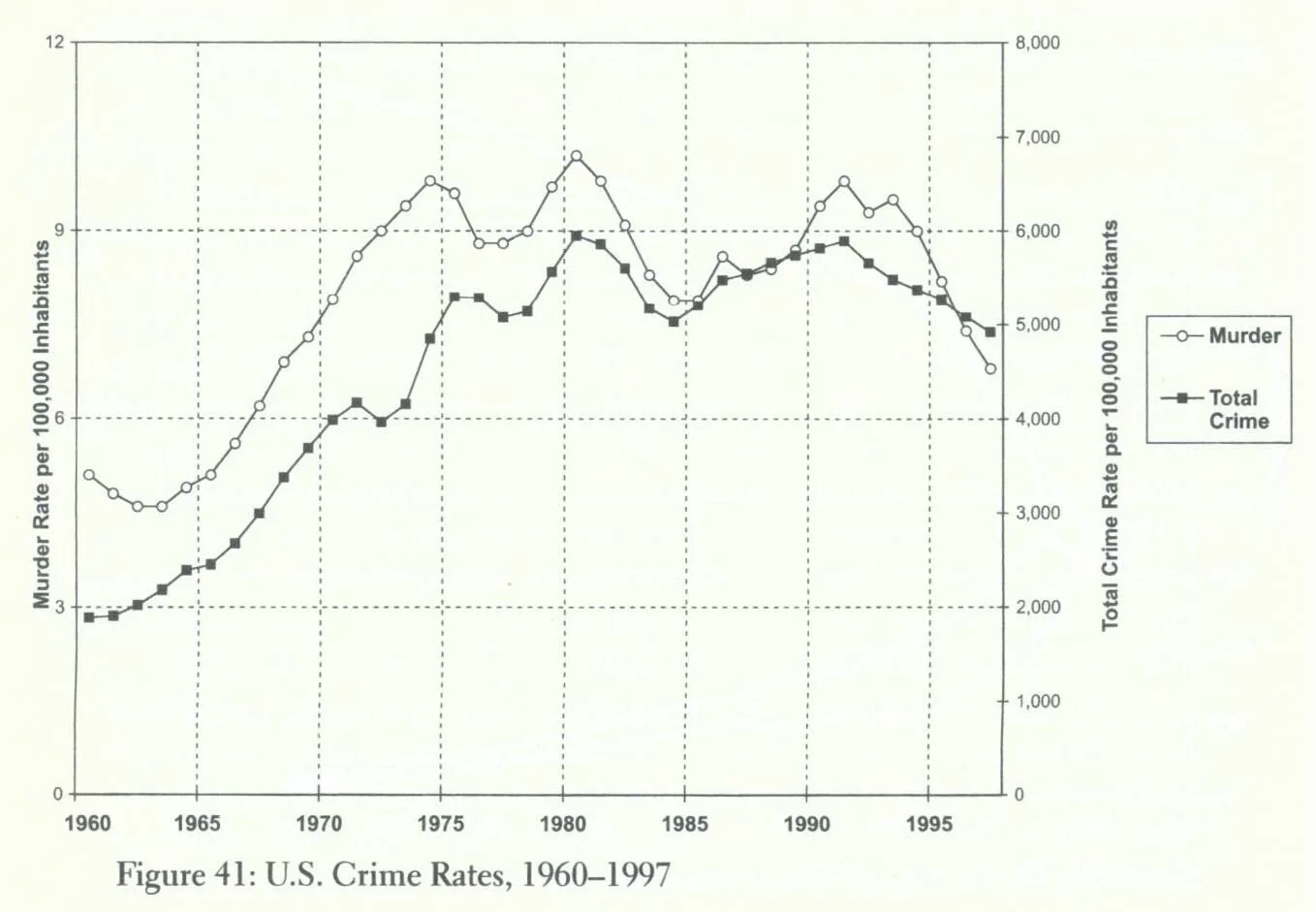

If society sees a decline in social interaction, the section of society that engages in what is today known as ‘anti-social behaviour’ increases. The positive social interactions with neighbours or other members of the community in religious or secular organisations may have integrated a section of our current criminals into the folds of society. The graph below shows a tripling of the crime rate in only two decades from 1960 to 1980.

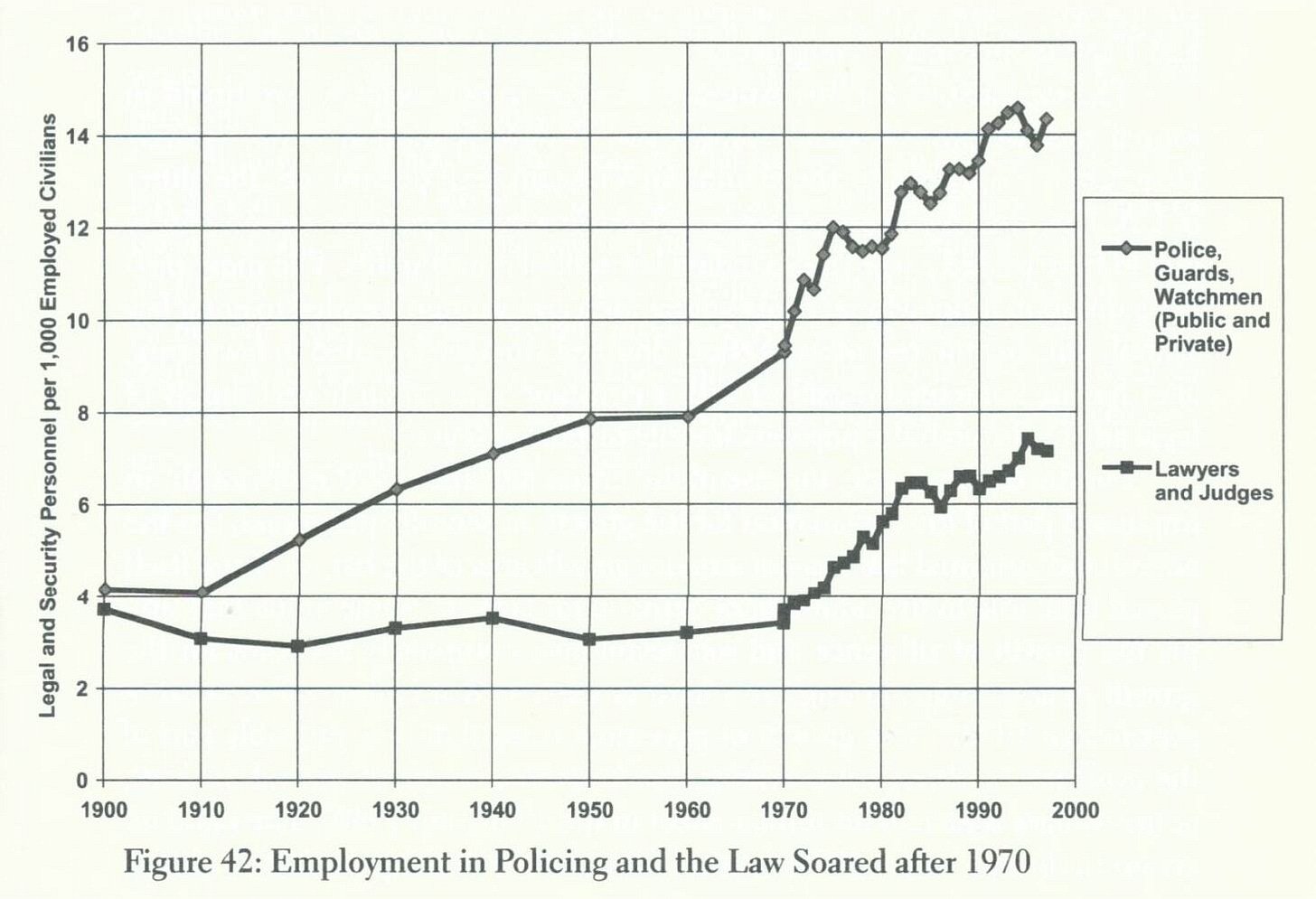

An indirect barometer of the crime rate, employment in policing and law, soared after 1970. In a moral society, the costs of policing and court proceedings are low. The increase in crime not only makes us feel less safe, especially for women and the elderly, but it is also an extra financial burden on society that in previous times would’ve been spent on other endeavours.

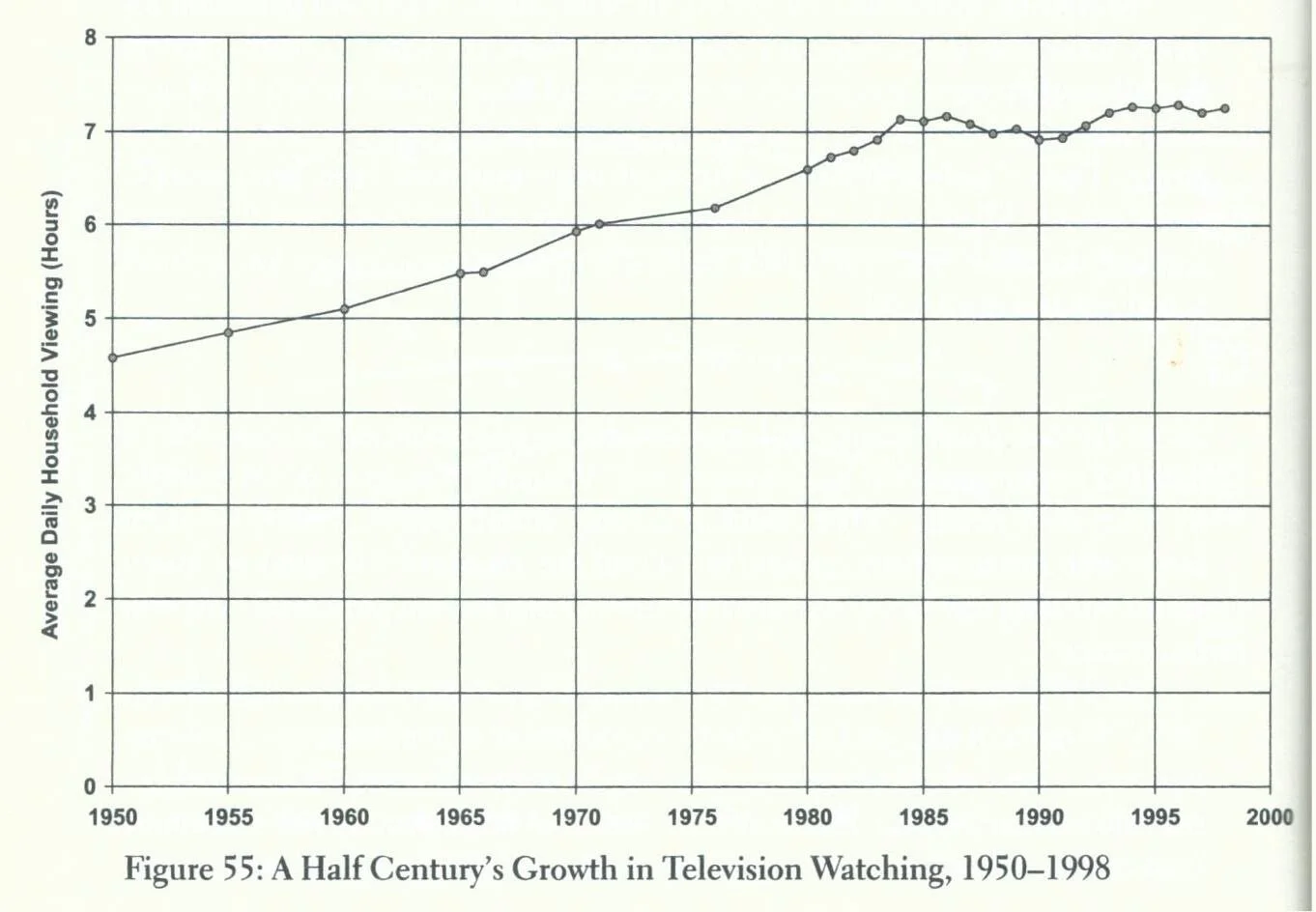

As the decades went on, television never lost its appeal. The graph below shows the steady increase in the daily household viewing. The fact that it reached above 7 hours of daily viewing is nearly unbelievable. Technology has this tendency of never becoming just a fad and fading away over time. Everything becomes more entrenched as the decades roll on. The only time we see a decline in a certain technology is when a newer more engaging one takes its place. The smartphones is that more engaging technology, which has led to the decline of the television, especially among young people.

Organised labour has also seen a decline that parallels the other indicators mentioned above. Although there is a myriad of other factors that would also play a decisive role in this decline, the 1960s plateau and the 1970s decline of union membership—a trend typical of entities affected by the television—indicates that television played some role in this decline. The television reduces people’s involvement in institutions as we have outlined above; union membership is, of course, not immune to this trend.

Spending many hours a week watching the television instead of engaging with society also saps the working and middle classes of their revolutionary potential. The television as a means of propaganda is more effective than the radio or the newspaper at shaping opinions and behaviour. It is a means also more exclusively controlled by the plutocracy, compared to the more grassroots ownership of the radio and the newspaper. Therefore it would not be surprising if the working and middle classes began to become disengaged with promoting their class interests after the introduction of the television.

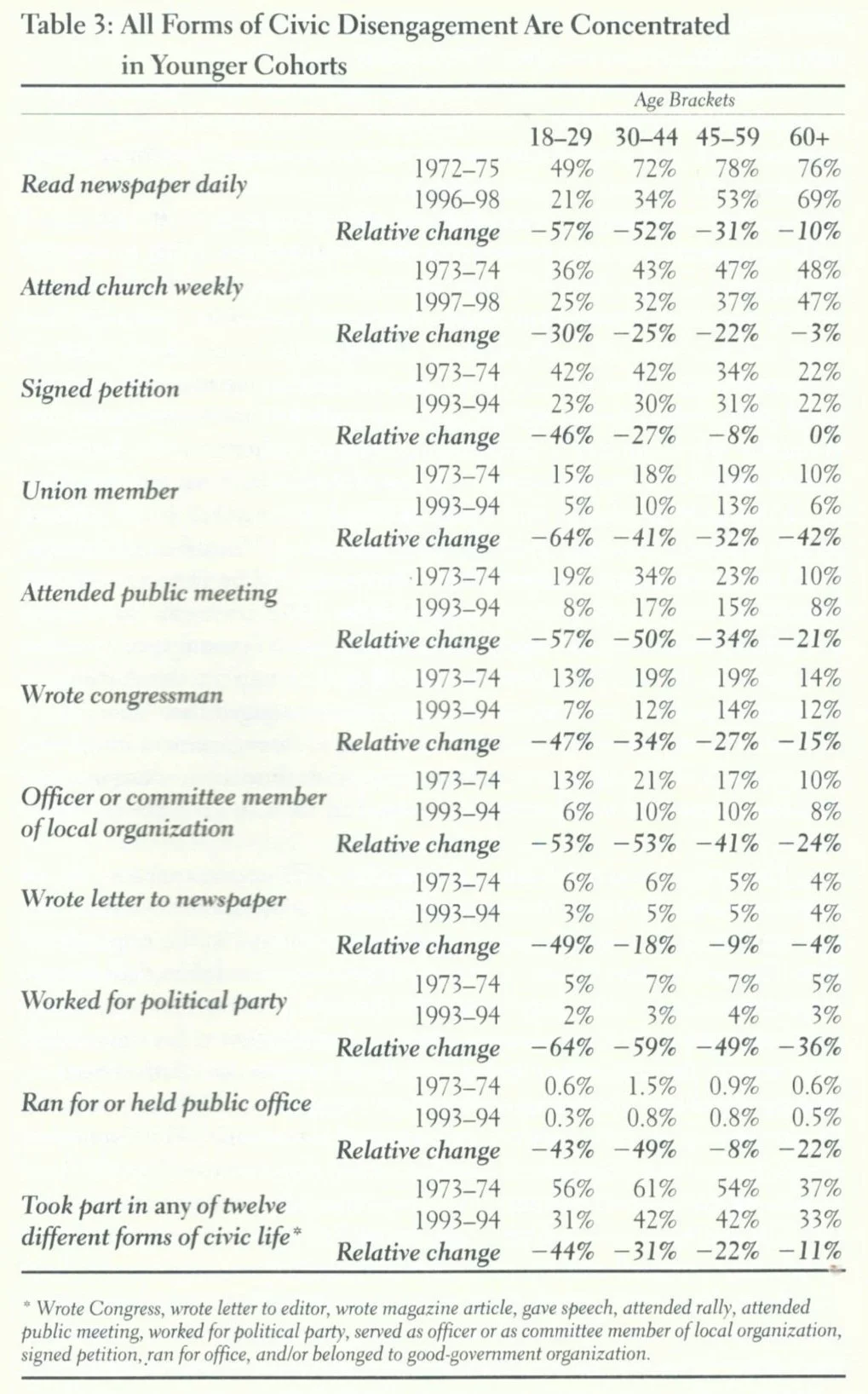

The trend of social isolation caused by the television is also strongly rooted in particular generations where the television has been present for a greater portion of their lives. The table below compares how civically engaged different age groups were in the years 1972-75 and 1996-98. This table is structured in a way to account for the effect that the natural life cycle has on civic engagement by controlling for age.

All age groups experienced a decline in civic engagement, but the younger the age group, the bigger the decline. This can be explained by the older generation living a good portion of their lives—especially the developmental stages of their teens and twenties—without the television. The 60+ generation would have been born before 1915 in the 1972-75 time bracket and born before 1938 in the 1996-98 time bracket. Both groups would have experienced a life before the television. Civic engagement—using the last summarising statistic—declined by 11%. The television had an effect on civic engagement, but not by much.

The 18-29 age group in comparison saw a 44% decline between 1972-75 and 1996-98. The 1972-75 group would’ve been born between the years 1943 and 1957. They may have had early memories of life without a television in the household and their developmental years would’ve been in a society still adjusting to the new television age. The 1996-98 group, in comparison, would’ve only known a world where television was omnipresent in every household and was fully integrated into the fabric of society.

The three graphs below further illustrate the generational divide between younger and older generations. All graphs point in one direction, the younger television generations are less civically engaged, more socially isolated, and less trustful of others.

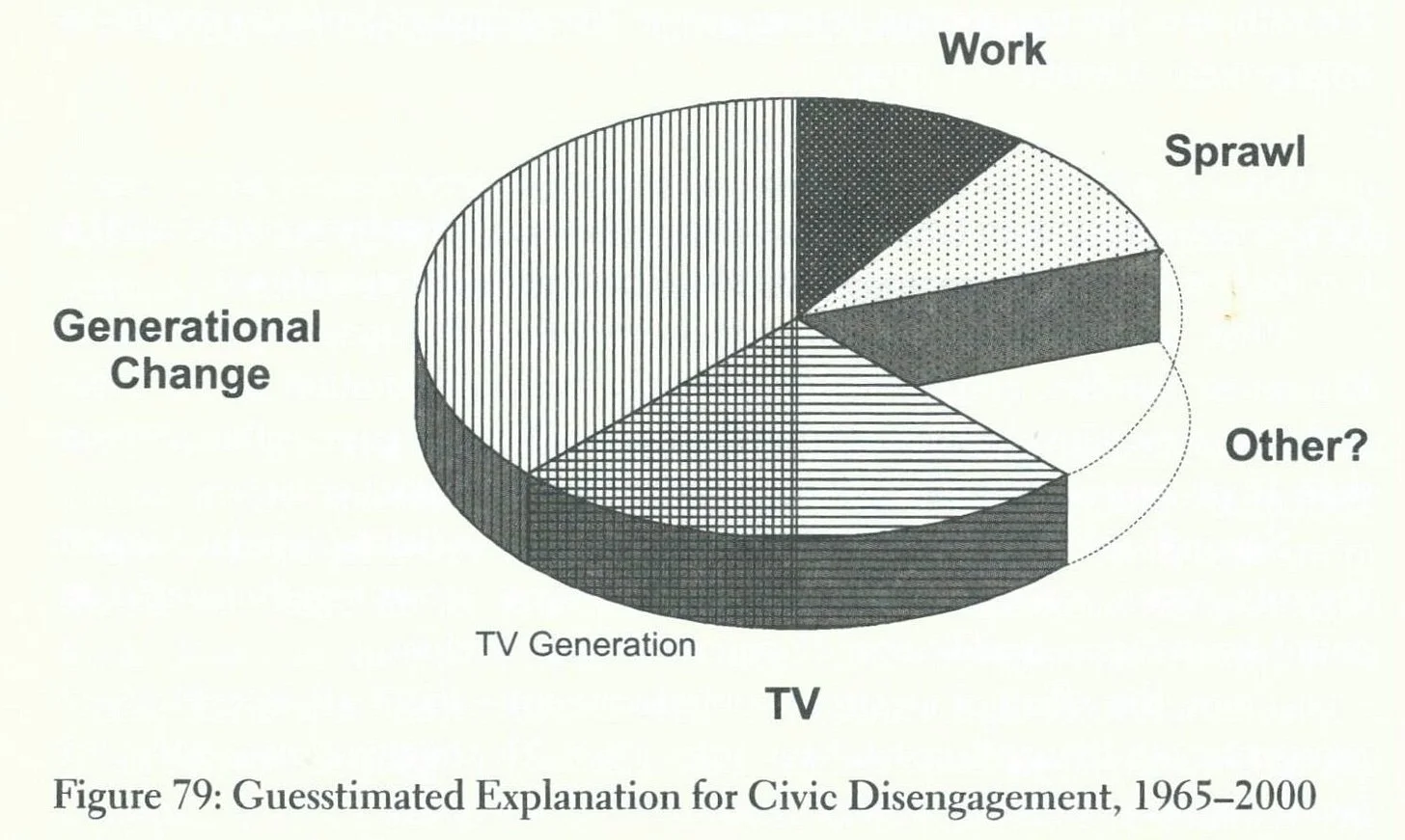

The book this article is based on—Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community—isn’t primarily about the television; it is about the causes behind the decline of civic engagement in the second half of the twentieth century in the USA. As can be seen from in the pie chart below, the author also attributes other factors like the alienating effect that the growth of the suburbs had and the increase of mothers into the workforce to this decline in civic engagement.

The book concludes with an explanation of civic disengagement, but the real question should be the causes of this disengagement. This would make the generational change section unsuitable and leave us with the three causes of the television, work, and (urban) sprawl. I would argue that the television is the dominant cause of the decline of social life in society, while the other two causes are amplifiers of overall trends.

If the television is to blame for the massive rise in societal isolation, why do we tolerate this cancerous technology in our society? Advocating for the banning of the television or for the strict regulation of its output to solely educational and nationally produced material would today be seen as unthinkable. Advocating for fascism would probably be seen as more socially acceptable. We as humans have created the television, but we are being ruled by it. The television now has agency over humanity, rather than the other way around. Why do we tolerate this state of affairs?